In the quiet, dusty archives of deep time, where the chapters of life are written in stone, there are occasional discoveries that do not merely add a footnote to history but threaten to tear out entire pages and rewrite them. For decades, paleontologists have hunted for the ghosts of the Cambrian Explosion—that frenetic biological Big Bang occurring over half a billion years ago, when life on Earth seemingly decided to try every possible shape and survival strategy at once. Among the most elusive of these phantoms has been the ancestor of the mollusks. Today, the phylum Mollusca is a biological titan, boasting over 85,000 living species ranging from the microscopic snail to the colossal squid, from the brainless clam to the tool-using octopus. But their origins have remained shrouded in a fog of poor preservation.

Then came Shishania aculeata.

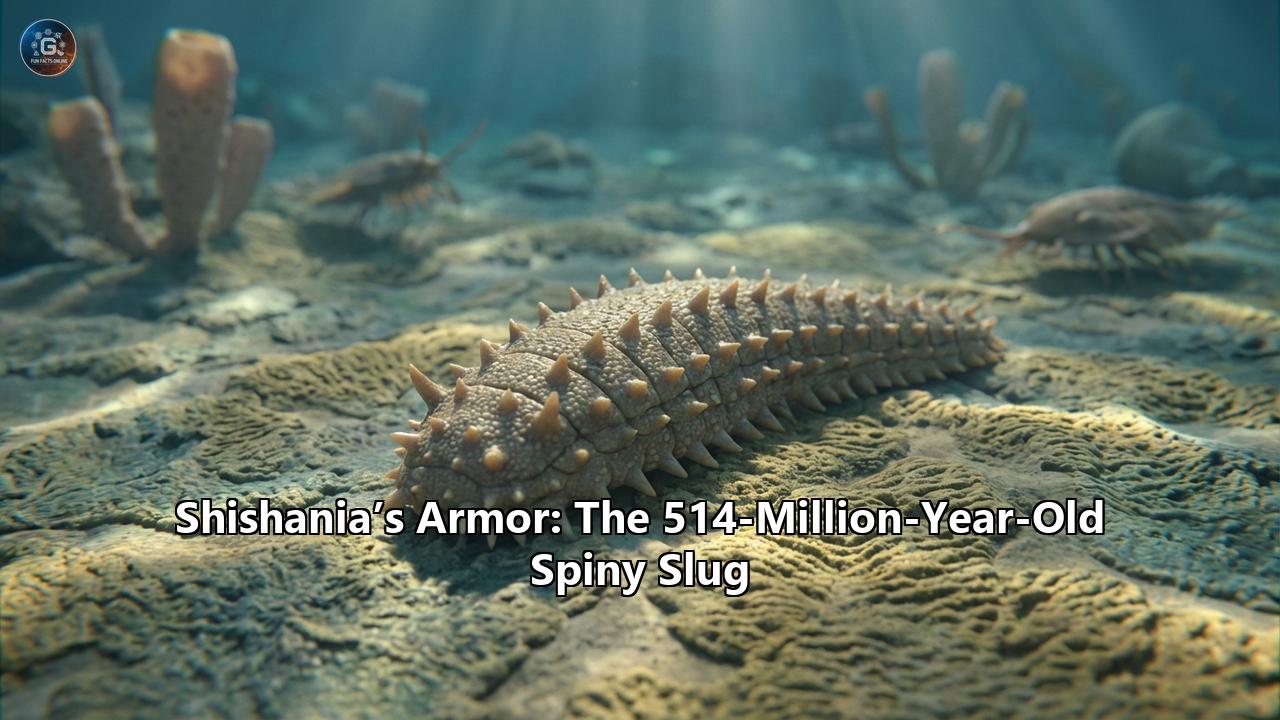

Discovered in the lush, fossil-rich hills of China’s Yunnan Province, this creature—a 514-million-year-old spiny oddity—burst onto the scientific scene in 2024 as the long-lost "missing link" of the mollusk world. It was hailed as a primitive, shell-less, armored slug that finally bridged the evolutionary gap between slimy worms and hard-shelled snails. It was the "spiny grandmother" of all mollusks, a creature that proved armor came before the shell.

But as is often the case in the high-stakes world of paleontology, the stone had not yet finished speaking. By 2025, new analyses began to suggest that Shishania might be something else entirely—a master of disguise that had fooled the world’s experts through a phenomenon known as "fossil origami."

This is the comprehensive story of Shishania aculeata, a creature that looked like a rotting plastic bag but held the secrets of animal evolution in its microscopic spines. It is a tale of discovery, misinterpretation, and the relentless self-correction of science, set against the backdrop of an alien ocean half a billion years ago.

Part I: The Discovery of the "Rotting Plastic Bag"

The story begins in the eastern Yunnan Province of China, a region that has become a Mecca for paleontologists. Here lies the Guanshan Biota, a geological treasure trove dating back to the Cambrian Series 2, Stage 4—approximately 514 million years ago. While the more famous Chengjiang Biota offers a window into slightly older oceans, the Guanshan preserves a marine world in transition, a time when the initial burst of the Cambrian Explosion was settling into complex ecosystems.

It was here that Guangxu Zhang, a doctoral student from Yunnan University, was sifting through slabs of shale. The work of a fossil hunter is often defined by hours of monotony punctuated by seconds of adrenaline. But when Zhang first laid eyes on the specimen that would become Shishania, there was no adrenaline. There was only confusion.

The fossil didn't look like a majestic trilobite or a fearsome predator like Anomalocaris. It looked, in Zhang’s own words, like "a rotting little plastic bag." It was a flat, amorphous blob, roughly three centimeters long (about 1.2 inches), unremarkable to the naked eye. It would have been easy to discard it as a piece of ancient debris, a smudge of organic matter with no story to tell.

But Zhang persisted. He placed the "plastic bag" under a magnifying glass, and the smudge resolved into something spectacular. The surface of the creature was not smooth; it was covered in a dense forest of tiny, conical spines. It was armored.

Recognizing the potential significance, Zhang teamed up with Luke Parry, a paleontologist at the University of Oxford renowned for his work on early Cambrian life. Together with colleagues from the University of Bristol and Yunnan University, they launched a detailed investigation into this spiny enigma. They named it Shishania aculeata. The genus name, Shishania, honored Shishan Zhang, a legendary Chinese paleontologist who had pioneered the study of Cambrian strata in the region. The species name, aculeata, is Latin for "prickly"—a fitting moniker for a creature that looked like a flattened durian fruit or a hedgehog that had been run over by a steamroller.

Part II: The Anatomy of an Enigma

To understand why Shishania caused such a stir, we must delve into its anatomy. The preservation of these fossils was nothing short of miraculous. While the hard shells of clams and trilobites fossilize easily, soft tissues usually rot away long before they can turn to stone. Shishania was soft-bodied, yet the fine mud of the Guanshan sea floor had entombed it rapidly, preserving even the most delicate structures.

The Spines (Sclerites): Natural 3D PrintingThe most defining feature of Shishania was its armor. The creature’s dorsal side (its back) was carpeted with thousands of hollow, cone-shaped spines called sclerites. Unlike the solid limestone spines of modern sea urchins, Shishania’s spines were organic, made of chitin—the same crunchy material that forms the exoskeletons of insects, crabs, and shrimp today.

Using advanced electron microscopy, the research team peered inside these ancient spines. What they found was a marvel of biological engineering. The spines were not solid cones; they contained an internal system of microscopic canals, each less than a hundredth of a millimeter in diameter.

This microstructure was a "smoking gun" for how the animal built its armor. The canals indicated that the spines were secreted at their base by microvilli—tiny, finger-like extensions of cells that increase surface area. In the human body, microvilli line our intestines to help absorb nutrients. In Shishania, they acted like the nozzles of a biological 3D printer, extruding chitin layer by layer to build a protective spike. This method of fabrication is incredibly specific and is seen today in the bristles (chaetae) of annelid worms and, crucially, in the shell secretion mechanisms of some primitive mollusks.

The Body PlanBeneath this coat of armor, Shishania appeared to be a bilaterally symmetrical slug. The 2024 study identified a "girdle"—a fleshy rim surrounding the body—and, most importantly, a "foot."

The foot is the hallmark of the mollusk. It is the muscular sole that a snail uses to glide along a leaf, the digging tool of a clam, and the modified tentacles of a squid. In the Shishania specimens that were fossilized upside down (ventral side up), the researchers interpreted a broad, muscular structure running down the center of the body. To the eyes of the 2024 team, this was the clincher. Shishania had the armor of a worm-like ancestor but the locomotion of a mollusk. It was a walking—or rather, crawling—fortress.

Part III: The Mollusk Hypothesis (2024)

When the initial paper was published in Science in August 2024, it was hailed as a breakthrough. To understand why, one must look at the chaotic family tree of the Lophotrochozoa, the super-phylum that includes mollusks, annelid worms, and other invertebrates.

For decades, zoologists have debated what the first mollusk looked like. Did it have a shell? Was it worm-like? The prevailing theory was the "Aculifera" hypothesis, which suggested that the ancestor of all mollusks was covered in spines (spicules) rather than a solid shell. According to this view, the solid shells of clams and snails evolved later, formed by the fusion of these spines.

Shishania fit this theory like a key in a lock.- Chronology: At 514 million years old, it predated many of the clear, shelled mollusks.

- Morphology: It possessed the "aculiferan" body plan—spiny top, naked bottom with a foot.

- Deep Homology: The microscopic canals in the spines provided a link to annelid worms. It suggested that the bristles of an earthworm and the spines of a chiton (a primitive modern mollusk) shared a deep genetic origin. Shishania was the bridge.

The narrative was compelling: Shishania was a "stem-mollusk." It represented a lineage that branched off before the invention of the true shell. It wandered the Cambrian seafloor, grazing on algae with a radula (a rasping tongue, though not preserved, was inferred), protected from predators by its chitinous spikes. It was the great-aunt of the octopus, a humble, spiny slug that started a dynasty.

The scientific community celebrated. The "plastic bag" had given face to a ghost lineage. Art reconstructions showed Shishania crawling over sponges, a prickly pancake in a primordial sea.

But science is rarely static. While the ink was drying on the textbooks, other researchers were taking a second, closer look.

Part IV: The Twist – The Chancelloriid Connection (2025)

By May 2025, less than a year after the initial fanfare, the narrative began to unravel. A new study, led by researchers including Jie Yang and Martin Smith, published in Science (and discussed in Science Advances), dropped a bombshell. Shishania, they argued, was not a mollusk at all.

It was a chancelloriid.

To the uninitiated, this might sound like a trivial taxonomic quibble. But in the context of Cambrian paleontology, it is the difference between calling a bat a bird or a mammal.

What is a Chancelloriid?Chancelloriids are among the most bizarre and problematic groups of the Cambrian. Often described as "cactus sponges," they were balloon-shaped, sessile (immobile) animals that lived anchored to the seafloor. They had bag-like bodies covered in star-shaped spines. They look somewhat like sponges but are much more complex, possibly related to the ancestors of all animals with nervous systems. They had no foot, no eyes, and certainly did not crawl.

The Evidence for ReclassificationThe 2025 team re-examined the Shishania fossils and compared them with another ambiguous Cambrian fossil, Nidelric. Their analysis dismantled the mollusk hypothesis piece by piece:

- The "Foot" Illusion: The "muscular foot" identified in 2024 was re-interpreted as a taphonomic artifact—a "fossil ghost." Taphonomy is the study of how organisms decay and fossilize. The 2025 team argued that when a balloon-like chancelloriid is crushed flat by millions of years of sediment, the folding of its body wall can create a ridge that looks like a foot but is actually just a crease. They called this "fossil origami."

- The Spines: While Shishania’s spines were hollow and chitinous, the new study pointed out that they lacked the specific arrangement seen in true mollusks. Instead, they closely resembled the simplified, spine-like structures of certain chancelloriids. The "canals" were interpreted not as specialized secretion channels unique to mollusks, but as a more general feature of primitive sclerite growth.

- The Lifestyle: If Shishania was a chancelloriid, it wasn't a mobile slug. It was a stationary sack, sitting on the mud, filtering water or absorbing nutrients through its body wall. The "plastic bag" description by Zhang turned out to be more accurate than anyone realized—it was essentially a living, spiny bag.

The reclassification linked Shishania to Nidelric, another fossil that had bounced between being called a sponge and a microscopic mystery. The 2025 study suggested that Shishania, Nidelric, and chancelloriids formed a distinct evolutionary group that flourished in the Cambrian and then went extinct, leaving no direct descendants. They were evolutionary experiments—dead ends in the tree of life.

Part V: Why Shishania Matters, Regardless of What It Is

The debate between the "Spiny Slug Mollusk" camp and the "Cactus Sponge" camp is ongoing, a testament to the scientific method. But whether Shishania is the grandmother of the snail or a dead-end cactus-balloon, its importance remains undiminished. It teaches us profound lessons about the history of life on Earth.

1. The Innovation of ArmorWhether mollusk or chancelloriid, Shishania showcases the Cambrian arms race. 514 million years ago, predators were evolving eyes, claws, and jaws. In response, soft-bodied prey had to adapt. Shishania evolved armor. The development of chitinous spines was a high-tech solution for the time. It was lightweight, tough, and energetically cheaper to produce than heavy mineral shells. This suggests that the early Cambrian seas were a dangerous place, where "get spiny or get eaten" was the law of the land.

2. The Complexity of the "Stem" Shishania illustrates the concept of "stem groups." In evolution, before you get a "crown" group (like modern mollusks with all their defining features), you have a "stem" group—organisms that have some but not all of the features. If Shishania is a stem-mollusk, it tells us that spines came before shells. If it is a stem-chancelloriid, it tells us that this extinct group was more diverse than we thought, experimenting with slug-like shapes (or shapes that crush into slug-like fossils). 3. The Miracle of Micro-PreservationThe fact that we are arguing about the function of microvilli in a creature that died 514 million years ago is staggering. The Guanshan fossils preserve cellular details. We can see the plumbing of ancient life. This level of detail allows us to test hypotheses about deep homology—the idea that the genetic blueprints for body parts (like spines) are shared across vast distances of evolutionary time. Even if Shishania isn't a mollusk, the machinery it used to make its spines is likely the same machinery inherited by the ancestors of mollusks and annelids, pointing to a shared "toolkit" in the very first animals.

4. The Cautionary Tale of TaphonomyThe reinterpretation of Shishania’s foot serves as a humbling reminder of the difficulty of paleontology. We are trying to reconstruct a 3D animal from a 2D smear of chemicals. The "fossil origami" effect shows how easily the geological crushing process can mimic biological structures. It forces scientists to be skeptical, to look for multiple lines of evidence, and to constantly revise their models.

Part VI: A World of Weird Wonders

To fully appreciate Shishania, we must visualize its world. The Guanshan Biota was a shallow, tropical sea. The water was warm and teeming with life.

Swimming overhead were radiodonts, the cousins of Anomalocaris, looking like swimming lobsters with circular mouths. On the seafloor, trilobites scuttled, kicking up clouds of mud. Brachiopods (lamp shells) filtered the water. And there, amidst the chaos, sat (or crawled) Shishania.

If the mollusk theory holds, imagine a flat, spiny slug, inching along a bacterial mat. It encounters a sponge and rasps away at it. A predator casts a shadow, and Shishania hunkers down, presenting a bed of thorns.

If the chancelloriid theory holds, imagine a field of spiny balloons, gently swaying in the current. They look like strange underwater cacti. Shishania is one of them, perhaps slightly flattened or adapted for a specific niche, filtering organic particles from the soup of life.

Part VII: The Future of the Past

The story of Shishania aculeata is far from over. Future discoveries in the Yunnan Province could yield a "Rosetta Stone" specimen—perhaps one preserved in 3D, or one showing internal organs that clearly distinguish between a mollusk gut and a chancelloriid cavity.

Until then, Shishania remains a Schrödinger’s Fossil: simultaneously a slug and a sponge, a ancestor and an evolutionary dead end.

Key Takeaways for the Science Enthusiast:- Age: 514 Million Years Old (Cambrian Stage 4).

- Location: Eastern Yunnan Province, China (Guanshan Biota).

- Size: ~3 cm long.

- Appearance: Flattened, covered in hollow chitinous spines (sclerites).

- The Controversy:

Hypothesis A (2024): A stem-mollusk, a spiny slug with a foot, proving spines evolved before shells.

Hypothesis B (2025): A chancelloriid, a sessile balloon-animal, with the "foot" being a preservation artifact.

- Significance: It reveals the early evolution of animal armor and the difficulties of interpreting the soft-bodied fossil record.

In the end, Shishania aculeata is a testament to the richness of Earth’s history. It reminds us that for every animal we know today, there were thousands of experiments that nature ran and discarded. Some became the kings of the ocean; others became strange, spiny ghosts trapped in the rock, waiting half a billion years for a curious ape to dig them up, call them a "rotting plastic bag," and then spend years arguing about what they actually were. And in that argument lies the beauty of science—the ceaseless, prickly quest for truth.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shishania

- https://www.popsci.com/science/spiny-slug-mollusk/

- https://connectsci.au/news/news-parent/2304/Half-a-billion-year-old-spiny-slug-fossil-reveals

- https://www.sci.news/paleontology/shishania-aculeata-13892.html

- https://scitechdaily.com/completely-different-discovery-of-strange-514-million-year-old-slug-rewrites-our-understanding-of-sea-creatures/

- https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2024-08-02-half-billion-year-old-spiny-slug-reveals-origins-molluscs

- https://www.labrujulaverde.com/en/2024/08/new-fossil-discovery-reveals-the-ancestry-of-mollusks-as-armored-spiny-slugs/

- https://www.earth.com/news/mollusks-evolution-shishania-aculeata-spiny-armor-no-shells-500-million-years-ago/

- https://www.techexplorist.com/500-million-years-old-slug-reveals-origins-molluscs/86843/

- https://news.exeter.ac.uk/faculty-of-environment-science-and-economy/half-a-billion-year-old-spiny-slug-reveals-the-origins-of-molluscs/

- https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/insects-invertebrates/half-a-billion-year-old-slug-found-in-china

- https://news.sky.com/story/half-a-billion-year-old-slug-with-spikes-reveals-origins-of-molluscs-13188853

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/article/2024/aug/01/love-child-of-slug-and-hedgehog-fossils-may-shed-light-on-early-mollusc-ancestors

- http://www.ecns.cn/news/society/2024-08-04/detail-iheeyrtw7456277.shtml