Prologue: The Purple Fog

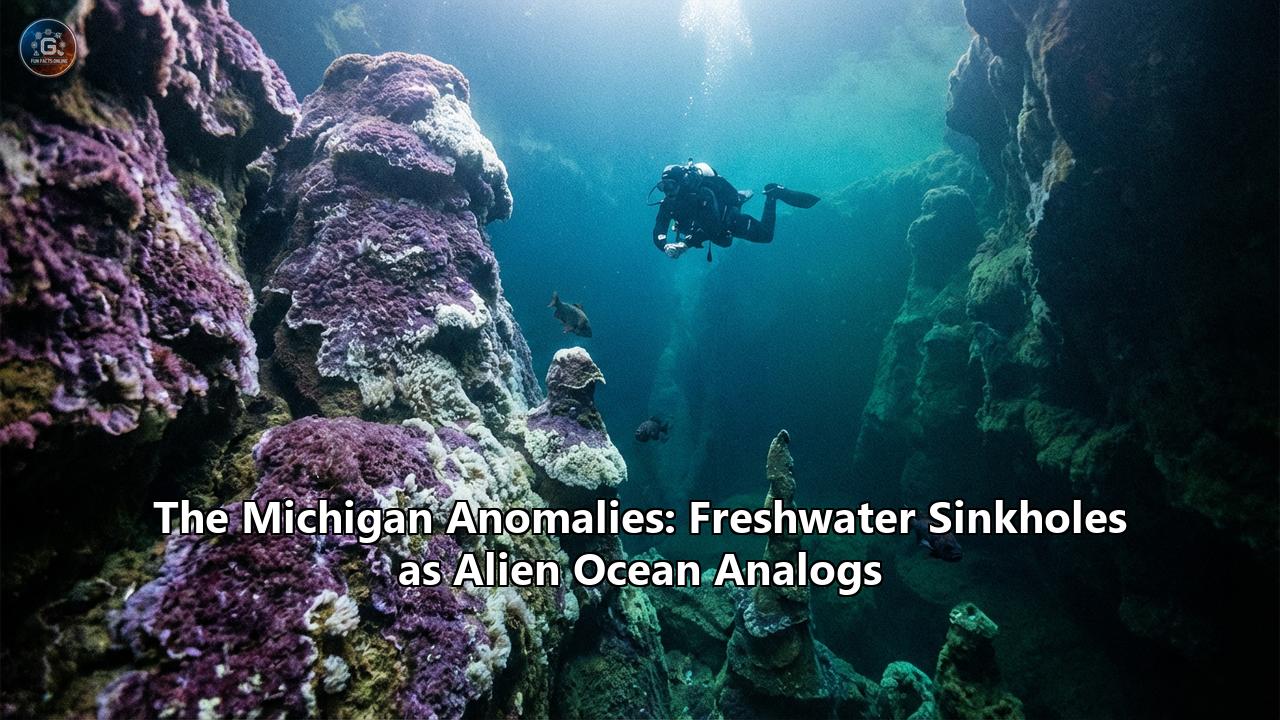

Eighty feet beneath the surface of Lake Huron, a diver descends into a world that should not exist. The water above is the familiar, crisp blue of the Great Lakes, chilly and relatively clear. But as the diver passes the rim of a submerged crater, the environment shifts violently. The temperature plummets. The water blurs, shimmering with a mixing haze known as a halocline—the visible boundary where buoyant fresh water meets a dense, heavy fluid rising from below.

Crossing this threshold, the diver enters a landscape that looks less like Michigan and more like a scene from science fiction. The lakebed, usually a drab expanse of silt and zebra mussels, is carpeted in a vibrant, pulsating mat of purple organic matter. Ridges and fingers of white, ghostly filaments wave in the current. The smell, even detectable through the regulator’s taste, is sharp and metallic—the undeniable stench of rotten eggs.

This is not a pollution site. It is the Middle Island Sinkhole, a natural "anomaly" within the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Here, in the heart of North America’s freshwater seas, lies a functioning ecosystem that mimics the conditions of Earth 2.5 billion years ago. Even more startling, it mimics the conditions scientists expect to find in the subsurface oceans of Jupiter’s moon, Europa, and Saturn’s moon, Enceladus.

These are the Michigan Anomalies. They are time capsules, they are alien laboratories, and they are currently rewriting our understanding of life’s resilience.

Part I: The Geologic Stage – A Rift in Time

To understand why an "alien ocean" exists in Lake Huron, we must look nearly a billion years into the past, to a geological event that almost destroyed the North American continent.

The Mid-Michigan Anomaly: The Scar That Shaped a Basin

The term "Michigan Anomaly" often refers to a specific geophysical feature: the Mid-Michigan Rift Anomaly. Approximately 1.1 billion years ago, the North American craton began to tear apart. Magma from the mantle surged upward, creating a massive rift system that stretched from Kansas, through Lake Superior, and down through the Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

For reasons geologists still debate, the rifting stopped. The continent did not split. Instead, the failed rift left behind a dense scar of igneous rock—basalt—buried deep beneath the surface. This dense rock creates a massive gravity high and magnetic anomaly that can be detected by sensors today. This "Mid-Michigan Anomaly" is the basement foundation of the state. As the heavy rift rock cooled, it sagged, creating a bowl-shaped depression in the crust.

Over the next several hundred million years, this bowl—the Michigan Basin—filled with shallow, tropical seas. Layer upon layer of sediment accumulated: sandstones, shales, and, crucially, massive deposits of carbonates (limestone and dolomite) and evaporites (salt and gypsum).

The Devonian Sea: Evaporites, Karst, and the "Swiss Cheese" Lakebed

During the Devonian period (roughly 419 to 359 million years ago), the seas that covered Michigan were rich in marine life and dissolved minerals. As these seas advanced and retreated, they left behind the Detroit River Group and the Salina Group—rock layers heavily laden with limestone, anhydrite, and gypsum.

These rocks are soluble. When groundwater moves through them, it dissolves the minerals, creating a landscape known as "karst." Karst is characterized by underground drainage systems, caves, and sinkholes. It is the geological equivalent of Swiss cheese.

In the Alpena region of Northeast Michigan, this karst formation is particularly aggressive. The bedrock here is fractured, allowing groundwater to permeate deep into the ancient, salty layers of the basin.

The Plumbing of the Abyss: How Ancient Aquifers Feed Modern Vents

The sinkholes in Lake Huron are not merely holes where the roof collapsed; they are active vents. The groundwater system in this region operates under significant hydraulic pressure. Rainwater falls on the mainland, seeps into the ground, and travels through the cracks and fissures of the karst aquifers.

As this water travels, it interacts with the Paleozoic evaporites—the ancient salts and gypsum left by the Devonian seas. It dissolves them, becoming laden with sulfate, chloride, and other minerals. By the time this groundwater reaches the coastline, it is no longer fresh. It is a brackish, sulfur-rich brine.

When this pressurized groundwater finds a weak point in the lakebed—a collapsed cave roof—it surges upward. This is the "venting" mechanism. The water emerging from the Middle Island Sinkhole is not lake water; it is ancient aquifer water, chemically distinct and carrying the molecular memory of a 400-million-year-old sea.

Part II: The Middle Island Sinkhole – A World Apart

While dozens of sinkholes scatter the lakebed of the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, the Middle Island Sinkhole (MIS) is the crown jewel of scientific research. Located just a few miles offshore, it sits at a depth of about 75 to 80 feet, making it accessible to advanced divers and small ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles).

Into the Arena: Anatomy of a Submerged Anomaly

The MIS is shaped like an hourglass or a figure-eight, consisting of two main chambers. The northern chamber is often referred to as the "Arena." It is a vast, bowl-shaped depression roughly 300 feet across. The walls of the sinkhole are sheer cliffs of limestone, dropping 20 to 30 feet from the surrounding lakebed.

Swimming over the rim is a disorienting experience. The surrounding lake floor is typical of the Great Lakes: sandy, covered in invasive quagga mussels, and relatively barren. Inside the sinkhole, the quagga mussels vanish. They cannot survive the chemistry of the pit.

At the bottom of the sinkhole lies the "Alcove," a specific venting point where the groundwater discharge is most vigorous. Here, the sediment is soft, dark, and fluffy—composed not of sand, but of meters-thick layers of decomposing organic matter and microbial biomass.

The Chemistry of the Deep: Sulfides, Anoxia, and the "Rotten Egg" Signal

The water inside the sinkhole is a chemical anomaly.

- Temperature: It remains a constant 45°F to 48°F (7°C to 9°C) year-round, regardless of whether the lake above is frozen or a balmy 70°F. This stability is a hallmark of groundwater feed.

- Oxygen: The vent water is hypoxic to anoxic (low to zero oxygen). Most fish, crustaceans, and mussels inadvertently entering the sinkhole will suffocate.

- Sulfur and Chloride: The water has high concentrations of sulfate and chloride, dissolved from the ancient evaporite rocks. Even more critical is the presence of hydrogen sulfide—the compound that gives the sinkhole its "rotten egg" smell and serves as the fuel for the ecosystem.

- Conductivity: Because of the dissolved salts, the water in the sinkhole is highly conductive—often ten times more conductive than the ambient lake water. This density difference creates the shimmering layer (halocline) that traps the vent water at the bottom, preventing it from mixing easily with the oxygen-rich lake water above.

The Hydrogeologic "Smoking Gun"

Scientists have used isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen to "fingerprint" the water in the sinkhole. The results confirm that this water is meteoric (rain/snow) in origin but has spent thousands of years traveling underground, reacting with the Detroit River Group formations. It is, effectively, fossil water pushing its way into the modern world.

Part III: The Time Machines – Biology of the Proterozoic

The most striking feature of the Michigan Anomalies is not the geology, but the biology. The Middle Island Sinkhole is carpeted in brilliant purple and white mats that look like velvet draped over the rocks. These are not plants; they are microbes.

The Purple and the White: A War for Photons and Chemical Energy

The ecosystem is dominated by two main types of bacteria, locked in a perpetual, slow-motion dance.

- Purple Cyanobacteria (Phormidium): These are photosynthetic, but they are not like the green algae found in the rest of the lake. They are adapted to low-light conditions and can perform anoxygenic photosynthesis (photosynthesis that does not produce oxygen) using sulfur compounds, or oxygenic photosynthesis when conditions permit. Their purple pigment allows them to harvest the specific wavelengths of light that penetrate the murky, sulfurous water.

- White Chemosynthetic Bacteria (Beggiatoa): These organisms do not need light at all. They are chemosynthetic, meaning they derive energy from chemical reactions—specifically, the oxidation of sulfur. They appear as white, filamentous "tufts" or hair-like structures.

The Diel Migration: The Daily Dance of the Microbes

For years, scientists were puzzled by the changing appearance of the mats. Sometimes they looked purple; other times, they looked white. Time-lapse photography revealed the answer: the mats are moving.

This phenomenon is known as diel vertical migration.

- Daytime: When sunlight filters down to the sinkhole floor, the purple cyanobacteria migrate to the top of the mat to capture photons for photosynthesis. They bury the white bacteria, turning the floor purple.

- Nighttime: When the sun sets, the photosynthetic advantage is lost. The white chemosynthetic bacteria, which rely on the sulfur rich water rising from below, migrate upward to access the sulfates and oxygen interface. They bury the purple bacteria, turning the floor white.

This "breathing" of the mat—purple by day, white by night—is a survival strategy in an environment where resources (light and chemicals) are stratified.

Oxygenating the Planet: How These Mats Explain the Air We Breathe

This daily dance has profound implications for Earth's history. Scientists believe that the Middle Island Sinkhole is a modern analog for the shallow seas of the Archean and Proterozoic Eons (2.5 to 4 billion years ago).

Back then, Earth’s atmosphere had almost no oxygen. The oceans were full of dissolved iron and sulfur. Cyanobacteria were the first organisms to "hack" photosynthesis to produce oxygen as a waste product. However, for millions of years, this oxygen didn't accumulate in the atmosphere; it was immediately consumed by iron and other chemicals in the water.

Research at the Middle Island Sinkhole suggests that the slowing of Earth’s rotation played a role in the Great Oxidation Event. Billions of years ago, Earth's day was only 6 hours long. The rapid day/night cycle might have prevented cyanobacteria from producing enough of a "surplus" of oxygen to escape the mats. As the Earth’s rotation slowed and days lengthened to 24 hours, the "purple phase" of the mat lasted longer, allowing for a net release of oxygen that eventually terraformed the planet. The Michigan sinkholes are essentially a working model of the engine that made Earth habitable.

Part IV: The Alien Ocean Connection – Astrobiology in the Great Lakes

If the sinkholes are time machines to Earth's past, they are also telescopes to the solar system's future. NASA and astrobiologists have zeroed in on the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary as a critical "analog site."

Europa and Enceladus: The Case for Subsurface Oceans

The two most promising targets for finding extraterrestrial life are Europa (a moon of Jupiter) and Enceladus (a moon of Saturn). Both are "Ocean Worlds." They have thick crusts of ice, beneath which lie global oceans of liquid water.

- Europa: Likely has a rocky seafloor in contact with the ocean, potentially creating hydrothermal vents.

- Enceladus: Has been observed venting plumes of water vapor containing silica and organic molecules, strong evidence of hydrothermal activity.

The problem is, we cannot easily access these oceans. We have to send robots to drill through miles of ice or swim through dark, high-pressure seas. We need to know what to look for and how to look for it.

Chemosynthesis: Life Without a Sun

On Earth, most life is based on a food web that starts with the sun (photosynthesis). On Europa, beneath 10 miles of ice, there is no sunlight. Life there would have to be chemosynthetic—relying on chemical energy, just like the white Beggiatoa bacteria in Lake Huron.

The Middle Island Sinkhole is a perfect "low-fidelity" analog. It combines:

- Anoxia: Like Europa's ocean, the sinkhole water is oxygen-poor.

- Sulfur Chemistry: The energy source is dissolved minerals, similar to what might be spewing from seafloor vents on icy moons.

- Cold Temperatures: The constant cold of the sinkhole mimics the thermal conditions of a sub-ice ocean (though Europa is liquid due to tidal heating, the water is still near freezing).

The "Analog" Concept: Why Michigan Matters to NASA

Why test in Michigan and not the deep ocean? Cost and accessibility. To test a robot in the deep ocean (like the Mariana Trench) costs millions of dollars and requires massive support ships. The Middle Island Sinkhole offers "deep ocean" chemistry at a depth of only 80 feet.

Scientists can deploy a prototype robot in the morning, monitor it from a small boat, and have it back in the lab by lunchtime if something breaks. This "rapid prototyping" environment is invaluable for developing the autonomous logic needed for a mission to Jupiter, where the communication delay makes real-time control impossible.

Part V: The Robotic Frontier – Preparing for the Outer Solar System

The Michigan Anomalies have become a playground for some of the most advanced marine robotics in the world.

Orpheus and the Hadal Class: Autonomous Navigation in the Dark

One of the stars of this technological testing is Orpheus, a class of Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) developed by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

Orpheus is designed to explore the Hadal Zone (the deepest trenches of Earth's ocean) and eventually, the oceans of Europa. Unlike traditional robots that rely on GPS (which doesn't work underwater) or heavy tethers, Orpheus uses Terrain Relative Navigation (TRN). It scans the seafloor with visual cameras and sonar, building a map in real-time and "recognizing" landmarks to navigate.

In the murky, featureless, and obstacle-rich environment of the sinkholes, Orpheus is trained to identify "science targets"—like the boundary between the bacterial mat and the rock—and make decisions about where to sample without human intervention.

Sampling the Unreachable: Suction, Coring, and DNA Sequencing

It’s not enough to just look; the robots must touch. The microbial mats in the sinkholes are delicate; if a thruster gets too close, the mat blows away. If a robotic arm grabs too hard, the sample is crushed.

Researchers in Thunder Bay have tested novel "suction samplers" that gently vacuum up the microbial mats, and "coring devices" that can take a plug of the sediment to analyze the layers of history. The goal is to miniaturize these labs so that a robot on Enceladus could suck up a sample, sequence its DNA (or alien equivalent), and beam the data back to Earth.

From Thunder Bay to Jupiter: The Technology Transfer

The data collected in Lake Huron helps calibrate the instruments for missions like Europa Clipper. While Clipper is an orbiter, future missions (like the Europa Lander) will need the landing and sampling logic being refined in terrestrial analogs. The spectral signatures of the purple sulfur bacteria in Lake Huron provide a baseline for what "biological color" might look like on a spectroscope scanning an alien ice crack.

Part VI: The Expanding Mystery – The Lake Michigan Anomalies

Just when scientists thought they had a handle on the Michigan sinkholes, a new mystery emerged.

The 2022 Discovery: Circles in the Sand

In 2022, and further investigated in 2024, researchers mapping the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary in Lake Michigan noticed something odd on their sonar. They were looking for a specific shipwreck, but instead, they found dozens of perfectly circular depressions in the lakebed.

These holes, located in about 450 feet of water (much deeper than the Alpena sinkholes), were previously unknown. Initial counts suggested nearly 40 of them, arranged in a line that seemingly tracked the edge of an ancient geological feature.

Comparing the Craters: Glacial Potholes or Active Vents?

Are the Lake Michigan holes the same as the Lake Huron sinkholes?

- Similarities: Both are circular, both are in the bedrock, and both appear in clusters.

- Differences: The Lake Michigan holes are deeper and darker. Initial ROV dives in August 2024 revealed they are indeed craters, but as of now, the vibrant purple mats of Huron haven't been confirmed in the same density.

There are two leading theories:

- Sinkholes: Like in Huron, these are collapsed karst features fed by groundwater. If so, they likely harbor similar chemosynthetic life, potentially even more adapted to the extreme pressure of the deeper lake.

- Glacial Scours: They could be ancient depressions carved by intense water falls or glacial moulins (water pouring down through a glacier) during the last Ice Age, which were then submerged.

If they are active vents, the "Michigan Anomaly" is not a localized freak occurrence but a systemic feature of the Great Lakes Basin—a vast, interconnected subterranean plumbing system that we are only just beginning to map.

The Future of Great Lakes Exploration: Lakebed 2030 and Beyond

Currently, we have better maps of the surface of Mars than we do of the Great Lakes floor. Only about 15% of the Great Lakes bottom has been mapped in high resolution. Initiatives like "Lakebed 2030" aim to map the entire system.

As this mapping progresses, scientists expect to find hundreds, perhaps thousands, more of these anomalies. Each one is a potential habitat for unique life, a potential source of groundwater input that affects lake levels, and a potential archaeological site where ancient humans might have camped when water levels were lower.

Epilogue: As Above, So Below

The Michigan Anomalies teach us a humbling lesson about exploration. We spend billions building telescopes to peer into the deepest reaches of space, and billions more building rockets to reach the moons of the outer planets. Yet, right here in the freshwater heart of North America, we have an alien world that was hidden in plain sight until the 21st century.

The sinkholes of Thunder Bay are more than just geological oddities. They are the intersection of Earth's deep past and humanity's future in space. They are the only place on the planet where you can dive into a Proterozoic ocean, watch bacteria hunt for sunlight, and see the testing ground for the robot that might one day tell us we are not alone in the universe.

When we look at the purple mats of Lake Huron, we are seeing the mechanism that gave us the air in our lungs. And when we eventually look at the black oceans of Europa, we may well see the reflection of the Michigan Anomalies staring back at us.

Reference:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2jj4wJHbMqU

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=okVRqLypENY

- https://www.discovermagazine.com/lake-hurons-middle-island-sinkhole-could-help-us-understand-earths-evolution-47429

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sX5DbIKHub0

- https://glos.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Costs-and-Approaches-for-Mapping-the-Great-Lakes.pdf

- https://underwaterscience.indiana.edu/upcoming-field-projects/thunder-bay-national-marine-sanctuary.html

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260412173_Choosing_between_strategies_for_designing_surveys_Autonomous_underwater_vehicles