The Universe, for all its violent chaos, was once thought to be a place of geometric perfection. For decades, astronomers and physicists modeled the death of massive stars—supernovae—as perfect spheres. In this idealized version of the cosmos, a star would collapse in on itself and then explode outward in a uniform, expanding ball of fire, like a balloon inflating in all directions at once. It was a neat, symmetrical mathematical solution.

It was also wrong.

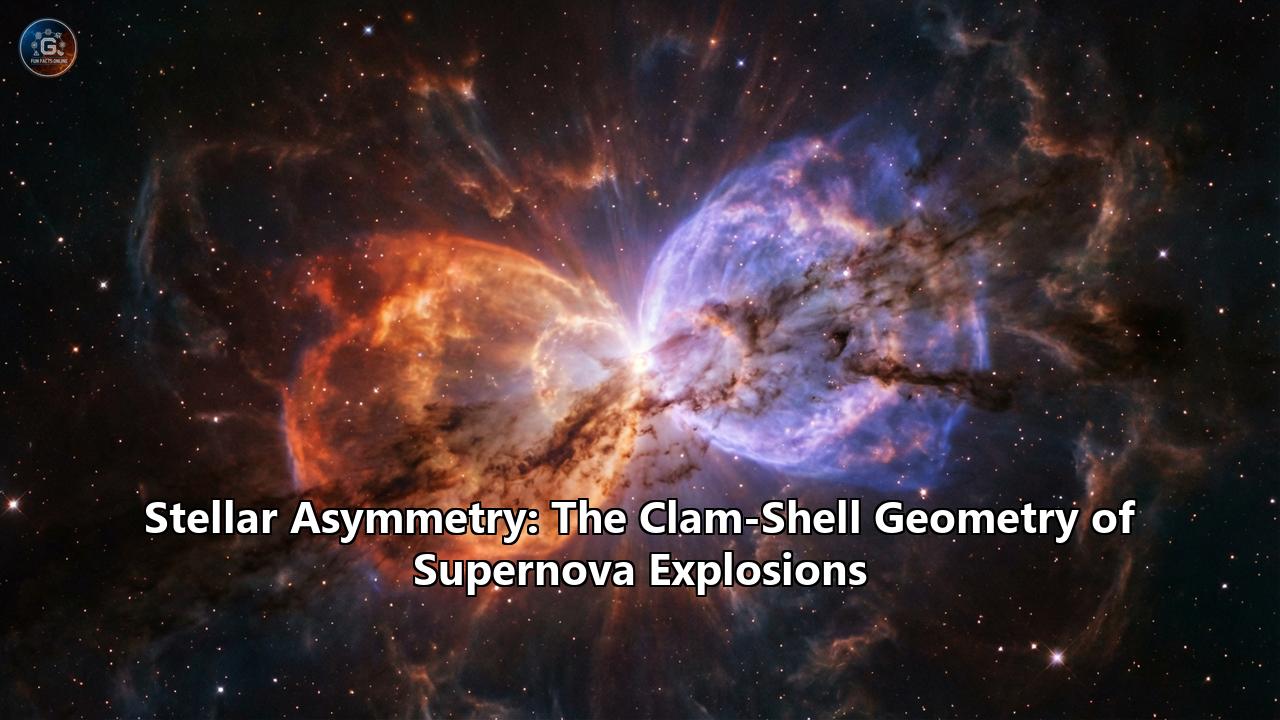

Recent breakthroughs in 3D computer modeling, combined with high-fidelity observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Chandra X-ray Observatory, have shattered the spherical illusion. We now know that supernova explosions are messy, chaotic, and profoundly asymmetric. They do not expand as spheres; they expand as lopsided, turbulent, and complex structures that astronomers are increasingly describing with a new geometric vocabulary. Among the most compelling of these shapes is the "Clam-Shell" geometry—a morphology defined by bipolar lobes, broken rims, and a "sloshing" internal engine that breaks the star apart not with a pop, but with a directional, uneven kick.

This article explores the fascinating world of stellar asymmetry, tracing the journey from the spherical cow models of the 20th century to the high-resolution, clam-shell realities of today. We will dive deep into the quantum mechanics that drive these explosions, the fluid dynamics that shape them, and the specific supernova remnants—like Cassiopeia A and SN 1987A—that serve as the smoking guns for this chaotic new physics.

Part I: The Spherical Illusion

To understand why the "clam-shell" geometry is revolutionary, we must first understand the model it replaced. For much of the 20th century, the standard model of a Core-Collapse Supernova (Type II) was spherically symmetric.

The 1D Universe

In the early days of computational astrophysics, computers lacked the processing power to simulate three dimensions. To make the math solvable, physicists assumed spherical symmetry. This effectively turned the star into a 1D problem: you only needed to calculate what was happening along a single line from the center to the surface, and then you could assume it was the same in every other direction.

In this 1D world, the mechanism was simple:

- Collapse: The iron core of a massive star (more than 8-10 times the mass of the Sun) runs out of fuel. Gravity wins, and the core collapses at 25% the speed of light.

- Bounce: The core hits nuclear density and becomes a proto-neutron star. The infalling matter slams into this hard surface and bounces off, creating a shockwave.

- Explosion: This shockwave travels outward, blowing the rest of the star apart in a perfect sphere.

The Failure of the Sphere

There was just one problem: when theorists ran these 1D simulations in the 1980s and 90s, the stars refused to explode. The shockwave, battling against the immense gravity of the infalling matter, would stall within milliseconds. It would run out of energy and die, collapsing back into a black hole. The spherical model predicted that supernovae shouldn't exist. Yet, we see them popping off all over the universe.

Something was missing. The "spark" that revived the stalled shockwave was not just energy—it was entropy and asymmetry. The universe needed to break the sphere to make the star explode.

Part II: The Anatomy of the Clam-Shell

The term "Clam-Shell Geometry" in the context of supernovae is a vivid metaphor for bipolar or unipolar asymmetry. Instead of an expanding beach ball, imagine a clam shell prying open.

- The Hinge: The central neutron star or black hole.

- The Shells: Two massive lobes of ejecta blasting out in opposite directions (bipolar) or a single dominant lobe taking the majority of the matter (unipolar), leaving the other side "empty" or filled with lighter material.

This geometry is characterized by three main structural features that defy the spherical model:

1. The Toroidal Atmosphere

In a rotating star, the infalling matter doesn't just fall straight down; it swirls. This creates a torus (doughnut shape) of dense material around the equator of the dying star. When the explosion happens, the blast wave finds it hard to push through this thick equatorial doughnut. Instead, it takes the path of least resistance: the poles.

This funnels the energy upward and downward, creating two expanding lobes—the top and bottom of the "clam shell."

2. The Broken Rim

In remnants like Cassiopeia A (Cas A), we observe that the "shell" of the supernova is not continuous. It is fragmented. There are large gaps where the explosion was weak and bright knots where it was powerful. This looks remarkably like the jagged edge of a broken shell. These gaps are not random; they are the "fingerprints" of the turbulent bubbles of hot gas that boiled up from the core, breaking through the star's surface in specific patches rather than a uniform sheet.

3. The Displaced Heart

Perhaps the most telling sign of the clam-shell geometry is the "kick." If a supernova were a perfect sphere, the neutron star left behind would sit dead center, motionless. But we observe neutron stars racing through the galaxy at speeds of over 1,000 kilometers per second (over 2 million mph).

This is the Newton's Third Law of supernovae: for the neutron star to be kicked that hard in one direction, the explosion must have been significantly stronger in the opposite direction. The explosion was a "gunshot," shooting the ejecta one way (the open shell) and the neutron star the other (the recoil).

Part III: The Engine of Asymmetry

What creates this clam-shell shape? How does a round star die in a lopsided explosion? The answer lies in the hellish few seconds after the core collapse, driven by three distinct mechanisms.

1. Neutrino-Driven Convection (The Boiling Pot)

When the core collapses, it releases a flood of neutrinos—ghostly particles that carry away 99% of the supernova's energy. These neutrinos heat the material just behind the stalled shockwave.

Imagine a pot of thick oatmeal boiling on a stove. The heat (neutrinos) comes from the bottom (the core). The oatmeal (stellar gas) begins to bubble and convect. These bubbles are not small; they are mushroom clouds thousands of kilometers wide.

As these massive bubbles of hot gas rise, they push the shockwave outward in specific spots. If a giant bubble pushes out on the "north" pole, the explosion bulges that way. This convection breaks the spherical symmetry, creating the lumpy, irregular shape of the initial blast.

2. SASI: The Sloshing Star

The Standing Accretion Shock Instability (SASI) is the leading theory for the clam-shell shape.

Imagine the shockwave as a spherical dam holding back a river of infalling gas. As the gas hits the shock, it doesn't just sit there; it starts to slosh back and forth, like water in a bathtub being carried by a shaky pair of hands.

This sloshing grows more violent over time. The shockwave creates a spiral mode, physically deforming the explosion into a figure-eight or hourglass shape.

- The Slosh: The shock bulges out on one side, then the other.

- The Break: Eventually, the explosion finds a weak point and bursts through, creating a dominant axis. This "sloshing" naturally creates a bipolar (two-lobed) or unipolar (one-lobed) structure, effectively sculpting the "clam-shell" out of the chaos.

3. The Jittering Jets

In stars that are rotating rapidly, the collapse creates an accretion disk around the new neutron star. This disk fires jets of material outward at near light-speed.

However, because the infalling matter is turbulent, the disk isn't stable. It wobbles. The jets don't point in a straight line; they "jitter" around, spraying energy in a cone.

- The Drill: These jets act like a power drill, piercing through the star's outer layers.

- The Cavity: They carve out large cavities—the empty interior of the clam shell—and push the matter into the dense walls of the shell.

Part IV: Case Studies in Asymmetry

The theory of clam-shell geometry is supported by some of the most famous objects in the night sky.

Cassiopeia A: The Broken Shell

Cassiopeia A (Cas A) is the "poster child" for supernova asymmetry. Located 11,000 light-years away, it exploded around the year 1680.

- The Observation: Recent JWST and Chandra images reveal that Cas A is not a sphere. It consists of a "Main Shell" that is heavily fragmented.

- The Jets: Astronomers have identified two distinct "jets" of high-velocity material shooting out of the remnant—one to the Northeast and one to the Southwest. These jets are traveling at 15,000 km/s, much faster than the rest of the shell. This is the classic bipolar structure.

- The Green Monster: In 2023/2024, JWST revealed a structure nicknamed the "Green Monster"—a loop of gas in the interior of the shell. This structure is likely the result of the "sloshing" mechanism (SASI) pushing a wall of debris into the circumstellar material, preserving the memory of the star's final, lopsided death throes.

SN 1987A: The Keyhole

Supernova 1987A, the closest supernova observed in modern times, is explicitly non-spherical.

- The Rings: It is surrounded by three rings—an inner ring and two outer rings—forming an hourglass shape. This is the projection of a bipolar "clam-shell" or dumbbell geometry.

- The Mystery Neutron Star: For 37 years, the neutron star at the center was missing. In 2024, JWST finally found evidence of it. The reason it was hard to find? It was likely kicked or obscured by a dense, asymmetrical dust blob—further proof of a lopsided explosion.

SN 2024ggi: The Olive

In 2024 and 2025, astronomers studied SN 2024ggi, a nearby supernova in the galaxy NGC 3621.

- Polarimetry: Using a technique called spectropolarimetry (measuring the direction of light waves), they mapped the shape of the explosion just hours after it happened.

- The Result: It wasn't round. It was "olive-shaped" or ellipsoidal. This confirmed that the asymmetry is not just something that happens centuries later as the debris hits other gas; it is intrinsic to the explosion itself. The "clam-shell" shape is born in the first second.

Part V: Why It Matters

The shift from "Sphere" to "Clam-Shell" is not just about drawing better pictures. It fundamentally changes our understanding of the universe.

1. The Origin of Elements

We are made of star stuff—calcium in our bones, iron in our blood. These elements are forged in the supernova.

In a spherical explosion, elements would be layered like an onion: Iron in the middle, Oxygen further out, Hydrogen on the outside.

In a clam-shell explosion, the layers are mixed. The turbulent "fingers" of the explosion dredge up iron from the core and shoot it out past the oxygen. This mixing is crucial. If supernovae didn't mix, the heavy elements might fall back into the black hole. The violent asymmetry is what sprays the heavy elements into the galaxy, allowing planets and life to form.

2. Gravitational Waves

A perfect sphere does not emit gravitational waves (ripples in spacetime). A lopsided, sloshing, clam-shell explosion does.

As the core "sloshes" via the SASI mechanism, it shakes the fabric of spacetime. Next-generation gravitational wave detectors (like the Einstein Telescope) are being designed to listen for this specific "hum." Detecting the gravitational wave signal of a clam-shell oscillation would be the ultimate proof of what happens inside the hidden heart of a dying star.

3. The Kick of the Neutron Star

The high-velocity "pulsar kicks" (neutron stars moving at millions of miles per hour) can only be explained by this geometry. If the explosion is a clam-shell that opens to the "north," the neutron star is kicked to the "south." This migration of neutron stars spreads them across the galaxy, seeding different regions with pulsars and magnetars.

Conclusion: The Beautifully Broken Universe

The "Clam-Shell Geometry" of supernova explosions teaches us a profound lesson: perfection is not the default state of nature. The death of a star is a struggle—a violent, turbulent battle between gravity and entropy. The "clam-shell" shape—with its broken rims, bipolar jets, and off-center heart—is the scar left by that battle.

It turns out that to build a universe filled with complex elements, neutron stars, and eventually life, you cannot rely on the perfection of spheres. You need the chaos of the clam-shell. As our telescopes grow sharper and our simulations more powerful, we are likely to find that this asymmetry is the rule, not the exception, revealing a cosmos that is dynamic, lopsided, and spectacularly alive.