The following article explores "Frozen Engineering," a cutting-edge domain of manufacturing that uses ice not just as a final product, but as a sophisticated, ephemeral engineering tool.

**

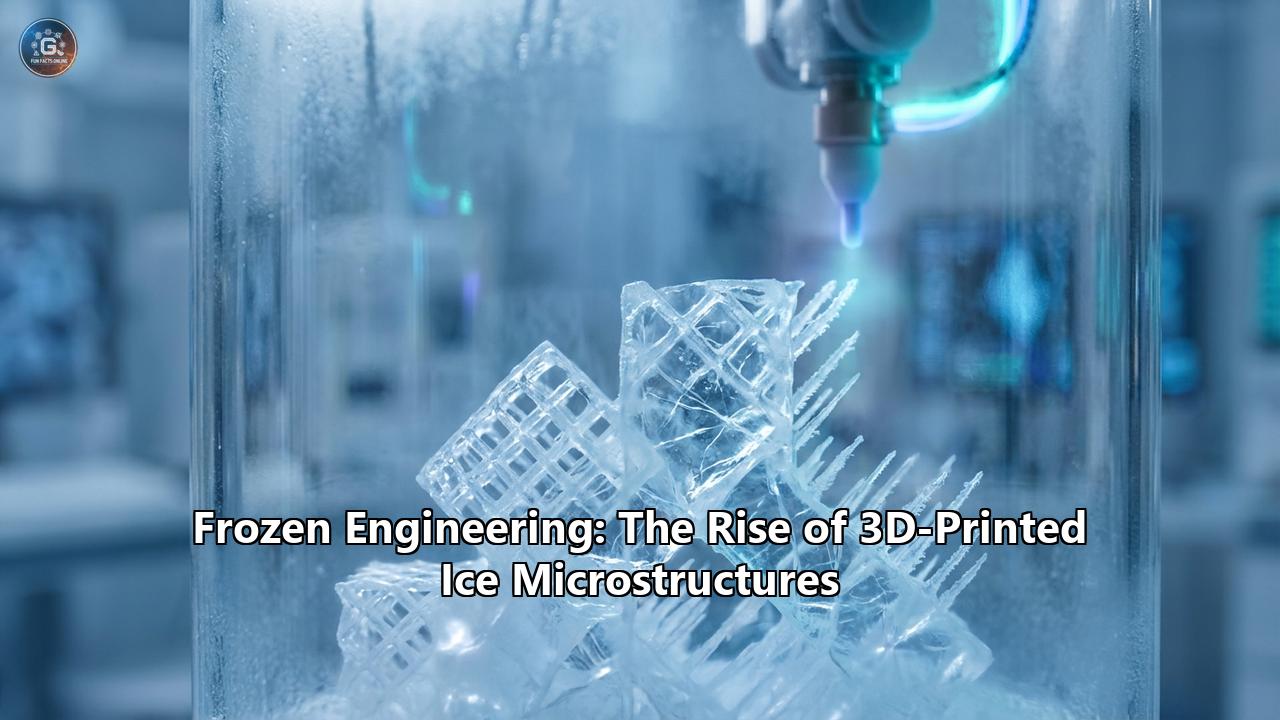

Frozen Engineering: The Rise of 3D-Printed Ice Microstructures

Introduction: The Ephemeral Architect

In the annals of materials science, ice has traditionally been viewed as an adversary—a brittle, transient nuisance that cracks pipes, erodes roads, and freezes crops. It is the material engineers usually design against. Yet, a quiet revolution is underway in laboratories from Pittsburgh to Beijing, overturning this millennia-old bias. By harnessing the precise phase transitions of water, scientists are forging a new discipline: Frozen Engineering.

At the heart of this revolution is the ability to 3D-print ice with microscopic precision. This is not the crude stacking of ice blocks for winter festivals; it is the manipulation of water droplets picoliter by picoliter, freezing them into impossible geometries that serve as sacrificial templates for the world’s most complex machines: artificial organs, microfluidic chips, and soft robots.

Why ice? The answer lies in its paradox. Ice is solid enough to hold a shape but fragile enough to vanish without a trace. In a world drowning in plastic waste and toxic solvents, water is the ultimate "green" manufacturing agent. It enters the process as a builder and leaves as harmless vapor, bequeathing intricate voids and channels that no mechanical drill could ever carve.

This article delves into the depths of Frozen Engineering, exploring the physics that allows water to defy gravity, the medical breakthroughs enabled by melting veins, and the futuristic visions of ice cities on Mars.

Part I: The Physics of Frozen Fabrication

To understand how one prints with ice, one must first abandon the intuition of the ice cube tray. Industrial freezing is a chaotic, bulk process. Frozen Engineering, by contrast, is a ballet of thermodynamics played out on the scale of microns.

1.1 The Micro-Meniscus and the Taylor Cone

The fundamental challenge of printing ice is controlling the liquid-to-solid transition instantly. If the water freezes too fast, it clogs the nozzle; too slow, and the structure collapses into a puddle.

Research pioneered at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) has cracked this code using a "Drop-on-Demand" (DoD) approach. The process relies on a piezoelectric nozzle that ejects water droplets as small as 50 microns—thinner than a human hair. These droplets land on a build platform cooled to -35°C.

But the magic happens in the frequency. By modulating the rate at which droplets are fired, engineers can control the "liquid cap"—a tiny reservoir of unfrozen water that sits atop the growing ice pillar.

- Low Frequency: Each droplet freezes completely before the next arrives. This creates a layered, "bamboo-like" structure, strong but with rough edges.

- High Frequency: A stable liquid meniscus is maintained at the tip. The freezing front chases this liquid cap upward. This allows for smooth, continuous printing, enabling the fabrication of overhangs, helices, and branching structures that defy gravity without support material.

For even higher resolution, we turn to Electrohydrodynamic (EHD) Jetting, a technique often utilized in "Ice Lithography" (iEBL). Here, a high-voltage electric field pulls the water from the nozzle. The liquid forms a Taylor Cone—a conical shape that tapers to a microscopic point—ejecting a jet far smaller than the nozzle itself. This allows for nanoscale precision, writing ice patterns invisible to the naked eye.

1.2 Nucleation and Recalescence

The physics of the droplet’s impact is violent and beautiful. When a supercooled water droplet hits the frozen substrate, two things happen:

- Nucleation: The instant the droplet touches the ice crystal below, the crystal lattice propagates into the liquid. This is the "seed" of the freeze.

- Recalescence: Freezing releases latent heat. This sudden burst of energy warms the droplet back up to 0°C, temporarily stalling the freeze.

In Frozen Engineering, the substrate acts as a massive heat sink, sucking this latent heat away instantly. The mastery of this heat transfer equation allows engineers to print "out of plane"—creating ice branches that grow sideways at 80-degree angles, held up only by the strength of their own crystalline lattice.

Part II: The Technologies of Ice

Frozen Engineering is not a monolith; it is a spectrum of technologies ranging from the desktop-scale to the electron-microscope scale.

2.1 3D-ICE: The Meso-Scale Workhorse

The 3D-ICE (Freeform 3D Ice Printing) platform, developed extensively by the LeDuc and Ozdoganlar labs at CMU, is the standard-bearer for this field.

- Mechanism: Inkjet-based deposition on a multi-axis stage.

- Material: Heavy water (Deuterium oxide, D₂O) is sometimes used because it has a higher freezing point and different viscosity than regular water, offering smoother prints.

- Capability: It can print complex "trees" of ice, octopus-like shapes, and lattice scaffolds.

- Primary Use: Creating sacrificial templates for tissue engineering (see Part III).

2.2 iEBL: Ice Electron Beam Lithography

While 3D-ICE builds upwards, iEBL carves downwards. Developed by researchers at Zhejiang University and Peking University, this technique is a subtractive method for the nano-world.

- The Process: A silicon wafer is cooled to cryogenic temperatures (-130°C) inside a vacuum chamber. Water vapor is introduced, condensing into a perfectly smooth, nanometer-thin sheet of amorphous ice.

- The Tool: An electron beam, usually used to see things, is turned up to "write" on the ice. The electrons sublime the ice instantly, carving trenches and patterns.

- The Advantage: Traditional lithography requires coating chips with toxic photoresists (polymers), baking them, exposing them, and washing them with harsh chemicals. iEBL uses only water. Once the pattern is transferred (e.g., by depositing metal into the ice trenches), the ice simply melts away. It is the cleanest manufacturing process on Earth.

2.3 Cryogenic Machining & Frozen Sand Casting

Scaling up, we enter the industrial realm. "Frozen Engineering" also encompasses Cryogenic Machining.

- The Problem: Machining soft materials like rubber or silicone is a nightmare; they squish and tear rather than cut.

- The Frozen Solution: By blasting the material with liquid nitrogen or freezing it into a block of ice, soft elastomers become hard as stone. They can then be machined with diamond-sharp precision. Once thawed, they return to their rubbery state, retaining the complex geometries machined into them.

Similarly, Frozen Sand Casting is disrupting the foundry industry. Instead of using chemical binders (glues) to hold sand molds together for metal casting, engineers mix sand with water and freeze it. The molten metal is poured into the frozen mold. The heat of the metal melts the ice, but not before the metal skin solidifies. The result? A cast metal part and a pile of damp sand—zero toxic fumes, zero chemical waste.

Part III: The Killer Application – Artificial Organs

The "Holy Grail" of tissue engineering is the ability to grow functional human organs. We can already grow liver cells and heart cells in a dish. The problem is keeping them alive.

3.1 The Vascularization Paradox

Living tissue needs oxygen. In the human body, no cell is more than a few hairs' width away from a capillary. If you stack cells into a block thicker than a sheet of paper, the cells in the middle suffocate and die. To build a heart, you need a plumbing system—a vascular network—that is dense, complex, and hierarchical, branching from large arteries down to microscopic capillaries.

3D printing plastic blood vessels doesn't work well; the plastic is permanent and blocks cell interaction. This is where Sacrificial Ice Templating changes everything.

3.2 The "Inside-Out" Printing Method

The workflow developed by bio-engineers using 3D-ICE is a stroke of genius:

- Print the Blood: First, they 3D-print the negative space. They print the tree-like structure of the blood vessels using ice.

- Cast the Tissue: This ice tree is dipped into a gel containing human cells and structural proteins (like collagen or gelatin).

- The Great Melt: The gel is cross-linked (cured) with UV light to make it solid. Then, the temperature is raised. The ice tree inside turns to water and flows out.

- The Result: A block of living tissue riddled with smooth, interconnected channels that perfectly mimic blood vessels.

Because ice melts into water—the very substance life depends on—there is no toxic residue. Engineers can immediately pump nutrient-rich fluid through these channels, keeping the interior cells alive. This method has successfully created blocks of tissue with functioning endothelial linings, bringing us one step closer to 3D-printed kidneys and hearts.

Part IV: Beyond Biology – Microfluidics and Soft Robotics

The utility of frozen engineering extends well beyond the body.

4.1 Microfluidics: The Lab on a Chip

Microfluidics involves manipulating fluids in channels smaller than a human hair. These "Labs on a Chip" are used for everything from DNA analysis to detecting diseases. Manufacturing them typically requires expensive cleanrooms and complex lithography.

With ice printing, a researcher can simply print the channel design in ice, pour a liquid polymer (like PDMS) over it, cure it, and let the ice melt. It democratizes high-tech manufacturing, allowing any lab with an ice printer to prototype complex fluidic devices in hours rather than weeks.

4.2 Soft Robotics

Soft robots are machines made of squishy materials that can squeeze into tight spaces or handle delicate objects (like fruit or human patients) without harming them. These robots are powered by pneumatic networks—internal channels of air or fluid that inflate to make the robot bend.

Creating these internal air bladders is difficult. You can't drill a curved hole inside a block of rubber. But you can* print a curved spiral of ice, pour liquid rubber around it, and let it cure. As the ice melts and drains away, it leaves behind a perfect, spiral air chamber. When pressurized, this chamber acts as an actuator, causing the robotic limb to curl or grip.

Part V: The Green Revolution of "Phase-Change Manufacturing"

We are living in the Polymer Age, but the environmental bill is coming due. 3D printing, despite its reputation for efficiency, relies heavily on plastics (PLA, ABS) and resin baths that generate hazardous waste.

Ice is the ultimate sustainable material.- Recyclability: The "waste" material from ice printing is water. It can be collected, filtered, and re-printed infinitely.

- Energy Efficiency: While freezing requires energy, it often requires less than the high heat needed to melt metals or thermoplastics. Furthermore, sublimation (turning ice directly to vapor) allows for the gentle removal of support structures without harsh chemical solvents.

- Biocompatibility: In medical applications, replacing toxic photo-initiators and solvents with water eliminates the risk of rejecting the implant due to chemical contamination.

Part VI: Future Horizons – From Quantum Cooling to Mars

As we look to the next decade, Frozen Engineering is set to expand into extreme environments.

6.1 Quantum Computing and Cooling

High-performance electronics and quantum computers generate immense heat and require complex cooling solutions. 3D-printed ice templates can create "micro-vascular" cooling jackets for computer chips. These internal channels, woven directly inside the chip packaging, allow coolant to flow within microns of the hot transistors, offering cooling efficiencies impossible with traditional external heat sinks.

6.2 ISRU: In-Situ Resource Utilization

The ultimate frontier for Frozen Engineering is not on Earth. NASA and private space companies are heavily investing in In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). Carrying building materials to Mars is prohibitively expensive. But Mars has ice.

- Project Mars Ice House: A winner of NASA’s Centennial Challenge, this concept proposes 3D-printing habitats on Mars using local water ice.

- The Physics of Mars: On Mars, the low atmospheric pressure means ice sublimes directly to vapor. However, with the right pressure and temperature control, a robotic printer could harvest Martian permafrost, melt it, and re-freeze it into translucent, radiation-shielding domes.

Ice is an excellent shield against cosmic radiation. A 5-centimeter thick shell of ice can block dangerous solar particles while letting in visible light, solving the "cave dweller" problem of living in dark underground bunkers. Frozen Engineering could literally be the technology that houses the first human colonists on other worlds.

Conclusion: The Solid-Liquid Future

Frozen Engineering challenges our perception of permanence. We are accustomed to building with steel and stone—materials that last for centuries. But nature builds with flow. A river carves a canyon; blood flows through transient vessels.

By mastering the fleeting state of ice, engineers are learning to build like nature. They are creating structures that are defined not by what remains, but by the spaces they leave behind. From the microscopic capillaries of a lab-grown liver to the shimmering ice domes of a Martian colony, the future of engineering is cold, clear, and melting.

The rise of 3D-printed ice microstructures is more than a novelty; it is a shift toward a manufacturing paradigm that is cleaner, more organic, and infinitely adaptable. In the end, the most powerful tool in the engineer's kit might just be a drop of water, frozen in time.

Reference:

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264427015_Super-Resolution_Electrohydrodynamic_EHD_3D_Printing_of_Micro-Structures_Using_Phase-Change_Inks

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379880884_Advancing_sustainable_casting_through_cryogenic_gradient_forming_of_frozen_sand_molds_Design_error_control_and_experimental_validation

- https://www.georgetownspace.org/contentmaster/making-a-home-on-the-moon-and-mars-with-isru-technology

- https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Madhu-Thangavelu/publication/347508732_ISRU-BASED_ROBOTIC_CONSTRUCTION_TECHNOLOGIES_FOR_LUNAR_AND_MARTIAN_INFRASTRUCTURES_NIAC_Phase_II_Final_Report/links/5fdf0b51a6fdccdcb8e60ff1/ISRU-BASED-ROBOTIC-CONSTRUCTION-TECHNOLOGIES-FOR-LUNAR-AND-MARTIAN-INFRASTRUCTURES-NIAC-Phase-II-Final-Report.pdf

- https://worldarchitecture.org/articles/cehhm/mars-ice-house-uses-inventive-materials-and-3d-printing-techniques-to-build-a-new-habitat-on-mars.html