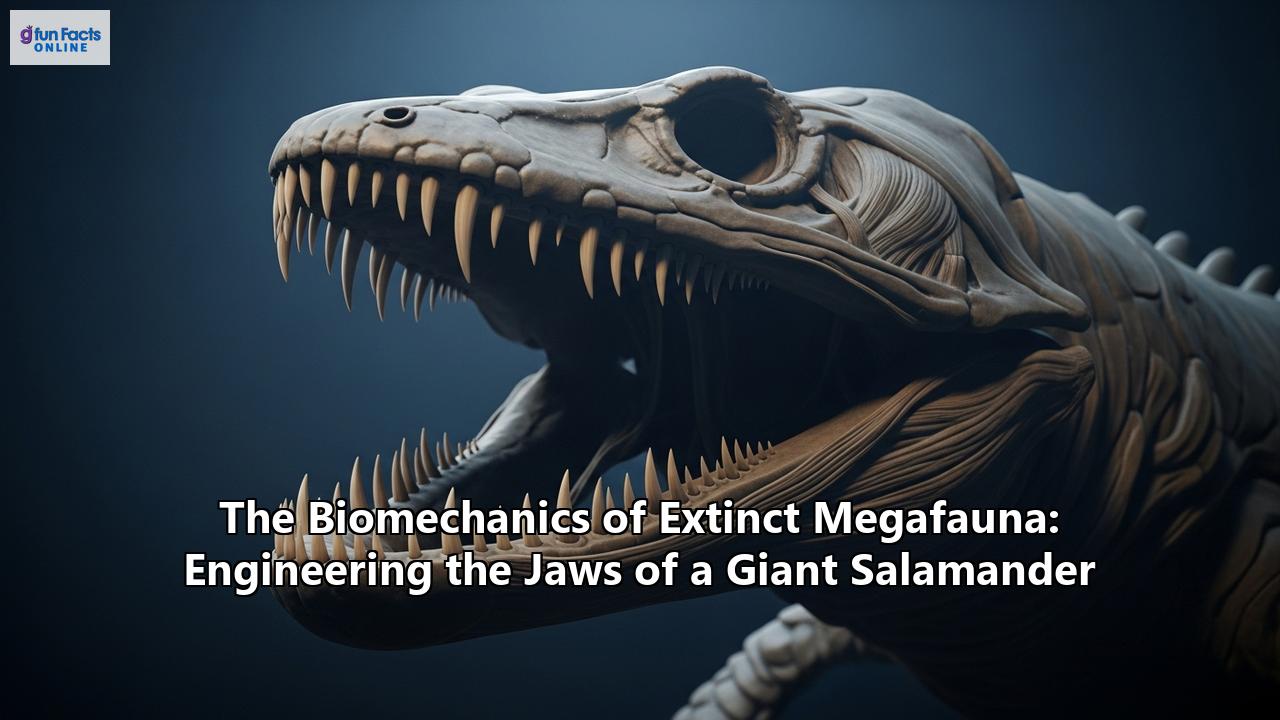

In the murky depths of prehistoric swamps and rivers, giants reigned. Not the thunderous dinosaurs that dominate our popular imagination, but colossal amphibians, creatures that blur the line between fish and land-dweller. Among these ancient behemoths were giant salamanders, some reaching the size of a small car. But how did these mega-amphibians hunt? What engineering marvels were hidden within their powerful jaws? Journey with us as we delve into the fascinating world of paleontological biomechanics to engineer the jaws of a giant salamander.

The Ghost in the Machine: Reconstructing Ancient Bite Forces

To understand the feeding mechanics of an animal that has been extinct for millions of years, paleontologists turn to a powerful computational tool: Finite Element Analysis (FEA). Originally developed for engineering complex structures like bridges and airplanes, FEA has become an indispensable method for testing the functional capabilities of extinct organisms. By creating detailed 3D models of fossil skulls, scientists can simulate the stresses and strains of different biting scenarios, effectively bringing these ancient predators back to life in a virtual environment.

This process begins with high-resolution CT scans of fossilized skulls, which are then used to create a digital blueprint. This virtual skull is then broken down into thousands, sometimes millions, of smaller, simpler geometric shapes, or "elements." By applying forces to this digital model—simulating the contraction of jaw muscles—and setting constraints, researchers can visualize how stress is distributed across the skull during a bite. These digital experiments allow paleontologists to test various hypotheses about how these animals fed without ever physically damaging the precious fossils.

A Tale of Two Giants: Metoposaurus and Prionosuchus

The world of extinct giant amphibians was diverse, with different species occupying various ecological niches. By examining the biomechanics of their jaws, we can uncover their hunting strategies. Two particularly fascinating examples are Metoposaurus and Prionosuchus.

Metoposaurus, a temnospondyl amphibian from the Late Triassic period, grew up to three meters long and possessed a massive, flat, parabolic skull with eyes positioned high on its head. FEA studies on Metoposaurus krasiejowensis have revealed a skull well-suited for a powerful bilateral bite. The stress distribution patterns suggest that these amphibians were likely ambush predators, lying in wait at the bottom of rivers and lakes before snapping up unsuspecting prey. The low stress levels in the front of the snout during a simulated straight-on bite indicate an efficient design for this type of predation.However, the story doesn't end there. The FEA models also show that the Metoposaurus skull could withstand the forces of a lateral, or sideways, strike. This suggests a more versatile hunting strategy than previously thought, allowing them to be both sit-and-wait predators and active hunters. Histological analysis of the cranial sutures—the lines where the skull bones meet—further supports this, revealing a predominance of interdigitated sutures that are excellent at handling compressive forces from biting.

In contrast, Prionosuchus, a truly colossal amphibian from the Permian period, stretched up to nine meters in length, making it one of the largest amphibians ever discovered. Its most striking feature was its long, slender snout, remarkably similar to that of a modern gharial. This gharial-like morphology strongly suggests a diet of fish. The elongated snout would have reduced water resistance, allowing for rapid jaw closure to snatch speedy aquatic prey. While detailed FEA studies on Prionosuchus are less common, its anatomy points to a specialized feeding mechanism distinct from the more robust-jawed Metoposaurus.

Lessons from the Living: The Chinese Giant Salamander

To better understand their extinct relatives, paleontologists often look to modern analogs. The Chinese Giant Salamander (Andrias davidianus), the world's largest living amphibian, provides invaluable insights into the feeding mechanics of these ancient giants. Like its prehistoric counterparts, the Chinese Giant Salamander is a formidable predator, feeding on a variety of prey including crustaceans, fish, and even small mammals.

Using FEA, scientists have modeled the bite of the Chinese Giant Salamander, revealing a surprisingly sophisticated feeding strategy. These studies show that the salamander's bite is most effective when attacking prey directly in front of it. However, it is also capable of a quick, asymmetrical strike to the side. Once prey is captured, it is often maneuvered to the front of the jaws for a more powerful, crushing bite. This two-step process—a quick initial capture followed by a stronger, disabling bite—may have been a common strategy among its extinct, larger-jawed relatives.

The Rise and Fall of the Amphibian Giants

The reign of the giant amphibians eventually came to an end. The extinction of many of these megafauna at the end of the Triassic period coincides with the rise of the first crocodilian forms. Biomechanical analyses comparing the skulls of these giant amphibians to early crocodiles suggest that they occupied different ecological niches. While superficially similar in their predatory lifestyles, subtle differences in their skull architecture, such as the lack of a secondary palate in amphibians, may have given the newly evolving crocodiles a competitive edge.

The study of the biomechanics of extinct megafauna is a window into lost worlds. By combining cutting-edge engineering techniques with traditional paleontology, we can resurrect the functional morphology of these incredible creatures. The jaws of the giant salamanders, from the powerful, all-purpose jaws of Metoposaurus to the specialized fish-trap of Prionosuchus, are a testament to the diverse and wondrous evolutionary paths taken by life on Earth. They are a reminder that the Age of Giants was not just about dinosaurs, but also about the incredible amphibians that lurked in the waters below.

Reference:

- https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/geo_facpub/1180/

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-paleontology/article/abs/review-of-paleontological-finite-element-models-and-their-validity/60BD063B98D0436030A2B362D9ED6F04

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263888016_A_review_of_paleontological_finite_element_models_and_their_validity

- https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.211357

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02724634.2016.1111225

- https://peerj.com/articles/2685/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5442151/

- https://www.keuper.us.edu.pl/02_Keuper-literature/Gruntmejer%20et%20al%202021_PJ.pdf

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31638728/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336730882_Cranial_suture_biomechanics_in_Metoposaurus_krasiejowensis_Temnospondyli_Stereospondyli_from_the_upper_Triassic_of_Poland

- https://answersresearchjournal.org/fossil-baramins-noahs-ark-amphibians/

- https://www.palass.org/sites/default/files/media/publications/palaeontology/volume_34/vol34_part3_pp561-573.pdf

- http://www.storagetwo.com/blog/2017/1/crocodiles-a-curious-case-of-repeating-evolution

- https://www.uab.cat/web/news-detail/how-the-world-s-largest-salamander-feed-1345680342044.html?articleId=1345683918994

- https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/532555

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_giant_salamander

- https://www.uab.cat/web/news-detail/crocodile-or-salamander-the-role-of-giant-amphibians-in-the-ecosystems-of-the-triassic-period-1345721847335.html?noticiaid=1345709485681