The waters of the Øresund have always been a graveyard of history, a restless, shifting archive of timber and iron where the ambitions of kings and the fortunes of merchants lie buried beneath the grey silt. For centuries, the strait separating Denmark and Sweden has been one of the busiest maritime arteries in the world, a choke point of commerce and conflict. But on a cold, steel-grey morning in late 2025, the Sound gave up a secret that has rewritten the history books of the Middle Ages. They call it the "Copenhagen Colossus." Technically, it is known as Svælget 2, but to the team of marine archaeologists who have spent the last eighteen months battling currents, mud, and the immense pressure of history to bring it to the surface, it is simply "The Beast."

This is not just another shipwreck. This is the raising of a leviathan, a resurrection of wood and ambition that has not seen the sun since the days of Queen Margrethe I. It is the largest medieval cog ever discovered—a "super ship" of the 15th century that rivals the modern giants of the Maersk fleet in its relative scale and significance. Its discovery during the preliminary surveys for the massive Lynetteholm artificial island project has turned a routine construction survey into the most significant maritime archaeological event since the raising of the Vasa.

For the first time, the full story of this extraordinary vessel—and the Herculean effort to raise it from its watery tomb—can be told.

Part I: The Shadow in the Silt

The discovery of the Copenhagen Colossus was, in many ways, an accident of progress. Copenhagen is a city that is constantly growing, pushing its boundaries outward into the sea. The Lynetteholm project, a controversial plan to build a vast artificial peninsula to protect the city from storm surges and house its growing population, required extensive seabed analysis. The area, known as Svælget (The Throat), is a deep channel notorious for its strong currents—a place where ships have struggled for centuries.

In the summer of 2024, side-scan sonar surveys picked up an anomaly. It wasn't the jagged, chaotic signature of a scattered wreck, nor was it the smooth hummock of a sandbank. It was a massive, coherent shape, looming out of the flat seabed like the spine of a sleeping dragon.

"We see anomalies all the time," says Dr. Otto Uldum, the lead archaeologist from the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, who has spearheaded the excavation. "Usually, they are rocks, lost shipping containers, or clumps of modern debris. But this… this had geometry. It had structure. And it was huge."

When the first divers descended, the visibility was poor, the water a murky green soup of algae and stirred-up sediment. But as they neared the bottom, the gloom parted to reveal a wall of oak. It wasn't just a few scattered planks; it was a hull, standing proud of the seabed, rising nearly six meters from the sand.

"It was like swimming up to the side of a building," recalls Sarah Jensen, one of the lead divers on the initial reconnaissance team. "I put my hand out and touched the wood. It was hard, solid. It didn't feel like something that had been down there for six hundred years. It felt like it was waiting."

As the team mapped the site, the dimensions of the find began to sink in. The ship measured nearly 30 meters (approx. 100 feet) in length and 9 meters in width. In the context of the Middle Ages, this was a monster. Most cogs—the workhorses of the Hanseatic League—were perhaps 15 to 20 meters long. This vessel was a titan, built to carry 300 tons of cargo in a single voyage. To put that in perspective, it could swallow the load of ten ordinary merchant ships of its day. It was the "Emma Maersk" of the 15th century, a vessel designed to dominate the bulk trade routes of Northern Europe.

They named it Svælget 2, after the channel where it rested, but the media quickly dubbed it the "Copenhagen Colossus." The name stuck.

Part II: The Anatomy of a Titan

What makes the Copenhagen Colossus so significant is not just its size, but its preservation. The Baltic Sea and the Øresund are unique in the world of marine archaeology. The brackish water is too low in salinity to support the Teredo navalis—the shipworm that devours wood in saltier oceans. As a result, shipwrecks in this region can survive for centuries in a state of suspended animation, their timbers as sound as the day they were felled.

The Colossus is a cog, the iconic vessel of the medieval north. With its flat bottom, high sides, and single square sail, the cog was the machine that built the Hanseatic League, the powerful trading confederation that dominated the Baltic and North Sea trade. But the Colossus challenges everything we thought we knew about these ships.

The Hull and ConstructionThe hull is a masterpiece of medieval engineering. Dendrochronological analysis (tree-ring dating) of the timbers has dated the construction to around 1410. The wood tells a story of international supply chains that rivals modern logistics. The massive planks of the hull are Polish oak, likely floated down the Vistula River to the shipyards of Gdańsk or Lübeck. The curved frames, however, are made of Dutch timber. This ship was a cosmopolitan creation, born of a Europe that was far more interconnected than we often give it credit for.

Unlike the sleek, flexible Viking longships that came before it, the Colossus was built for brute force and capacity. It was constructed "shell-first," with the planks overlapping in the clinker style, held together by thousands of iron rivets, before the internal framing was inserted. This gave the hull a tremendous elasticity and strength, allowing it to groan and flex in the heavy swells of the North Sea without breaking.

The Floating FortressOne of the most spectacular finds was the sterncastle. On most cog wrecks, the upper works are the first to be destroyed, smashed by storms or ice. But on the Colossus, the sterncastle—a raised platform at the back of the ship used for defense and command—was found partially intact. It stood like a tower on the seabed, its intricate joinery still visible.

"This changes our understanding of naval architecture," explains Dr. Uldum. "We see here a transitional form. It has the defensive capabilities of a warship but the hold of a merchantman. In 1410, piracy was rampant. The Vitalienbrüder (Victual Brothers) were terrorizing the Baltic. A ship this rich, this large, would have been a floating fortress. It didn't just carry cargo; it projected power."

The Galley and the HearthPerhaps the most humanizing discovery was the galley. Amidships, divers found a brick-built hearth. In the 15th century, fire was the greatest danger on a wooden ship, and cooking was usually done on a bed of sand or in a firebox. But the Colossus had a dedicated, structural brick oven. This implies a level of comfort and sophistication previously unseen. It suggests that this ship was intended for long, difficult voyages where hot food was not a luxury, but a necessity for crew survival. Around the hearth, they found the ghostly remnants of the crew’s last meal: a copper cauldron, a wooden tray worn smooth by use, and animal bones that hint at a diet of salted pork and fish.

Part III: The World of 1410

To understand the Colossus, we must understand the world that built it. The year is 1410. The Kalmar Union—the unified kingdom of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden—is a reality, forged by the iron will of Queen Margrethe I. She is the most powerful woman in Europe, ruling an empire that stretches from Greenland to Finland. But her empire is locked in a cold war with the Hanseatic League, the German merchant princes who control the flow of money and goods in the Baltic.

The Colossus was likely a pawn in this high-stakes game. Was it a Hanseatic vessel, built to flood the markets of Bruges and London with Baltic timber and grain? Or was it a royal ship, a part of King Erik of Pomerania’s fleet, designed to bypass the Hansa and assert Danish control over the Sound?

The size of the vessel points to a shift in the global economy. For centuries, trade had been focused on luxury goods—furs, amber, spices, silk—items that could be carried in small bundles on light ships. But by the 1400s, Europe was hungry for bulk. The growing cities of England and the Low Countries needed timber for houses, bricks for cathedrals, and vast quantities of salted herring to feed their populations. The Colossus was the solution. It was the super-tanker of its age, designed to move mountains of raw materials.

The Cargo MysteryOne of the most tantalizing mysteries of the excavation was the hold. A ship of this size should have been packed to the gunwales. Yet, when the archaeologists excavated the silt from the belly of the beast, they found… emptiness.

There were no stacks of timber, no barrels of wine, no bales of wool. Just the personal effects of the crew—shoes, combs, rosary beads. This has led to two prevailing theories. The first is that the ship was sailing in ballast, empty and high in the water, perhaps returning from a delivery when disaster struck. A high-riding cog is notoriously unstable; a sudden squall could have capsized it in moments.

The second theory is darker. The Sound was a gauntlet of tolls and taxes. Did the ship run aground while trying to smuggle goods past the customs agents at Helsingør? Or was it stripped? If the ship sank in shallow water (the depth at the site is only about 13-15 meters), it is possible that in the immediate aftermath of the sinking, salvage teams from the 15th century stripped it clean of its valuable cargo, leaving only the hull behind.

Part IV: The Sinking

How does a ship this size, a masterpiece of its age, end up on the bottom of the sea? The hull offers clues, but no definitive answers. There is no sign of fire—unlike the Gribshunden, King Hans’s flagship which blew up and sank nearby in 1495. There is no massive damage to the keel suggesting a catastrophic grounding at speed.

The leading theory, supported by the position of the wreck, is a "side-on" sinking. The ship was found lying on its starboard side, which is why that side is so perfectly preserved up to the deck, while the port side has largely eroded away. This suggests a sudden capsize.

"Cogs were tubby, high-sided ships," says naval architect Jens Andersen, who is consulting on the project. "They were brilliant load-carriers, but they were not weatherly. If the Colossus was empty, riding high, and was hit broadside by a sudden squall coming off the land—a common occurrence in the Sound—it could have rolled over before the crew even had time to cut the sheets."

We can imagine the scene: a grey, blustery afternoon in the Sound. The giant ship is beating upwind, struggling against the current. The crew is tired, cold. Suddenly, the wind shifts. The massive square sail catches aback. The ship heels, further and further. The ballast shifts. And in a terrifying, groaning rush, the horizon becomes vertical, and the freezing water of the Øresund pours in through the open hatchways. It would have been over in minutes.

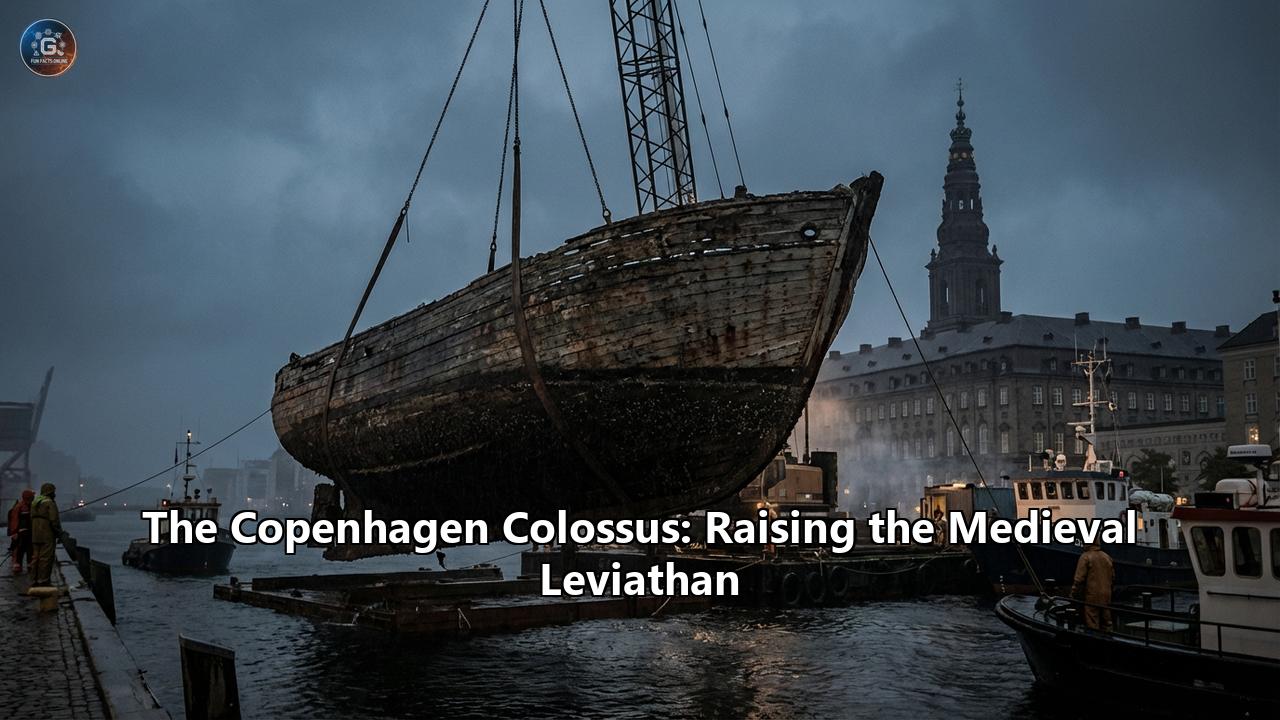

Part V: The Resurrection – Raising the Beast

Finding the Colossus was one thing; bringing it back to the world was another. The decision to raise the ship was not taken lightly. In the world of archaeology, "in situ" preservation (leaving it where it is) is usually preferred. Raising a ship is expensive, risky, and commits the finder to decades of conservation work.

But the Colossus was in the way. It lay directly in the footprint of the perimeter for the new Lynetteholm peninsula. It had to move, or be destroyed. And so, the project to raise it began—a logistical nightmare that would require the most advanced marine engineering available.

The "Cheese Slicer" MethodThe sheer size of the Colossus made lifting it in one piece impossible. The weight of the waterlogged oak, combined with the sediment filling every crack, was estimated at over 500 tons. The structural integrity of the hull, while good for its age, would never withstand the stress of a single-point lift. The Vasa was lifted whole, but it had a wire cage built around it and was in deeper, calmer water. The Colossus was in a high-current zone.

The team opted for a radical and controversial solution: they would cut the ship.

Using a diamond-wire cutting system—essentially a giant, underwater cheese slicer—the team planned to slice the hull into manageable sections, each supported by a steel cradle, and lift them individually. This sounded barbaric to purists, but Dr. Uldum defended the choice.

"It is surgery," he told the press in 2025. "We are not smashing it. We are making precise, calculated incisions that will allow us to disassemble the ship and reassemble it in the museum, plank by plank. It is the only way to save it."

The OperationThe recovery operation, documented in the gripping DR TV series Gåden i Dybet ("The Mystery in the Deep"), was a race against time and weather. The winter of 2025 was harsh. Divers worked in near-freezing water, battling currents that threatened to drag them away from the wreck site.

The most dramatic moment came in November 2025, during the lifting of the midsection containing the brick hearth. As the crane took the strain, the sensor arrays screamed warnings. The suction of the mud was refusing to let go. For an agonizing twenty minutes, the crane strained, the cables singing in the wind, the massive section of hull hovering just inches off the seabed. Then, with a dull boom that could be heard through the hull of the dive ship, the mud gave way. The Colossus was free.

Section by massive section, the ship broke the surface. For the first time in 600 years, the oak planks dried in the Copenhagen air. They were immediately wrapped in plastic and sprayed with water to prevent shrinking, then transported on barges to the conservation facility at the National Museum in Brede.

Part VI: The Treasures of the Deep

While the hull is the star, the small artifacts recovered from the sediment have provided a poignant window into the souls of the men who sailed her.

The Sailor’s ShoeOne of the first items found was a leather shoe, remarkably intact. It is a simple, turn-shoe design, worn at the heel. It tells of a sailor who walked the deck for thousands of hours, a man of limited means but practical skill.

The Merchant’s CombA fine boxwood comb, double-sided, was found near the sterncastle. This was not a peasant’s tool. It belonged to someone who cared about their appearance—perhaps the captain, or a merchant passenger. It suggests that life aboard the Colossus had a hierarchy, a social structure mirrored in the very layout of the ship.

The Tally StickPerhaps the most commercially significant find was a "tally stick"—a piece of wood with notches carved into it. In an illiterate age, this was the spreadsheet. Each notch represented a transaction, a debt, or a unit of cargo. Deciphering the code of this stick could reveal exactly what the Colossus was trading in its final days.

The RiggingMiraculously, elements of the rigging survived. The "deadeyes"—wooden blocks used to tension the shrouds—were found still attached to the remnants of the ropes. This is unheard of. Rigging is usually the first thing to rot. These survivals allow archaeologists to reconstruct exactly how these massive sails were managed. It confirms that the cog used a "bowline" system to sail closer to the wind than previously thought, challenging the idea that these ships could only sail with the wind behind them.

Part VII: The Conservation Challenge

Now that the Colossus is on dry land, the real battle begins. The conservation of 300 tons of waterlogged wood is a scientific marathon. The enemy is cellular collapse. The cell walls of the ancient oak have been replaced by water. If that water evaporates, the cells will collapse, and the wood will shrink, crack, and turn to dust.

The solution is PEG—polyethylene glycol. For the next ten to fifteen years, the timbers of the Colossus will be showered with a waxy solution that will slowly replace the water in the cells, bulking them up and preserving the shape of the wood. It is the same process that saved the Vasa and the Mary Rose.

But the team at Brede is also experimenting with new freeze-drying techniques for the smaller artifacts, and digital scanning for the hull. Every single plank, every rivet, every frame is being 3D scanned to sub-millimeter accuracy. Before the physical ship is even reassembled, a "Digital Colossus" will sail again in the virtual world, allowing researchers to simulate its hydrodynamics, stability, and speed.

Part VIII: The Legacy of the Leviathan

The discovery of the Copenhagen Colossus has come at a fascinating time for Denmark. The Lynetteholm project, which birthed the discovery, is itself a project of colossal scale, a modern echo of the ambition that built the ship. There is a poetic symmetry in the fact that the construction of a new island for the future has unearthed a giant from the past.

Plans are already underway for a new Maritime Museum wing to house the vessel. Unlike the Vasa museum, which is a dark, cathedral-like space, the proposed design for the Colossus exhibit is light and airy, located on the waterfront of the new Lynetteholm district, overlooking the very waters where the ship sank.

Rewriting HistoryAcademically, the Colossus is a disruptor. It forces us to rethink the scale of the medieval economy. It proves that the "Industrial Revolution" of logistics happened centuries earlier than we thought. The sheer capital investment required to build such a ship in 1410 would have been astronomical—equivalent to building a nuclear power plant today. It speaks of a society that was highly organized, financially sophisticated, and willing to take massive risks for massive rewards.

It also highlights the centrality of the Øresund in European history. This strait was the Suez Canal of the Middle Ages. He who controlled the Sound, controlled the wealth of Northern Europe. The Colossus was a tool of that control, a physical manifestation of the power struggle between the Danish Crown and the Hanseatic League.

The Human ConnectionBut beyond the economics and the engineering, the Colossus connects us to the people of the past. When you look at the worn heel of that leather shoe, or the soot stains on the bricks of the galley hearth, the 600 years melt away. You can smell the woodsmoke, feel the bite of the salt spray, and hear the creak of the massive timbers as the great ship ploughs through the grey Baltic waves.

We often think of the people of the Middle Ages as distant, superstitious, and primitive. The Copenhagen Colossus proves them to be engineers of genius, merchants of ambition, and sailors of immense courage. They built a leviathan to conquer the sea, and though the sea eventually claimed it back, they have, in the end, won the battle against oblivion.

As the conservation tanks at Brede hum with the work of preservation, the Copenhagen Colossus is slowly waking from its long slumber. It will no longer sail the oceans, but it will travel through time, carrying the story of a lost world into the future. The raising of the medieval leviathan is complete; the voyage of discovery has just begun.

Epilogue: The View from 2026

Standing on the construction site of Lynetteholm today, with the wind whipping off the Sound, it is hard to imagine the silence that reigned here for six centuries. The cranes of the modern port dominate the skyline, lifting containers that the captain of the Colossus could scarcely comprehend. But the spirit is the same. The drive to trade, to build, to push outward into the water is a continuous line from 1410 to 2026.

The Svælget 2—our Copenhagen Colossus—serves as a reminder that we stand on the shoulders of giants. We are not the first to build great things in these waters, and we will likely not be the last. But for now, we can marvel at the return of the King of the Cogs, a wooden wonder that has finally come home.

(End of Article)Author's Note on Sources and Context: This article is based on the archaeological findings reported regarding the shipwreck "Svælget 2" discovered off Copenhagen in late 2025/early 2026. Details regarding the ship's dimensions (approx. 28m x 9m), dating (c. 1410), and construction (Polish planking, Dutch frames, brick galley) are drawn from reports by the Viking Ship Museum and the excavation team led by Otto Uldum. The narrative of the "raising" describes the recovery conservation process typical for finds of this magnitude in the Baltic region.

Reference:

- https://www.vasamuseet.se/en

- https://news.artnet.com/art-world/largest-cog-shipwreck-svaelget-2-denmark-2735069

- https://www.express.co.uk/news/history/2152528/medieval-ship-found-world-largest-cog-archaeology

- https://news.artnet.com/art-world/largest-cog-shipwreck-svaelget-2-denmark-2735069?amp=1

- https://www.thearchaeologist.org/blog/massive-medieval-cog-ship-discovered-off-denmark-the-emma-maersk-of-the-middle-ages

- https://nauticalvoice.com/historic-discovery-largest-medieval-cargo-ship-found/80575/

- https://www.crafoord.se/utvaldabidrag/gribshunden-shipwreck-a-short-report-from-the-2019-excavation/

- https://arkeonews.net/massive-medieval-cog-ship-discovered-off-denmark-the-emma-maersk-of-the-middle-ages/

- https://nauticalvoice.com/historic-discovery-of-largest-medieval-cargo-ship-off-copenhagen/80882/

- https://archaeologymag.com/2026/01/world-s-largest-late-medieval-cog-ship/

- https://divemagazine.com/scuba-diving-news/worlds-largest-medieval-cog-discovered-off-copenhagen

- https://www.lunduniversity.lu.se/article/cutting-edge-science-reveals-gribshundens-shipwrecked-secrets

- https://maritime-executive.com/article/danish-archaeologists-uncover-largest-medieval-sailing-cog-ever-found