The wind howls across the high plains of what is now Converse County, Wyoming, carrying with it the biting chill of the waning Ice Age. It is 12,940 years ago. In a sheltered bend of a creek, a small band of humans has set up camp. A fire crackles, casting long, dancing shadows against the skin tents. Near the warmth of the hearth, a pair of hands is busy at work—not sharpening a spear point to bring down a mammoth, but delicately crafting something far smaller, far more intimate. With a shard of sharp stone, the artisan scores a tiny, hollow bone from the foot of a hare, snapping it clean. They polish the rough edges against a smooth river stone until they shine. Finally, they rub the small tube with a mixture of animal fat and red iron oxide—ochre—staining it the color of blood, or perhaps the sunrise. This tiny object, no larger than a grain of rice, is threaded onto a piece of sinew and worn.

For nearly thirteen millennia, this scene remained buried beneath the accumulating silts of La Prele Creek. The fire died out, the people moved on, and the memory of that moment was lost to deep time. Until now.

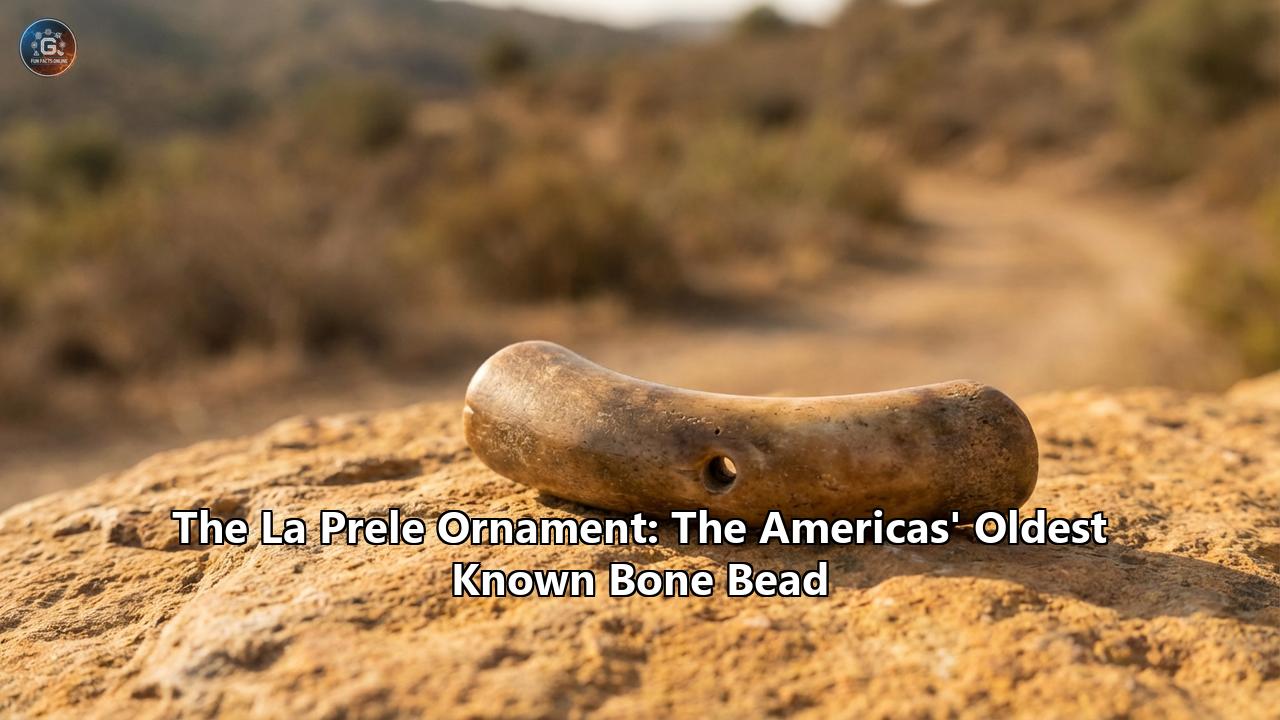

The discovery of the La Prele Ornament, a tube-shaped bone bead measuring a mere seven millimeters in length, has sent ripples through the archaeological community, rewriting our understanding of the First Americans. It is the oldest known bead ever discovered in the Americas, a singular artifact that bridges the vast chasm between the survivalist stereotype of the Ice Age hunter and the complex, creative, and symbolic reality of the Clovis people. This is not just a story about a bead; it is a story about the dawn of art, identity, and culture in the New World.

Part I: The Discovery in the Dust

The story of the La Prele bead begins not with a shout of triumph, but with the quiet, meticulous patience of modern archaeology. The La Prele Mammoth site, located near Douglas, Wyoming, was first identified in 1986. At the time, it was a significant but somewhat enigmatic find: the partial remains of a sub-adult Columbian mammoth associated with a few stone tools. Early excavations led by the legendary George Frison suggested that humans had indeed butchered the beast, but legal disputes with landowners halted work for decades. The site lay dormant, its secrets locked away in the earth.

In 2014, a new chapter began. A team led by Dr. Todd Surovell from the University of Wyoming, along with collaborators including Wyoming State Archaeologist Spencer Pelton, returned to La Prele. They weren't just looking for big bones this time; they were looking for the subtle signature of daily life. They knew that where a mammoth was killed and butchered, a camp would likely be nearby—a place where people ate, slept, repaired their tools, and lived their lives.

The team’s persistence paid off. They uncovered not just a kill site, but a campsite. They found hearths—ancient fire pits still stained with charcoal and ash. They found "activity areas," distinct spots where specific tasks like hide scraping or tool knapping took place. It was in one of these domestic spaces, amidst the scatter of stone flakes and fragmented animal bones, that the bead was found.

It didn't look like much at first—a tiny, reddish cylinder mixed in with thousands of other fragments. It was recovered during the screening process, where buckets of sediment are washed through fine mesh to catch the smallest artifacts that the human eye might miss in the trench. Had the mesh been just a few millimeters larger, the bead would have been lost forever.

When the researchers cleaned and examined the artifact under a microscope, its true nature became undeniable. This was no natural bone fragment. It had been intentionally modified. The ends were rounded and polished, smoothed by the friction of human hands or perhaps by rubbing against clothing for years. The surface bore the distinct, U-shaped incisions of stone tools. And most tellingly, it was coated in red ochre, a pigment that has held deep ritual and symbolic significance for humans across the globe for tens of thousands of years.

Part II: The Science of the Small

Identifying the bead was only the first step. The next challenge was to determine what it was made of. To the naked eye, it was just "bone." But in the high-stakes world of Paleoindian archaeology, specifics matter. Was it a bird bone? A small mammal? A fragment of the mammoth itself?

To answer this, the team turned to a cutting-edge technology known as Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry, or ZooMS. Traditional morphological identification—looking at the shape of the bone—was impossible because the bead had been so heavily worked and polished that its original anatomical features were obscured. ZooMS, however, looks at the molecular fingerprint of the bone collagen.

The results were a surprise. The bead was fashioned from the metapodial (foot bone) or proximal phalanx (toe bone) of a hare.

This revelation was groundbreaking. While archaeologists had long assumed that Clovis people—the group associated with this time period—ate small game, the archaeological record is dominated by the bones of megafauna: mammoths, mastodons, and bison. The massive bones of these beasts survive the ravages of time far better than the delicate skeletons of rabbits and hares. The La Prele bead provided the first secure evidence that Clovis people were utilizing hares, not just for food, but for raw materials.

The choice of material is fascinating. A hare's foot bone is naturally tubular and lightweight, making it an ideal pre-form for a bead. It suggests a resourcefulness and an intimate knowledge of the anatomy of the animals they shared their world with. It also implies that the hunt for the mammoth was punctuated by the trapping of smaller game, a critical survival strategy that is often overshadowed by the drama of the big kill.

Dating the bead was another triumph of modern science. The bone itself was too small and precious to destroy for radiocarbon dating. Instead, the team relied on the impeccable context of the site. The bead was found in a sealed archaeological layer, sandwiched between geological strata that could be securely dated. By dating the charcoal from the associated hearths and the collagen from larger bones in the same cluster, the team determined that the bead—and the camp it belonged to—dated to approximately 12,940 years ago. This places it firmly in the Clovis period, making it the oldest confirmed bead in the Western Hemisphere.

Part III: The Clovis World

To truly appreciate the significance of this tiny artifact, we must step back and look at the world of its creators. The Clovis people are often described as the first "culture" of North America. While recent evidence suggests people may have arrived earlier, Clovis represents the first widespread, recognizable culture, famous for their distinctively fluted stone spear points found from coast to coast.

For decades, the popular image of the Clovis people was one of "big game hunters"—stoic men in furs, clutching spears, facing down angry mammoths. It was a masculine, action-oriented view of prehistory. But the La Prele site, and the bead specifically, shatters this monochrome lens.

The presence of a bead tells us that these people were not merely surviving; they were expressing themselves. In the hierarchy of human needs, personal ornamentation sits well above the baseline of food and shelter. It speaks to a sense of self, a sense of belonging, and a sense of beauty.

Why wear a bead? In anthropological terms, ornaments serve as signals. They can signal age, marital status, tribal affiliation, or individual achievement. In a landscape where population density was incredibly low—where you might go months without seeing another band of humans—visual signals were vital. Meeting a stranger on the vast plains of the Pleistocene, a bead or a pattern of ochre might instantly communicate, "I am one of you," or "I am a friend."

The use of red ochre on the bead adds another layer of meaning. Red ochre (hematite) is found at archaeological sites around the world, dating back hundreds of thousands of years. It is almost famously associated with ritual—burials, cave art, and body painting. At La Prele, archaeologists found a large stain of red ochre near the bead, suggesting a work area where pigment was processed. The source of this ochre was traced to the Powars II quarry, located over 100 kilometers away. This implies that the Clovis people were either traveling vast distances to procure this sacred material or trading with other groups. The bead wasn’t just a pretty object; it was a "foreign" object, imbued with the power of a distant place.

Part IV: The Domestic Sphere

The La Prele site offers a rare glimpse into the "domestic sphere" of the Ice Age—the home life of the Clovis people. The site is not just a scatter of bones; it is a map of a community.

The excavations revealed distinct "hearth-centered activity areas." Imagine a circle of light from a fire. Within that circle, people sat and worked. One area might be rich in tiny stone flakes, marking the spot where a knapper repaired a broken spear point. Another might have a concentration of scrapers and fat residue, where hides were processed.

It was in one of these circles that the bead was found. But it wasn't alone. In a stunning companion discovery, the team also recovered fragments of bone needles.

These weren't the clumsy, thick awls of earlier eras. These were fine, delicate needles with drilled eyes, capable of intricate sewing. Like the bead, they were crafted from the bones of small animals—fox, bobcat, and hare. The implications of this are profound. You don't make fine needles to stitch together heavy, raw mammoth hides. You make them to sew tailored clothing.

The picture of the Clovis people transforms before our eyes. They aren't just draped in rough skins. They are wearing fitted garments, likely with hoods, sleeves, and leggings, necessary to survive the Wyoming winter. These garments are likely decorated—fringed with fur, painted with ochre, and adorned with beads. The La Prele bead was likely not a solitary item but part of a complex ensemble. Was it sewn onto a jacket? Worn as a necklace? Braided into hair?

The presence of needles and beads brings the "invisible" members of the tribe into focus: the women, the elders, the children. While the hunters were out tracking the mammoth, others were back at camp, trapping hares, processing ochre, sewing clothes, and crafting beads. It humanizes the Ice Age. It reminds us that for every hour spent hunting, there were hundreds of hours spent sitting by the fire, talking, teaching, and creating.

Part V: The Mammoth and the Hare

The juxtaposition of the mammoth and the hare at La Prele is poetic. The Columbian mammoth was a titan of the distinct ecosystem known as the "mammoth steppe." Standing up to 13 feet tall at the shoulder, it was a walking mountain of meat, fat, and ivory. Killing one was a monumental task, requiring coordination, bravery, and high-tech weaponry (the Clovis point).

But a society cannot live on mammoth alone. The success of the hunt was never guaranteed. The hare, by contrast, represents the reliability of the small. Hares and rabbits are fast breeders, available year-round, and can be caught with snares—a technology that leaves no trace in the archaeological record but was almost certainly used.

The bead bridges these two worlds. The hunter who wore it might have stood over the carcass of the mammoth, the red bead against their chest echoing the blood of the kill. Or perhaps it was worn by the child who helped check the snares, a first talisman of their contribution to the tribe.

The choice of hare bone might also have had symbolic weight. In many indigenous cultures, animals are not just food; they are kin, possessing spirits and specific characteristics. Was the hare revered for its speed? Its ability to hide? Its fertility? Wearing a piece of the hare might have been a way to invoke those qualities.

Part VI: A Connection to the Old World

One of the most intriguing aspects of the La Prele bead is its similarity to artifacts found halfway across the world. Tubular bone beads, marked with similar incisions and polished in the same way, have been found in Upper Paleolithic sites in Siberia and Eastern Europe, dating back over 20,000 years.

This similarity is not a coincidence. It is a thread of continuity. The ancestors of the Clovis people crossed the Bering Land Bridge (Beringia) from Siberia, bringing with them not just their genes, but their culture. They brought the knowledge of how to flake stone, how to sew tailored clothes, and how to make beads.

For a long time, there was a disconnect in the archaeological record. We knew people in the Old World made beads. We assumed the First Americans did too. But until La Prele, the physical proof was elusive. The La Prele ornament serves as the "missing link" in the chain of artistic tradition. It confirms that the aesthetic sensibilities of the Ice Age carried over into the New World intact. The first people to walk onto the American continent did so wearing jewelry.

Part VII: The Mystery of the Markings

The bead is not a smooth, uniform tube. It bears two distinct, parallel incisions perpendicular to its long axis. What were they for?

Archaeologists have debated this. Are they decorative? Symbolic? Or merely functional?

Some theories suggest they could be "tally marks"—a way of counting kills, days, or moons. Others suggest they were grooves to help secure the bead to a piece of clothing or to keep it in place on a string.

However, a closer look at microscopic wear patterns on similar artifacts suggests they might be purely aesthetic—a way to catch the light, to add texture, or to hold the red ochre pigment more effectively. In the flickering light of a hearth, a smooth bone might look dull, but a grooved, ochre-filled bead would shimmer and stand out.

There is also the possibility of "skeuomorphism"—where an object is made to resemble something else. Could the bone bead have been carved to look like a segment of a plant stalk, or a different kind of animal part? The ambiguity is part of the allure. We can never know the precise intent of the maker, but we can feel their desire to modify the world, to leave a mark, to make a "thing" out of a raw material.

Part VIII: The Younger Dryas and the End of an Era

The timing of the La Prele camp is critical. 12,940 years ago places it squarely in the middle of the Clovis period, but also on the precipice of disaster.

Shortly after this bead was made, the world changed. The climate, which had been warming, slammed back into a deep freeze known as the Younger Dryas. Temperatures plummeted. Ecosystems collapsed. The great megafauna—the mammoth, the mastodon, the American horse—began to slide toward extinction.

The Clovis culture, so perfectly adapted to the world of the mammoth steppe, vanished with it. The fluted points disappeared, replaced by new technologies adapted to a bison-rich world (like Folsom points).

The La Prele bead is, therefore, a relic of a twilight world. It is a snapshot of a culture at its peak, just before the fall. It makes the artifact feel incredibly fragile. The person who wore it lived in a world of giants that was about to vanish forever. Did they sense the changing winds? Did they notice the herds getting smaller, the winters getting longer?

Part IX: The Importance of "Avocational" Archaeology

The story of the La Prele site is also a testament to the relationship between professional archaeologists and the public. The site was originally found by local residents. In Wyoming, "avocational" archaeologists—passionate hobbyists—play a massive role in discovering sites.

The collaboration at La Prele shows how science benefits when the ivory tower opens its doors. The initial discovery, the landowner's permission, and the local knowledge of the terrain were all essential precursors to the high-tech ZooMS analysis. It reminds us that the history of the Americas belongs to everyone, and its recovery is a shared responsibility.

Part X: Speculation: The Life of the Bead

Let us indulge in a moment of narrative speculation, grounded in the facts we have.

Imagine a young woman, perhaps sixteen winters old. She sits by the fire at La Prele. The air smells of roasting hare and sagebrush. She holds the foot of the hare she trapped earlier that morning—a small victory contributing to the band's survival. She uses a flake of chert, sharp as a razor, to score the bone. She snaps it. It is rough.

She spends the evening grinding it against a sandstone block, the rhythmic shhh-shhh sound blending with the low murmur of the elders' voices. She mixes the red dust brought by her uncle from the Sunrise Quarry with a drop of bison fat. She rubs the paste into the bone. It turns a deep, rich red.

She takes a bone needle—one she made herself from the leg of a bobcat—and threads a piece of sinew. She sews the bead onto the fringe of her hood. When she walks, it clicks softly against another bead.

The next day, the hunters return. They have killed a mammoth—a young one, stranded in the creek mud. The camp erupts in activity. For days, they butcher, feast, and work. The bead witnesses it all.

Eventually, the mammoth is stripped. The smell of decay begins to attract wolves. It is time to move. In the chaos of packing—striking tents, gathering tools—the bead catches on a branch or a piece of gear. The sinew snaps. The bead falls silently into the dust near the hearth.

The woman searches for it, but the ash is deep, and the time is short. She leaves it behind. She walks away, following the creek, leaving her mark in the earth.

Thirteen thousand years later, a trowel scrapes the dirt, and the sun touches the bead once again.

Part XI: Why It Matters Today

Why should we care about a tiny bone tube in an age of digital revolution and space travel?

Because it anchors us. The La Prele ornament reminds us that creativity is not a modern luxury; it is a fundamental human trait. We are a species that decorates. We are a species that finds meaning in materials. We are a species that connects with our environment—the hare, the mammoth, the stone, the ochre—to build our identity.

The bead also challenges the "brutish" view of the past. Life in the Ice Age was hard, yes. It was dangerous. But it was not devoid of beauty. The people who lived then were behaviorally modern humans. They had the same brains, the same emotions, and the same capacity for art as we do. They loved their children, they mourned their dead, and they adorned their bodies.

The La Prele Mammoth site continues to be excavated. Who knows what else lies in the Wyoming dirt? A flute? A carving? Another bead? Every summer, Surovell and his team peel back another layer of the onion, bringing us face-to-face with our ancestors.

But for now, the La Prele Ornament stands alone—or rather, it stands first. The oldest bead in the Americas. A tiny, red, hollow bone that echoes with the voices of the deep past, telling us: "We were here. We were creative. We were human."

The wind still blows across the Wyoming plains, but now, when we listen, we can hear the faint click of bone beads, a whisper of a culture that laid the foundation for the human story in the New World. The La Prele bead is not just an artifact; it is a time machine, and it has only just begun to tell its story.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Prele_Mammoth_Site

- https://cowboystatedaily.com/2024/02/25/why-discovery-of-a-small-13-000-year-old-bead-in-wyoming-is-a-big-deal/

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/La-Prele-bone-bead-showing-polished-ends-upper-and-side-view-with-incisionslower_fig2_377975657

- https://www.cuyamungueinstitute.com/articles-and-news/ancient-bone-oldest-known-bead-in-the-americas/

- https://wyoarchaeo.wyo.gov/index.php/learn/wyoming-archaeology-awareness-month/project-a-day/72-september-17-the-la-prele-mammoth-site

- https://www.academia.edu/96051418/The_La_Prele_Mammoth_Site_Converse_County_Wyoming_USA

- https://www.heritagedaily.com/2024/02/archaeologists-find-the-oldest-known-bead-in-the-americas/150545

- https://www.uwyo.edu/news/2024/02/uw-archaeology-professor-discovers-oldest-known-bead-in-the-americas.html

- https://archaeology.org/news/2024/12/05/ice-age-bone-needles-discovered-in-wyoming/

- https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/13000-year-old-bone-bead-is-the-oldest-of-its-kind-in-the-americas

- https://www.sci.news/archaeology/clovis-bead-12683.html

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/the-clovis-culture-people-lifestyle-artifacts.html

- https://www.crystalinks.com/clovis.html

- https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/anthropology/clovis-culture

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20555563.2025.2568819

- https://www.iflscience.com/13000-year-old-animal-bone-needles-unearthed-at-mammoth-hunting-base-in-wyoming-77008

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gyVXh25hmh4

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clovis_culture

- https://www.uwyo.edu/news/2024/11/uw-based-research-shows-early-north-americans-made-needles-from-fur-bearers.html