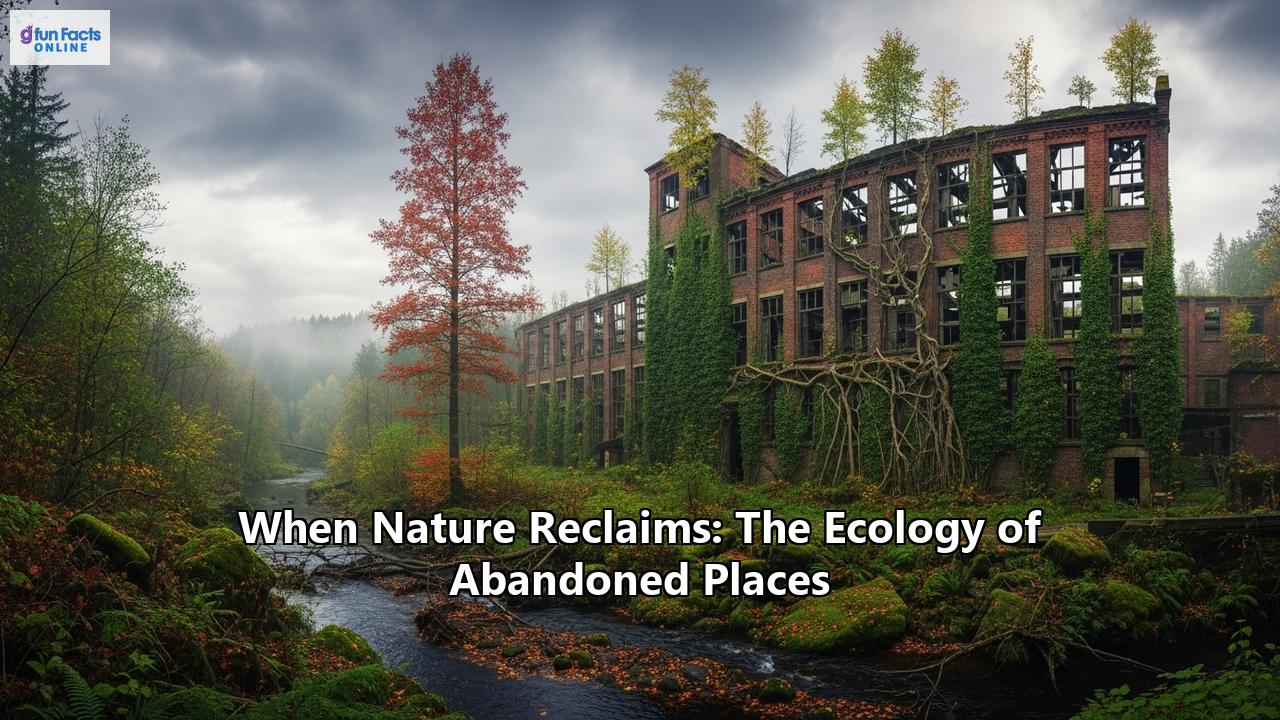

In a world relentlessly shaped by human hands, where concrete and steel have long dictated the landscape, there exists a quiet but powerful rebellion. It is a rebellion not of mankind, but of nature itself. When we abandon our creations, when the clamor of industry and the bustle of daily life cease, a subtle yet inexorable process begins. This is the story of nature’s reclamation, an intricate and often beautiful display of ecological resilience in the face of our forgotten worlds. From the radioactive wilderness of Chernobyl to the fortified ghost towns of Cyprus, the Earth is constantly demonstrating its ability to heal, adapt, and ultimately, to reclaim what was once its own. These abandoned places, monuments to human endeavor and sometimes to human folly, become accidental laboratories of evolution, offering profound insights into the tenacity of life and the intricate dance between man and nature.

The Unseen Architects of Renewal: The Process of Ecological Succession

The reclamation of abandoned places is not a chaotic free-for-all but a structured, often predictable process known as ecological succession. It is the orderly sequence of changes in an ecological community over time, a journey from barrenness to a complex, thriving ecosystem. In the context of our abandoned man-made world, this process takes on a unique character, a testament to life's ability to conquer even the most inhospitable of environments.

Primary and Secondary Succession: A Tale of Two Beginnings

Ecological succession is broadly categorized into two main types: primary and secondary. Primary succession occurs on landscapes devoid of life, where no soil or organic matter exists. Think of a newly formed volcanic island or a bare rock face exposed by a retreating glacier. In the urban context, a freshly paved parking lot or a new concrete structure represents a similar blank slate for nature to write upon.

Secondary succession, on the other hand, happens in areas where a previously existing ecosystem has been disturbed or removed, but the soil and some life remain. A forest after a fire, or a field left fallow, are classic examples. Abandoned cities, with their parks, gardens, and remnants of soil, largely undergo secondary succession, which is a much faster process than its primary counterpart.

The Pioneers: Life's Vanguard in the Concrete Jungle

The first organisms to colonize these desolate landscapes are the pioneer species. These are hardy, resilient organisms, the vanguard of nature's reclamation army. In the harsh, nutrient-poor environments of abandoned urban spaces, lichens and mosses are often the first to arrive. These incredible organisms are a symbiotic partnership between a fungus and an alga or cyanobacterium. They can cling to the most unforgiving surfaces – bare rock, glass, and even rusting steel.

Their colonization is not merely a matter of survival; it is an act of creation. Lichens produce weak acids that slowly, imperceptibly, begin to break down the surfaces they inhabit. Over time, these acids, combined with the accumulation of dust and the decomposition of the lichens themselves, create the very first layer of soil. This is a monumental step in the process of succession, the creation of a foothold for other, more complex life forms.

Following the lichens and mosses come the "weeds" – the hardy, fast-growing plants that are often scorned in our manicured gardens but are heroes in the story of reclamation. Species like dandelions, with their wind-dispersed seeds, and resilient grasses can take root in the thinnest of soils, their roots further breaking up the concrete and asphalt. Their life and death cycles continue to enrich the nascent soil, paving the way for larger and more demanding plants.

From Cracks to Canopies: The Green Conquest

As the soil deepens and becomes more fertile, the process of succession accelerates. Shrubs and small trees, like buddleia (the "butterfly bush"), often a common sight in urban wastelands, begin to appear. Their seeds, often dispersed by birds or the wind, find purchase in the growing pockets of soil in cracks and crevices of buildings. As these larger plants grow, their roots exert immense pressure, widening cracks, crumbling concrete, and toppling walls. This constant, slow-motion demolition is a key part of nature's reclamation toolkit.

Over decades, if left undisturbed, these pioneer communities are gradually replaced by more competitive, longer-lived species. In many temperate regions, abandoned urban areas will eventually see the rise of forests. The specific types of trees that come to dominate will depend on the climate, the soil conditions, and the seeds that are available in the surrounding landscape. The end point of this process is the climax community, a relatively stable ecosystem that can persist for long periods. However, in the dynamic environment of an abandoned city, this "climax" may be a constantly shifting mosaic of different habitats.

The Ghosts in the Machine: How Man-Made Structures Shape the New Wilderness

The presence of our abandoned structures adds a fascinating layer of complexity to the process of ecological succession. Buildings create a variety of microclimates. The shaded, cooler north-facing walls of a skyscraper will support different plant life than the sun-baked, south-facing walls. The "urban canyons" created by tall buildings can channel wind, creating wind tunnels in some areas and sheltered pockets in others. These variations in light, temperature, and wind create a patchwork of different habitats within a small area, contributing to a surprising level of biodiversity.

The materials we used to build our world also play a crucial role. Concrete, with its high pH, presents a challenging environment for many plants. However, the gradual leaching of calcium from the concrete can actually benefit some species. Steel, on the other hand, rusts and corrodes, releasing iron into the soil, which can be a vital nutrient for some plants. A 2020 study comparing the environmental impacts of steel and concrete construction found that concrete has a higher overall pollution potential, and at the end of its life, concrete rubble is often destined for landfills, while steel can be recycled. This difference in material fate also influences the long-term ecological trajectory of an abandoned site.

Contamination is another significant factor, particularly in abandoned industrial areas. Soil can be laced with heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and other toxic substances, a legacy of our industrial past. This contamination can slow down or alter the course of succession, favoring the growth of specialized, tolerant plant species. In some cases, certain plants can even help to clean up the soil through a process called phytoremediation. However, in highly contaminated sites, the ecological recovery can be severely stunted, leaving a scarred landscape that may take centuries, or even millennia, to fully heal.

Whispers of the Wild: Case Studies in Ecological Reclamation

The story of nature's reclamation is not just a scientific process; it is a collection of captivating tales from around the globe. Each abandoned place has its own unique story of decline and rebirth, a testament to the enduring power of the natural world.

Chernobyl's Exclusion Zone: A Radioactive Eden

Perhaps no place on Earth better exemplifies the astonishing resilience of nature than the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Following the catastrophic nuclear accident in 1986, a 1,000-square-mile area around the plant was evacuated, leaving behind a ghost city, Pripyat, and a landscape saturated with radiation. The immediate aftermath was devastating. A nearby pine forest turned a ghastly reddish-brown and died, earning it the name the "Red Forest".

But in the decades since, in the absence of humans, the Exclusion Zone has transformed into a stunning, albeit radioactive, wilderness. It has become a haven for a remarkable array of wildlife. Wolves, whose populations are now seven times denser than in surrounding reserves, roam the empty streets of Pripyat. Herds of wild boar and roe deer graze in the overgrown fields. Rare and endangered species, such as the European bison and the elusive Eurasian lynx, have made a comeback. Even the Przewalski's horse, a rare and endangered species of wild horse, has found a sanctuary here, with a population of around 150 individuals now thriving in the zone.

The plant life has also staged a remarkable recovery. The "Red Forest" is slowly being replaced by deciduous trees like birch and aspen, which are more resistant to radiation. In Pripyat, the once-manicured lawns and parks are now dense forests. A study of the city's trees found 20 different species, with a high density of regenerating seedlings, suggesting a healthy and evolving urban forest. However, the legacy of the disaster is not entirely gone. Some studies have shown that insects and spiders have lower populations in more radioactive areas, and some animals, like voles, show higher rates of cataracts and reduced fertility. Yet, the overwhelming story of Chernobyl is one of unexpected and vibrant life, a powerful testament to the fact that the absence of humans can be a more powerful force for ecological recovery than even the presence of deadly radiation.

The Korean Demilitarized Zone: An Accidental Paradise

Stretching 155 miles across the Korean Peninsula, the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) is one of the most heavily fortified borders in the world. A 2.5-mile-wide ribbon of land, it has been largely untouched by humans since the end of the Korean War in 1953. This "accidental paradise" has become a vital refuge for wildlife on the Korean Peninsula, a place where nature has been allowed to flourish in the absence of human activity.

The DMZ is home to an astonishing array of biodiversity. Over 5,000 species of plants and animals have been identified within its borders, including 101 endangered species. The diverse landscape, which includes mountains, forests, wetlands, and prairies, provides a habitat for a wide range of creatures. The wetlands of the western DMZ are a crucial wintering ground for the red-crowned and white-naped cranes, two of the world's most endangered crane species. In the mountainous eastern regions, the rare Amur goral, a type of wild goat, and the Siberian musk deer find sanctuary. There are even tantalizing camera-trap images of the elusive Asiatic black bear, suggesting a breeding population may exist within the zone.

The rewilding of the DMZ has been a process of secondary succession. Former rice paddies and agricultural lands have transformed into lush wetlands and forests. The lack of human interference has allowed these ecosystems to mature and develop a complexity that is rarely seen elsewhere on the heavily populated Korean Peninsula. The DMZ stands as a poignant symbol of how nature can heal the wounds of war, creating a vibrant and biodiverse landscape in the very place where human conflict reached its zenith.

Hashima Island, Japan: A Concrete Battleship Reclaimed by Green

Off the coast of Nagasaki lies a small, fortified island that resembles a battleship from a distance, earning it the nickname Gunkanjima, or "Battleship Island." This is Hashima Island, a former coal mining facility that was once the most densely populated place on Earth. In 1959, over 5,000 people lived on this tiny 16-acre island, packed into a maze of concrete apartment blocks, schools, and hospitals. But when the coal ran out in 1974, the island was abandoned almost overnight, left to the mercy of the wind and waves.

Today, Hashima is a ghost island, a haunting monument to Japan's rapid industrialization and its subsequent decline. The concrete buildings are crumbling, their interiors exposed to the elements. But amidst the decay, nature is staging a quiet takeover. Hardy plants, their seeds carried by the wind and birds, have taken root in the cracks and crevices of the concrete jungle. Ferns, mosses, and grasses have colonized the open spaces and rooftops, creating a surreal landscape of green against a backdrop of gray, decaying concrete.

The reclamation of Hashima is a powerful example of primary succession on a man-made landscape. The island's harsh environment, with its salty sea spray and lack of soil, presents a significant challenge to plant life. Yet, life has found a way. The pioneer plants are slowly breaking down the concrete, creating a more hospitable environment for other species to follow. Hashima is a living laboratory for studying how life can colonize even the most sterile of environments, a slow-motion testament to the relentless advance of the natural world.

Varosha, Cyprus: A Ghost Resort Returning to the Wild

In the 1970s, Varosha was the premier tourist destination in Cyprus, a glittering strip of high-rise hotels and pristine beaches that attracted celebrities like Elizabeth Taylor and Brigitte Bardot. But in 1974, following the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the city was fenced off and abandoned, becoming a ghost town in the UN-patrolled buffer zone.

For nearly 50 years, Varosha has been frozen in time, a surreal landscape of decaying hotels and empty streets. But while the man-made world has crumbled, nature has been quietly at work. Prickly pear bushes have overrun the once-manicured gardens, and trees have sprouted through the floors of abandoned apartments. The streets have cracked under the relentless sun, and wildflowers have pushed their way through the pavement.

The buffer zone in which Varosha is located has become a de facto wildlife sanctuary. It is home to the endangered Cyprus mouflon, a type of wild sheep, as well as rare orchids and the Cyprus spiny mouse. Sea turtles, once a rare sight, now nest on the deserted beaches of Varosha, their eggs safe from human disturbance. The story of Varosha is a poignant reminder that even in the midst of political conflict and human division, nature can find a way to create a space of its own, a wild and beautiful kingdom in the heart of a ghost city.

Kennecott, Alaska: A Copper Kingdom in the Wilderness

Nestled deep within the vast wilderness of Alaska's Wrangell-St. Elias National Park lies the ghost town of Kennecott. In the early 20th century, this was a bustling copper mining camp, home to a state-of-the-art mill and a community of several hundred workers. But when the high-grade copper ore was depleted in 1938, the mines were abandoned, and the town was left to the elements.

Today, the striking red mill building and other historic structures of Kennecott stand as a National Historic Landmark, a testament to the ambition and ingenuity of the early miners. But surrounding these man-made relics is a landscape that is slowly being reclaimed by the Alaskan wilderness. The natural succession of plant life is a key feature of the area, with the National Park Service managing vegetation to preserve the historic buildings. Mountain goats, Dall sheep, and bears can be spotted in the rugged mountains that surround the town, and the nearby Root Glacier provides a stunning backdrop to this scene of industrial decay and natural renewal. Kennecott is a powerful example of how even the most remote and ambitious of human endeavors can eventually be dwarfed by the immense power of the natural world.

The Salton Sea, California: A Toxic Oasis and Its Hardy Survivors

The Salton Sea, California's largest lake, is a man-made accident, born in 1905 when the Colorado River breached an irrigation canal and flooded a desert basin. For a time, it was a glamorous resort destination, a "miracle in the desert" that attracted celebrities and tourists alike. But as agricultural runoff poured into the lake, its salinity soared, and its waters became a toxic soup of pesticides and fertilizers.

Today, the Salton Sea is a shadow of its former self, a place of abandoned resorts and dying fish. And yet, even in this seemingly desolate landscape, life clings on. The sea has become a crucial stopover for migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway, with over 400 species recorded in the area. The desert pupfish, a native species, has adapted to the extreme salinity and pollution, a testament to the incredible adaptability of life. And in the hyper-saline waters, extremophile bacteria thrive, creating a unique and little-understood ecosystem. The ruins of the abandoned resorts and the stark beauty of the dying sea create a surreal and strangely beautiful landscape, a powerful reminder of the unintended consequences of our actions and the incredible tenacity of life in the most extreme of environments.

Pavlopetri, Greece: An Ancient City Becomes a Modern Reef

Submerged beneath the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean, off the coast of southern Greece, lies the ancient city of Pavlopetri. At over 5,000 years old, it is the oldest known submerged city in the world, a Bronze Age metropolis of streets, buildings, and tombs that was swallowed by the sea around 1100 B.C.

Today, Pavlopetri is a unique underwater archaeological site, a window into a long-lost world. But it is also a thriving marine ecosystem. The ancient stones of the city have become an artificial reef, providing a habitat for a diverse array of marine life. Fish dart through the doorways of submerged houses, and colorful seaweeds and sponges cling to the ancient walls. The story of Pavlopetri is a fascinating example of how even our most ancient and forgotten creations can be repurposed by nature, becoming a vibrant and living part of the marine landscape.

Novel Ecosystems: A New Way of Seeing Nature's Handiwork

As nature reclaims our abandoned creations, it doesn't always recreate the ecosystems that were there before. Often, what emerges is something entirely new, a "novel ecosystem" composed of a mixture of native and non-native species living in a human-altered environment. These novel ecosystems are becoming increasingly common in our rapidly changing world, and they present a significant challenge to traditional ideas of conservation and restoration.

The concept of novel ecosystems sparks a lively debate among ecologists and conservationists. Some argue that these new ecosystems are a pragmatic reality, and that we should focus on managing them to maximize the benefits they provide, such as filtering water, storing carbon, and providing habitat for wildlife. Others are more cautious, warning that accepting novel ecosystems could lead to a "get out of jail free" card for polluters and developers, and could distract from the crucial work of protecting and restoring our planet's remaining pristine wilderness.

The abandoned landscapes we have explored in this article are prime examples of novel ecosystems. The radioactive wilderness of Chernobyl, with its mix of native wildlife and introduced species like the Przewalski's horse, is a classic example. The urban forests of Pripyat, with their unique blend of ornamental and native trees, are another. These places challenge us to think beyond our traditional ideas of what is "natural" and to develop new, more flexible approaches to conservation in a world that has been profoundly and irrevocably shaped by human hands.

The Human Element: Living with the Ghosts of Our Past

The reclamation of abandoned places is not just an ecological story; it is also a human one. These landscapes are imbued with memory and meaning, reminders of our past ambitions, our failures, and our complex relationship with the natural world. They can be places of great beauty and scientific wonder, but also of danger and sadness.

The abandoned industrial sites of our past can pose significant risks to human health and the environment. The legacy of contamination can persist for centuries, a toxic ghost that haunts the landscape. But these places can also offer unexpected benefits. They can become havens for biodiversity, providing a refuge for species that are struggling to survive in our increasingly developed world. They can serve as living laboratories for scientists, offering invaluable insights into the processes of ecological succession and the resilience of life. And they can be powerful places of reflection, reminding us of the fragility of our creations and the enduring power of the natural world.

A Green and Silent Requiem: The Future of Our Abandoned Worlds

As we look to the future, the number of abandoned places is likely to grow. Climate change, economic shifts, and changing demographics will continue to reshape our world, leaving behind a new generation of ghost towns, abandoned factories, and forgotten landscapes. But as we have seen, this is not just a story of loss and decay. It is also a story of hope and renewal.

The reclamation of our abandoned worlds is a powerful testament to the resilience of life. It is a reminder that even in the face of our most destructive actions, nature has an incredible capacity to heal, to adapt, and to create something new and beautiful. These landscapes are not just graveyards of our past; they are also cradles of a new and wilder future. They are a silent requiem for what has been lost, but also a vibrant and hopeful chorus for what is yet to come. They teach us that in the end, nature always finds a way, and that even in our absence, the world will continue to be a place of breathtaking beauty and wonder.

Reference:

- https://birdsbloomsandbumbles.com/the-concrete-jungle-plants-of-waste-ground-and-wayside/

- https://www.ck12.org/flexi/life-science/succession/after-a-town-is-abandoned-the-concrete-parking-lots-remain-empty-and-inactive-for-hundreds-of-years-order-the-plants-by-ecological-succession-from-the-first-to-occur-to-the-last-to-occur-shrubs-trees-lichens-grass/

- https://www.google.com/search?q=time+in+JP

- https://www.wmf.org/monuments/pavlopetri

- https://sigmaearth.com/the-ecology-of-abandoned-urban-spaces/

- https://www.quora.com/Why-do-weeds-and-plants-grow-in-abandoned-buildings-but-not-in-normal-ones

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salton_Sea

- https://www.cornell.edu/video/wild-urban-plants

- https://saltonseaforum.ucr.edu/environment-salton-sea

- https://www.uvm.edu/~jfarley/UFSC/grupos%20de%20trabalho/indices/indices%20lit/Management_of_novel_ecosystems%5B1%5D.pdf

- https://app.advcollective.com/alaska/Hiking/historic-mining-ruins-and-scenic-wilderness-at-kennecott-mines,-alaska

- https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/pavlopetri/

- https://ensia.com/voices/novel-ecosystems-are-a-trojan-horse-for-conservation/

- http://www.pavlopetri.org/p/the-story-of-pavlopetri.html

- https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/novel-ecosystems-implications-for-conservation-and-restoration

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/conservation-strategies-novel-ecosystems

- https://eco.confex.com/eco/2016/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/57940

- https://www.ces.fau.edu/usgs/pdfs/session-a-resource-2.pdf

- https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/files/1573482/%E2%80%8C11401_%E2%80%8CPID11401.pdf

- https://www.google.com/search?q=time+in+Copper+River+Census+Area,+US

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265736751_The_Pavlopetri_Underwater_Archaeology_Project_investigating_an_ancient_submerged_town

- https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/oldest-submerged-city-5000-old-sunken-perfectly-designed-city-south-greek

- https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/17/10829

- https://www.quora.com/How-can-plants-grow-out-of-concrete-or-abandoned-buildings

- https://www.nemuno7.lt/en/plants-pioneers/

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/1631109.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358433567_Urban_post-industrial_landscapes_have_unrealized_ecological_potential

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pioneer_species

- https://travelshelper.com/magazine/unusual-places/varosha-from-popular-and-modern-tourist-hotspot-to-the-ghost-town/

- https://saltonseaforum.ucr.edu/sites/default/files/2024-06/the-ecology-of-the-salton-sea-basin_allen2024_0.pdf

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/salton-sea-history

- https://www.california.com/what-happened-salton-sea/

- https://www.themodernpostcard.com/the-salton-sea-a-ghost-of-former-glory-in-the-california-desert/

- https://www.witpress.com/Secure/elibrary/papers/SC19/SC19030FU1.pdf