The Liquid Tightrope: How Nature's Water-Walkers Are Inspiring a New Breed of Amphibious Robots

Nature, the grand architect of life, has long been the ultimate muse for engineers and scientists. In the relentless crucible of evolution, organisms have developed solutions to locomotion challenges that are elegant, efficient, and often, utterly astonishing. From the effortless flight of a bird to the powerful gallop of a cheetah, the biological world is a library of engineering marvels. But perhaps one of the most captivating and seemingly physics-defying feats is the ability to walk on water. This is not the realm of miracles, but of intricate biomechanics and fluid dynamics, mastered by creatures both minuscule and surprisingly large.

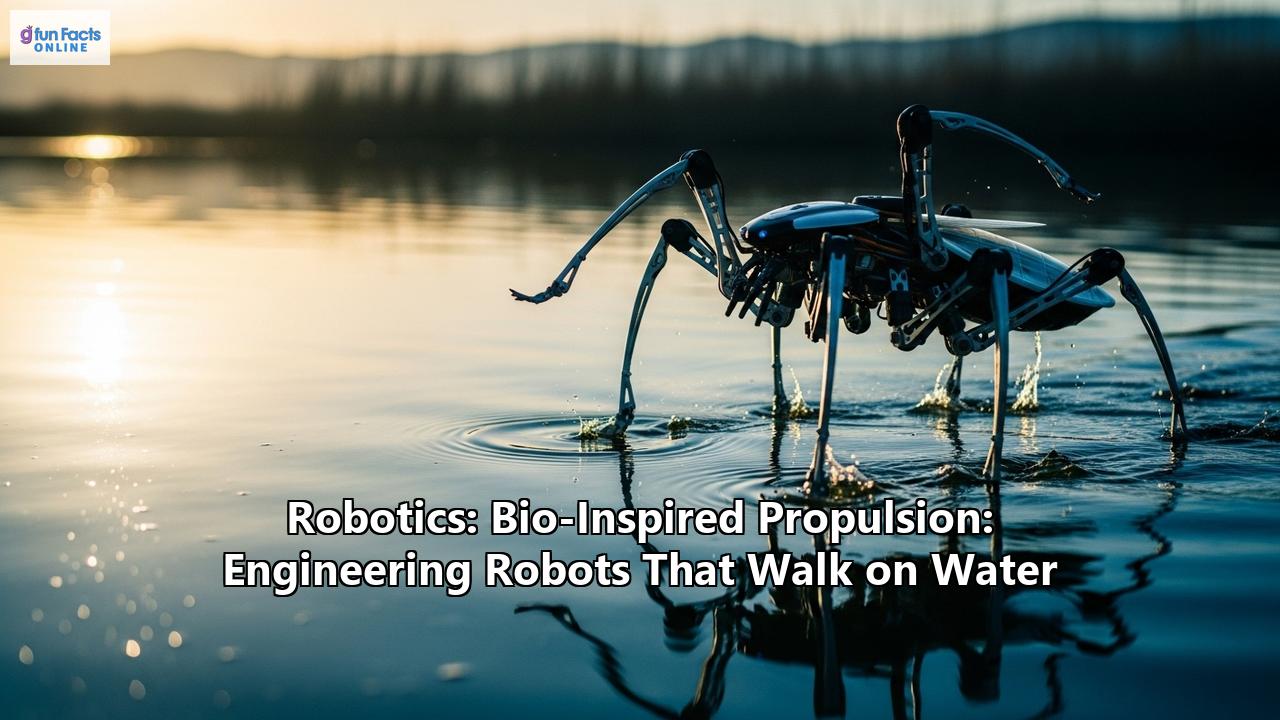

For centuries, we have observed the delicate dance of the water strider on the surface of a still pond and the explosive sprint of the basilisk lizard across a jungle stream. These animals have unlocked the secrets of the liquid tightrope, treating the water's surface not as a barrier to be breached, but as a substrate to be exploited. Now, in labs across the world, roboticists are diligently studying these natural masters, translating their biological principles into a new generation of machines: robots that can walk, run, and leap from the water's surface.

This burgeoning field of bio-inspired propulsion is more than just a scientific curiosity; it represents a paradigm shift in how we design robots for complex, transitional environments. The ability to traverse both land and water with equal agility could revolutionize everything from environmental monitoring and search and rescue missions to covert surveillance and space exploration. This article delves into the fascinating world of water-walking robots, exploring the biological blueprints that inspire them, the engineering challenges of replicating nature's genius, and the future possibilities that await once we truly master the art of walking on water.

Part 1: Nature's Grand Designs: The Masters of Surface Locomotion

To build a robot that can walk on water, we must first become students of the creatures that have been doing it for millennia. Two animals, in particular, stand out as the archetypes of aquatic surface locomotion, each employing a distinct physical principle to achieve this remarkable feat: the water strider and the basilisk lizard.

The Water Strider: Harnessing the Power of Surface Tension

The water strider (family Gerridae) is the epitome of grace and efficiency on the water's surface. These small insects, typically about a centimeter long, can be seen gliding effortlessly across ponds and slow-moving streams. Their secret lies in their mastery of a fundamental property of water: surface tension. Water molecules are highly attracted to one another, and at the surface, where there is only air above, this attraction creates a cohesive film, a sort of elastic membrane. For an insect as light as a water strider, this membrane is strong enough to support its weight.

But it's not just their low weight that allows them to stay afloat; their legs are a marvel of natural engineering. The legs of a water strider are long and slender, which allows them to distribute their body weight over a large area, preventing any single point from exerting enough pressure to break the surface tension. More importantly, their legs are covered in a dense carpet of tiny, water-repellent hairs called microsetae. These hairs, which can number in the thousands per leg, are themselves adorned with even finer nanogrooves, creating a hierarchical structure.

This intricate, multi-level structure is key to the water strider's superhydrophobicity—its extreme water-repelling property. The micro and nanostructures trap a layer of air between the leg and the water, which dramatically reduces the contact area and prevents the leg from getting wet. This air cushion allows the leg to rest in a dimple on the water's surface, supported by the upward force of surface tension. The water contact angle on their legs can be as high as 161.5 degrees, far exceeding the 90-degree threshold for hydrophobicity. A waxy coating on the legs further enhances this water-repelling effect. The total supporting force generated by a single leg can be up to 15 times the entire body weight of the insect, providing a huge margin of safety.

For propulsion, it was once thought that water striders pushed off against the tiny capillary waves they created. However, research has revealed a more complex and efficient mechanism. High-speed video analysis has shown that as the strider performs its sculling motion with its middle pair of legs, it creates hemispherical vortices in the water beneath the surface. It is the momentum transferred to these vortices that propels the insect forward, a much more effective method than relying on weak surface waves. This discovery resolved what was known as "Denny's paradox," which questioned how infant water striders, too slow to generate waves, could move.

Some species of water striders, like the ripple bug Rhagovelia, have taken this a step further. They possess unique, fan-like structures on their feet that passively deploy upon contact with water, creating a larger, more effective oar. This allows them to navigate even fast-flowing, turbulent streams with incredible agility.

The Basilisk Lizard: The Power of Brute Force and Hydrodynamics

If the water strider is a delicate ballet dancer on the water's surface, the basilisk lizard (Basiliscus genus) is a powerful sprinter. Known colloquially as the "Jesus Christ lizard," this reptile, which can weigh up to 100 grams, is far too heavy to be supported by surface tension alone. Instead, it employs a dynamic and forceful strategy to literally run across the water for distances of up to 4.5 meters (about 15 feet) to escape predators.

The basilisk's water run is a complex, three-phase process executed with incredible speed and precision. It all starts with the slap. The lizard slams its foot down onto the water surface with great force and speed. This action pushes water out of the way and generates an initial upward force.

This is immediately followed by the stroke. As the foot plunges downward, it creates a large air cavity around it. The lizard then pushes its foot backward against the water at the back of this cavity, generating both lift to keep it from sinking and thrust to propel it forward. The greatest propulsive forces are generated during this phase, when the foot is moving primarily downwards and backwards.

The final and most critical phase is the recovery. Before the air cavity collapses and water rushes back in, the lizard must quickly retract its foot. Pulling the foot out of the air cavity is much easier than pulling it through the water, which would create significant drag and pull the lizard down. This entire slap-stroke-recovery cycle is performed at an astonishing rate, with the lizard taking many steps per second.

The basilisk's feet are also specially adapted for this task. They have long toes with fringes of skin that unfurl when they hit the water, increasing the surface area and the amount of force they can exert. The lizard's tail also plays a crucial role, acting as a counterbalance to maintain stability as it careens across the surface. Interestingly, studies using digital particle image velocimetry have shown that the lizard generates significant side-to-side forces, suggesting a dynamic, if somewhat wobbly, method of stabilization.

The physics of the basilisk's run is a delicate balance of force, speed, and timing. It's a high-energy, high-impact form of locomotion that stands in stark contrast to the water strider's serene gliding. A 175-pound human attempting to replicate this feat would need to run at an incredible 65 miles per hour.

Part 2: Engineering Emulation: Building Robots That Walk on Water

The elegance of the water strider and the raw power of the basilisk lizard present two distinct and compelling blueprints for roboticists. Translating these biological principles into mechanical systems is a formidable challenge, pushing the boundaries of material science, actuator technology, and control theory. The result is a fascinating menagerie of water-walking robots, from delicate micro-machines that glide on surface tension to more robust prototypes that seek to replicate the basilisk's dynamic stride.

Replicating the Water Strider: The Rise of the Microrobot

The water strider's reliance on surface tension makes it an ideal model for small-scale robotics. Many early and contemporary designs focus on mimicking its key features: light weight, long, supportive legs, and superhydrophobic surfaces.

One notable example is a bionic aquatic microrobot developed by researchers that closely mimics the real insect. This robot features ten superhydrophobic supporting legs and two oar-like actuating legs powered by miniature DC motors. The superhydrophobic property of the legs was crucial, and theoretical models confirmed that the leg's radius and a high water contact angle were the most significant factors in generating the large supporting force needed to stand and move on the water's surface. Such robots, often low-cost and easily fabricated, are seen as having great potential for applications like water quality monitoring.

The challenge with DC motor-based designs is often their weight and the need for numerous supporting legs to distribute that weight, which can increase drag and limit speed and maneuverability. To overcome this, researchers have turned to advanced smart materials for actuation, which offer advantages like being lightweight and having high power densities.

One promising approach involves the use of shape memory alloys (SMA). SMAs are materials that "remember" their original shape and return to it when heated. By running a current through an SMA wire, it can be made to contract, producing a motion that can power a robot's leg. Researchers have developed a water-walking robot weighing only 0.236 grams that uses a "compliant amplified shape memory alloy actuator" (CASA). This design amplifies the small strain of the SMA wire to create a wide, 80-degree sculling motion with the actuating legs, much like a real water strider. This robot achieved impressive speeds and the ability to turn, demonstrating the potential of SMA-based actuation. However, a major challenge with SMAs is their thermal nature; they can be inefficient in water due to high heat transfer rates, a problem researchers are trying to solve by encapsulating the SMA wires in soft, insulating structures.

Another alternative is the use of piezoelectric actuators. These materials change shape when an electric voltage is applied, allowing for very fast and precise movements. Researchers have developed amphibious microrobots driven by piezoelectric actuators that can both walk on land and swim through water. One such robot, with a body length of 4.5 cm and a mass of 1.4 g, uses two active front legs for walking and two caudal fins for swimming, with the actuators integrated directly into the leg and fin structures. It achieved a land speed of 15.3 cm/s and an underwater speed of 9.1 cm/s, showcasing the versatility of this technology.

The Harvard Ambulatory MicroRobot (HAMR) is a prime example of a highly advanced, multi-modal microrobot. Originally designed for terrestrial locomotion, an amphibious version was developed with specially designed foot pads that use surface tension to keep it afloat. It can "swim" across the surface by moving its legs at up to 10 Hz. In a remarkable innovation, HAMR can also intentionally sink itself. By applying a voltage to its footpads, it uses a process called electrowetting to reduce the water's contact angle, breaking the surface tension and allowing it to submerge and walk on the bottom. Getting back out of the water proved to be a significant challenge, requiring a stiffened transmission and special pads on its front legs to provide enough friction to climb an incline. The power and control for such untethered microrobots are also significant engineering feats, with custom circuit boards and tiny batteries needed to drive the piezoelectric actuators.

More recently, inspiration has been drawn from the Rhagovelia ripple bug. Engineers at Ajou University, in collaboration with UC Berkeley and Georgia Tech, created "Rhagobot," an insect-sized robot with fan-like oar tips on its legs. These fans passively open when they enter the water and collapse when withdrawn, mimicking the natural mechanism to maximize thrust and minimize drag without requiring any extra energy or muscle-like actuation. This design significantly improved the robot's thrust, braking, and turning capabilities, opening the door for highly agile robots that can operate in turbulent water.

Chasing the Basilisk: The Quest for Dynamic Water Running

Replicating the dynamic, high-force locomotion of the basilisk lizard presents a different and arguably more difficult set of challenges. This approach is less common in robotics, primarily due to the immense power-to-weight ratio required to generate the necessary forces.

Early research in this area, such as the work on the "Water Runner Robot" at Carnegie Mellon University, focused on understanding and optimizing the basilisk's motion. Researchers used computer simulations to analyze the slap, stroke, and recovery phases, exploring how to generate enough lift and thrust to support a robot much heavier than the lizard itself. These simulations showed potential efficiency gains over the biological model, particularly with designs using multiple sets of running legs.

The primary challenge lies in scalability. While a small, lightweight robot might get away with using surface tension, a larger, basilisk-inspired robot must generate significant hydrodynamic lift. This requires powerful, fast-acting actuators and a lightweight yet robust structure, a combination that is difficult to achieve. The forces involved also create significant stability problems; as the basilisk demonstrates, this type of locomotion involves large, destabilizing side-to-side forces that must be actively controlled.

While a fully functional, autonomous basilisk-like running robot remains a long-term goal, the research into its hydrodynamics provides valuable insights for any robot that needs to interact with the water surface in a dynamic way. The principles of creating and utilizing air cavities to reduce drag during limb retraction, for instance, could be applied to other amphibious robot designs.

Part 3: The Broader Context and Overarching Challenges

The quest to build water-walking robots does not exist in a vacuum. It is part of the broader field of bio-inspired aquatic robotics, which looks to a diverse array of marine life to design more efficient, maneuverable, and stealthy underwater vehicles. Understanding this larger context helps to appreciate the unique niche and challenges of surface locomotion.

A Sea of Inspiration: Beyond Walking

Nature's solutions to aquatic propulsion are incredibly varied. Many research efforts focus on emulating the undulatory swimming of eels and fish. Robots inspired by these creatures, like the Black Ghost Knifefish, use flexible fins to create traveling waves along their bodies, resulting in highly efficient and stable movement. This method is particularly well-suited for maneuverability in confined spaces and has applications in underwater exploration and environmental monitoring.

Another common source of inspiration is jet propulsion, as seen in squid and jellyfish. These animals expel water to generate thrust, a method that can allow for rapid bursts of speed. Roboticists have developed systems that mimic this, offering high maneuverability, though sometimes at the cost of lower efficiency compared to undulatory methods.

Compared to these fully submerged methods, water-walking presents a unique set of advantages and disadvantages. It allows for direct access to the air for communication (e.g., GPS, WiFi) and solar power, something that is a major challenge for underwater vehicles which must rely on acoustics or tethers. It also enables a seamless transition to land-based locomotion. However, it is also inherently less stable, being subject to waves and surface disturbances, and for larger robots, requires a massive expenditure of energy.

The Grand Challenges of Water-Walking Robotics

Whether mimicking the delicate strider or the powerful basilisk, engineers face a common set of formidable challenges that must be overcome to create practical, real-world water-walking robots.

1. Scalability and the Tyranny of the Square-Cube Law: The physics of water-walking changes dramatically with size. For a water strider, surface tension forces, which scale with length, dominate over gravitational forces, which scale with volume (or length cubed). As an object gets larger, its weight increases much faster than the surface area available to support it. This is why a human-sized water-walking robot based on surface tension is impossible. A basilisk-style robot faces a similar scaling problem: its power requirements to generate sufficient hydrodynamic lift would increase astronomically with size, making it incredibly difficult to build a power source and actuators that are both strong enough and light enough. This is perhaps the single greatest barrier to creating large-scale water-walking robots. 2. Power and Control: Microrobots face a constant battle to carry their own power. Batteries add significant weight, a critical factor for any robot trying to stay on the water's surface. The actuators themselves, whether SMA, piezoelectric, or motor-based, have different power demands and control complexities. Untethered operation requires sophisticated, custom-built circuit boards that can generate the necessary voltages and control signals within a tiny footprint. Furthermore, controlling a robot on a dynamic, yielding surface like water requires advanced feedback systems and algorithms to maintain stability and execute precise maneuvers. 3. The Land-Water Transition: For many proposed applications, the ability to move from land to water and back again is crucial. This transition is fraught with difficulty. As the HAMR robot demonstrated, the same surface tension that holds a robot up can become a powerful barrier preventing it from exiting the water. Overcoming this adhesive force requires specialized mechanisms, such as increasing friction or even developing jumping capabilities. Robots with legs designed for water-walking may not be optimized for efficient movement on solid ground, requiring complex, multi-modal limb designs. 4. Robustness and Environmental Adaptation: The real world is not a sterile laboratory tank. A practical water-walking robot must be able to cope with wind, waves, currents, and surface debris. For a strider-like robot, even a small wave could be catastrophic, while a basilisk-like robot would need to constantly adjust its power output and balance to deal with a non-uniform surface. Building robots that are robust enough to handle these unpredictable conditions is a major engineering hurdle.Part 4: The Future is Amphibious: Applications and Horizons

Despite the challenges, the potential rewards of mastering water-walking robotics are immense. The unique capabilities of these amphibious machines could open up entirely new possibilities in a wide range of fields.

Environmental Monitoring and Scientific Research: Imagine swarms of low-cost, water-strider-like robots skimming across a lake, collecting water quality data in real-time. Their ability to traverse the surface and potentially crawl onto land to deploy sensors or take samples would provide an unprecedented level of detail for ecologists studying aquatic ecosystems. They could be used to monitor for pollution, track algal blooms, or study the behavior of other aquatic life with minimal disturbance to the natural environment. Search and Rescue: In disaster scenarios like floods, amphibious robots could be invaluable. They could be deployed to navigate flooded urban areas, searching for survivors in places inaccessible to boats or human rescuers. Their ability to transition from water to rubble-strewn land would make them uniquely suited for these complex and dangerous environments. Infrastructure Inspection: Small robots could walk along the water inside pipes, inspecting for leaks or blockages without requiring the system to be drained. This could revolutionize the maintenance of our aging water infrastructure, saving time, money, and precious water resources. Surveillance and Security: The stealthy nature of small, water-walking robots makes them ideal for surveillance applications. They could patrol harbors, reservoirs, or other sensitive areas, providing a persistent monitoring presence from a unique vantage point.Looking further ahead, the principles being developed for water-walking robots could even find applications in space exploration. A robot capable of traversing the liquid methane lakes of Titan, for example, would be a game-changer for planetary science.

The journey to create a true water-walking robot is a testament to the power of bio-inspiration. It is a field where biology, physics, and engineering converge, where the intricate dance of a tiny insect and the explosive power of a sprinting lizard provide the roadmap for the technologies of tomorrow. While significant challenges remain, the progress has been remarkable. From the first tentative robotic steps on a laboratory water bath to the agile, multi-modal microrobots of today, we are steadily closing the gap between the natural world and our own creations. The liquid tightrope, once the exclusive domain of nature's specialists, is now within the grasp of our robotic emissaries, and as they begin to walk, run, and explore this challenging interface, they will undoubtedly open up a world of possibilities we are only just beginning to imagine.

Reference:

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10624607_The_hydrodynamics_of_water_strider_locomotion

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21650460/

- https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/surface-tension-allows-a-water-strider-walk-water

- https://www.scientific.net/AMM.459.551

- https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0405736101

- https://www.scientific.net/AMM.459.547

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17385899/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7231474/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/43342181_Experimental_determination_of_the_efficiency_of_nanostructuring_on_non-wetting_legs_of_the_water_strider

- https://hoogle.gatech.edu/Publications/Hu03.pdf

- https://www.bohrium.com/paper-details/the-hydrodynamics-of-water-strider-locomotion/812394167786274816-8233

- https://coe.gatech.edu/news/2025/08/tiny-fans-feet-water-bugs-could-lead-energy-efficient-mini-robots

- https://news.berkeley.edu/2025/08/21/wing-like-fans-on-the-feet-of-ripple-bugs-inspire-a-novel-propulsion-system-for-miniature-robots/

- https://physicsworld.com/a/could-athletes-mimic-basilisk-lizards-and-turn-water-running-into-an-olympic-sport/

- https://enviroliteracy.org/animals/how-does-a-lizard-run-on-water-and-not-sink/

- https://enviroliteracy.org/animals/what-is-the-ability-of-a-basilisk-jesus-lizard-to-run-across-water/

- https://wonderopolis.org/index.php/wonder/how-does-the-basilisk-lizard-run-on-water

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/am200382g

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51199622_Bioinspired_Aquatic_Microrobot_Capable_of_Walking_on_Water_Surface_Like_a_Water_Strider

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10807579/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9027874/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360043068_Design_of_a_Biologically_Inspired_Water-Walking_Robot_Powered_by_Artificial_Muscle

- https://wsuamsl.com/resources/ICRA@40_abstract.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384860925_A_piezoelectric_driven_amphibious_microrobot_capable_of_fast_and_controllable_movement

- https://newatlas.com/hamr-water-walking-robot/55296/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T7GQzWigvTM

- https://www.stem-journal.com/blog/development-of-bio-inspired-soft-robots-for-deep-sea-exploration

- https://library.fiveable.me/underwater-robotics/unit-4/bio-inspired-propulsion-systems/study-guide/FNaEXEwhL02FpDxT

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHEtV__ko2I

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281932845_Development_of_a_Bio-Inspired_Underwater_Robot_Prototype_with_Undulatory_Fin_Propulsion

- https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/6/2556

- https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/figshare-production-eu-deakin-storage4133-ap-southeast-2/coversheet/37086331/1/joordensunderwaterswarm2016.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA3OGA3B5WOX2T3W6Z/20250817/ap-southeast-2/s3/aws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20250817T140213Z&X-Amz-Expires=86400&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Signature=d929cfef5a35bc0536628379817bca5c1cc63fdf632d562d8c24061057a9089d

- https://www.artiba.org/blog/5-challenges-to-address-in-scaling-robotics-solutions-in-the-workforce

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386501388_Advances_in_Bio-inspired_Swimming_Robots_for_Underwater_Exploration_A_Review

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8540518/

- https://www.mdpi.com/2072-666X/6/9/1346

- https://www.mdpi.com/2313-7673/10/6/396

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382878822_Bio-Inspired_Robotics_for_Underwater_Exploration

- https://www.autodesk.com/design-make/articles/acwa-robotics

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYoOCwjoD7U