The abyss does not forgive, and it does not forget. But mostly, it waits.

For centuries, humanity looked upon the ocean’s surface and imagined monsters—krakens, leviathans, serpents of the deep. We projected our fears of teeth and claws onto the darkness. But nature, in its infinite and terrifying creativity, had a different design in mind. It didn't need teeth. It didn't need eyes. It didn't even need a brain. It simply needed to wait.

In the crushing blackness of the Antarctic deep sea, where the pressure can turn a steel submarine into scrap metal and the water temperature hovers just above freezing, a new horror has been found. It is not a shark, nor a squid. It is a sponge.

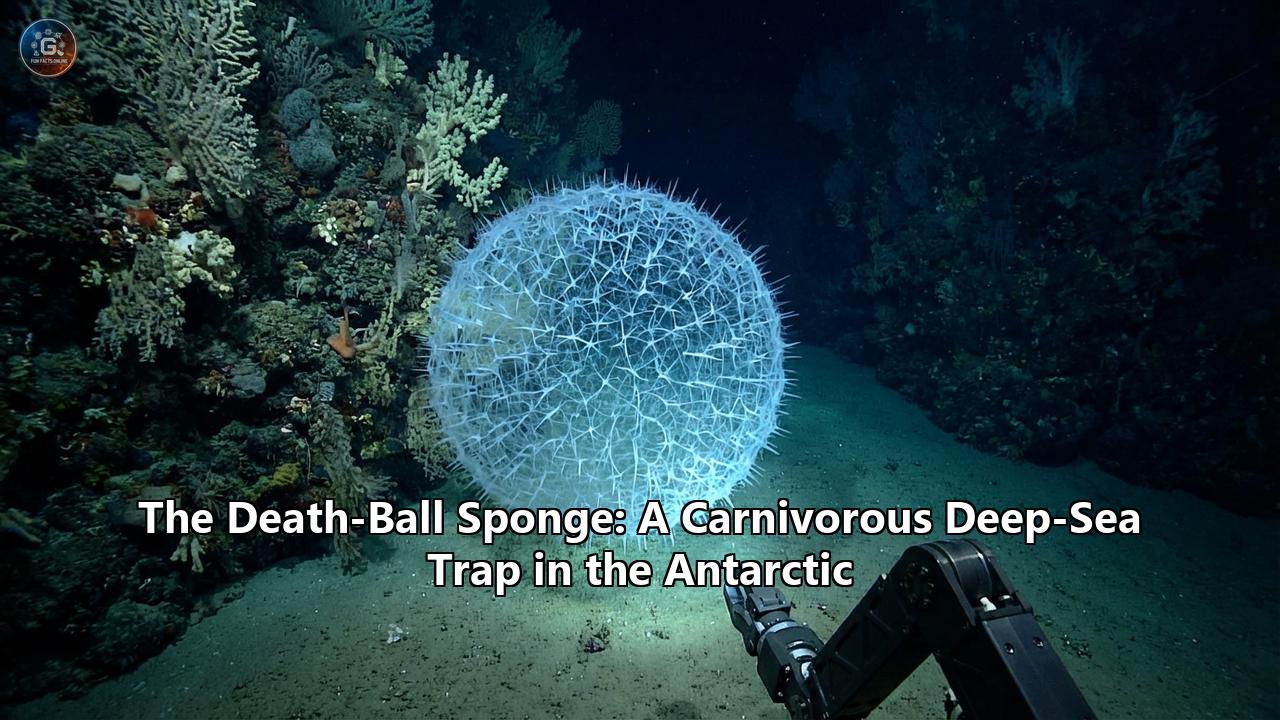

But this is not the loofah sitting in your shower. This is the Death-Ball Sponge (Chondrocladia sp. nov.), a newly discovered carnivorous predator that has subverted 600 million years of evolutionary biology to become one of the most efficient, silent, and terrifying traps on the planet.

Discovered in late 2025 by the Nippon Foundation-Nekton Ocean Census expedition, this organism has captivated and unsettled the scientific community. It is a creature that looks like a forgotten toy left in the dark—a stalked, alien structure adorned with spherical, cloud-like orbs. But those orbs are not for decoration. They are lethal snares, covered in microscopic hooks that snag passing crustaceans, holding them fast while the sponge’s cells slowly migrate to the surface to digest the prey alive.

This is the story of the Death-Ball Sponge, the expedition that found it, and the frozen, alien world it calls home.

Part I: The Edge of the Map

To understand the Death-Ball, one must first understand the arena in which it survives. The Southern Ocean, encircling Antarctica, is the wildest, most isolated body of water on Earth. It is protected by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, a vortex of water that effectively seals off the continent from the rest of the world, creating a unique evolutionary incubator.

Here, the water is rich in oxygen but paradoxically poor in food—at least, the kind of food most sponges eat. In the sunlit surface waters, phytoplankton bloom in massive numbers during the summer, but as you descend, that life fades. By the time you reach the bathyal and abyssal zones—1,000 to 4,000 meters down—the "marine snow" (falling organic debris) has been picked over by a thousand other mouths.

It was into this hostile void that the research vessel Falkor (too), operated by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, sailed in late 2025. The mission was part of the Ocean Census, a global alliance dedicated to discovering 100,000 new marine species in a decade. The target: the South Sandwich Trench, a subduction zone where the South American plate grinds beneath the South Sandwich plate, creating a landscape of deep trenches and volcanic seamounts.

The team, led by biological oceanographers from the University of Essex and other institutions, deployed the ROV SuBastian, a remote-operated vehicle capable of withstanding the immense pressures of the deep. As the ROV descended, the light from the surface vanished. The cameras switched to artificial floodlights, carving a tunnel of visibility through the eternal night.

At 3,601 meters (11,814 feet)—a depth where the pressure is roughly equivalent to an elephant standing on your thumb—the pilots spotted something strange east of Montagu Island.

It wasn't a rock. It wasn't a piece of drift plastic. It stood upright, anchored to the sediment by a root-like holdfast. A stalk rose from the mud, branching out into a candelabra of terrifying elegance. At the tip of each branch sat a pale, translucent sphere. It looked like a spectral tree bearing forbidden fruit.

"It looks like a death star," one researcher reportedly murmured. The nickname stuck. The Death-Ball Sponge had been found.

Part II: Anatomy of a Silent Killer

The Death-Ball Sponge belongs to the family Cladorhizidae, a group of deep-sea sponges that have abandoned the filter-feeding lifestyle of their shallow-water cousins.

To understand how radical this is, consider what a sponge usually is. A typical sponge is a living pump. It draws water in through thousands of tiny pores (ostia), filters out bacteria and organic particles using specialized collar cells (choanocytes), and ejects the clean water through a larger hole (osculum). It is a pacifist existence, relying on the gentle drift of currents.

The Death-Ball Sponge has dismantled this machinery. It has no choanocytes. It has no water canals. It has no need for flow. In the stagnant silence of the trench, pumping water costs too much energy for too little reward. Instead, it has evolved to become a meat-eater.

The Stalk and BranchesThe body of Chondrocladia sp. nov. is structured for maximum coverage. A central peduncle lifts the feeding structures off the muddy seafloor, placing them in the path of drifting currents where small crustaceans might be swimming or tumbling. From this stalk, multiple branches radiate outward, creating a 3D trap.

The "Death Balls"The defining features are the spheres at the tips of the branches. These are not solid balls of tissue; they are inflatable, fluid-filled balloons supported by a delicate lattice of silica spicules (the sponge's skeleton). This structure maximizes surface area while minimizing metabolic cost. The sponge doesn't need to maintain a solid block of flesh; it just needs a net.

The Velcro of DoomIf you were to look at the surface of these spheres under a scanning electron microscope, the "smooth" appearance would vanish. Instead, you would see a forest of nightmares. The surface is densely coated with specialized spicules called chelæ.

Imagine a microscopic grappling hook. Now imagine millions of them, shaped like anchors, hooks, and serrated knives, all interlocking and facing outward. This is the sponge's skin. It acts exactly like Velcro. When a small crustacean—like an amphipod or an isopod—brushes against one of the spheres, its hairy legs or antennae get snagged on the spicules.

The more the prey struggles, the more entangled it becomes. It is the same principle as a fly caught in a spider's web, but purely mechanical. There is no sticky silk, just thousands of glass hooks refusing to let go.

Part III: The Digestion

The horror of the Death-Ball Sponge lies not in the capture, but in the consumption.

Unlike a Venus flytrap, which snaps shut, the sponge has no muscles. It cannot move quickly. The capture is instantaneous, but the eating is agonizingly slow.

Once the prey is trapped, chemical sensors on the sponge's surface detect the struggle and the presence of foreign proteins. This triggers a response that is almost unheard of in the animal kingdom. The sponge's cells—specifically amoebocytes, which are mobile cells capable of changing shape—begin to migrate toward the trapped victim.

Slowly, over the course of hours, the sponge's flesh begins to flow over the prey. It surrounds the struggling crustacean, encasing it in a living tomb of cytoplasm. There is no mouth to swallow the food, no stomach to digest it. The sponge digests the prey cellularly.

Individual cells release digestive enzymes directly onto the crustacean, breaking down its exoskeleton and dissolving its soft tissues into a nutrient soup. The sponge then absorbs this soup directly through its cell membranes. It is arguably one of the most gruesome ways to die in the ocean: to be held fast by glass hooks while the wall you are pinned against slowly melts you down and drinks you.

When the digestion is complete, the sponge cells retreat, leaving behind only the clean, empty husk of the crustacean's exoskeleton, which eventually falls away, resetting the trap for the next victim.

Part IV: The Evolutionary Paradox

Why did a sponge, the simplest of multicellular animals, turn to violence?

The answer lies in the economics of the abyss. The deep sea is an "oligotrophic" environment—nutrient-poor. The particle-rich water of the surface doesn't reach these depths in sufficient quantities to support a filter feeder. A traditional sponge would starve to death trying to pump enough water to find a few calories of bacteria.

However, the deep sea does have a relatively high population of small crustaceans. Amphipods, isopods, and copepods thrive here, scavenging on falls of carrion. For a stationary organism, these crustaceans represent massive, concentrated packets of energy—the difference between finding a crumb of bread (bacteria) and finding a steak dinner (a shrimp).

Evolution is a pragmatist. Over millions of years, the ancestors of the Cladorhizidae lost their water-pumping system. Their Choanocytes—the cells that define sponges—were discarded. In their place, the spicules, originally used for structural support and defense, were repurposed into weapons.

This transition is so radical that when carnivorous sponges were first discovered in the Mediterranean caves in 1995 (the species Asbestopluma hypogea), scientists initially didn't believe they were sponges at all. They looked more like hydroids or strange algae. It wasn't until genetic testing and close observation confirmed their lineage that the scientific world accepted that the gentle sponge had a killer cousin.

The Death-Ball Sponge represents the pinnacle of this adaptation. Its spherical shape offers the perfect surface-area-to-volume ratio for trapping prey coming from any direction in the 3D void of the water column.

Part V: Neighbors in the Dark

The Death-Ball Sponge was not the only discovery made by the Ocean Census team. It was merely the headliner of a grotesque and beautiful circus of life found in the South Sandwich Trench.

*The Zombie Worms (Osedax)

Found nearby on the bones of a dead whale, the team identified new variants of Osedax, the so-called "zombie worms." These creatures have no mouth, no stomach, and no anus. They survive by drilling "roots" into the bones of fallen leviathans. Inside these roots, symbiotic bacteria digest the fats and oils trapped in the bone marrow, feeding the worm. The males of the species are microscopic dwarfs that live inside the female's tube, existing solely to fertilize eggs—a life cycle as bizarre as the sponge’s.

The Iridescent Scale WormGlittering like a disco ball in the ROV's lights, a new species of scale worm (Polynoidae) was found. Covered in armored plates that diffract light, this predator scuttles across the sediment. Why be iridescent in a world without light? It remains a mystery. Some theorize it may be a form of mimicry or a byproduct of the shell's structure, visible only when intruders bring their own light.

The SeastarsThree new species of seastars were identified, some with arms so long and slender they looked like crinoids. These creatures act as the cleanup crew of the trench, moving slowly over the sediment to consume whatever organic detritus has fallen from above.

Together, these animals form a complex food web in a place where photosynthesis is impossible. They rely on "chemosynthesis" (energy from chemical reactions at vents) or the "detrital rain" from the surface. The Death-Ball Sponge sits near the top of this localized food chain, a stationary apex predator of the micro-world.

Part VI: The Significance of the Find

The discovery of Chondrocladia sp. nov. is more than just a cool monster for science fiction writers to exploit. It has profound implications for our understanding of biodiversity and resilience.

1. The Undiscovered MajorityWe know more about the surface of Mars than we do about the bottom of our own oceans. The Ocean Census estimates that we have identified only about 10% of marine species. Finding a creature as large and complex as the Death-Ball Sponge highlights how much major macro-life is still hidden. If we can miss a "death ball" the size of a lamp, what else are we missing?

2. Adaptation LimitsThe Death-Ball Sponge shows us the extreme limits of life. It demonstrates that the definition of a phylum is flexible. Sponges were defined by filter feeding—until they weren't. This plasticity suggests that life on other planets (like the subsurface oceans of Europa or Enceladus) might defy our rigid biological categorizations.

3. The Fragility of the DeepThese creatures grow incredibly slowly. In the freezing, low-energy environment of the Antarctic, a sponge might take decades or even centuries to reach maturity. This makes them incredibly vulnerable. A single trawling net dragging along the bottom could wipe out a forest of Death-Ball Sponges that has stood for a millennium. The discovery reinforces the urgent need for Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the high seas.

Part VII: The Future of the Death-Ball

As of early 2026, the specimen collected by SuBastian is undergoing rigorous analysis. Taxonomists are examining its spicules to give it a formal Latin species name (though "Death-Ball" will likely stick in the public consciousness). Geneticists are sequencing its DNA to see where it fits in the tree of life, potentially unlocking secrets about the early evolution of animals.

But for every question answered, a dozen more arise.

- How does it reproduce? (Most sponges broadcast spawn, but in the vastness of the trench, finding a mate is hard. Does it bud? Is it hermaphroditic?)

- What eats the Death-Ball? (Is there a specialized sea slug or starfish that has evolved armor to bypass the hooks?)

- How long do they live? (Deep-sea glass sponges are known to live for thousands of years. The Death-Ball could be ancient.)

Epilogue: Waiting in the Dark

Imagine you are a small crustacean in the South Sandwich Trench. You have lived your entire life in absolute darkness, navigating by touch and chemical trails. You smell something—a faint drift of organic matter. You swim towards it, your antennae twitching.

You bump into something soft. A sphere. It feels harmless, yielding. You try to push off, but your leg is caught. You pull, but the grip tightens. You thrash, and another leg is snagged. The water is still. There is no sound. There is no predator breathing down your neck, no jaws snapping. Just a silent, white orb glowing faintly in the bioluminescence of the deep.

And then, slowly, the walls begin to close in.

The Death-Ball Sponge is a reminder that nature is not always a battle of strength and speed. Sometimes, the most effective weapon is patience. And in the deep, dark places of the world, patience is the only thing that matters.

Deep Dive: The Science of Spicules

To truly appreciate the engineering nightmare that is the Death-Ball Sponge, we must zoom in—way in. The "hooks" that make this sponge a killer are called spicules. In most sponges, spicules are structural elements made of silica (glass) or calcium carbonate. They act like the rebar in concrete, holding the sponge's shape against the current.

In the Cladorhizidae family, however, spicules have been weaponized. The specific type found on the Death-Ball is likely a variation of the anisochela. Imagine a C-shaped clip with teeth. Now imagine that these clips are arranged in rosettes or dense fields on the surface of the "ping-pong" balls.

When an exoskeleton—which is rough on a microscopic level—brushes these spicules, the hooks catch in the microscopic grooves of the shell. It is a mechanical lock. The force required to break the silica hook is often greater than the force the crustacean can generate.

Furthermore, some research into related carnivorous sponges suggests that the spicules might be coated in a slightly adhesive substance, or that the sponge tissue itself possesses a "stickiness" that aids the initial capture before the mechanical hooks take over.

The Cousins: The Harp and the Ping-Pong Tree

The Death-Ball Sponge is not alone in its family. It joins a gallery of grotesquely beautiful carnivorous sponges:

- The Ping-Pong Tree Sponge (Chondrocladia lampadiglobus): Perhaps the closest relative to the Death-Ball. Found in the Pacific, it looks like a candelabra with white spheres. It was the first "celebrity" carnivorous sponge.

- The Harp Sponge (Chondrocladia lyra): Discovered off the coast of California, this sponge looks like a lyre or a harp. It uses vertical vanes covered in hooks to trap prey, maximizing its surface area in current flow.

- The Killer Fan (Asbestopluma): These look like delicate feathers or fans, but they are just as deadly, stripping small prey of life with efficient ruthlessness.

The Death-Ball differs in its specific morphology—the "ball" shape is more pronounced and dense, likely an adaptation to the specific currents of the Antarctic trench, where eddies might bring food from multiple directions rather than a single prevailing current.

The Human Element: The Ocean Census

The discovery of the Death-Ball Sponge is a triumph for the Ocean Census*, arguably the most ambitious biological project of the 21st century. Launched by The Nippon Foundation and Nekton, its goal is to bridge the gap between the known and the unknown.

Why does it matter? Why spend millions of dollars to find a sponge that eats shrimp?

Because biodiversity is the library of the earth, and we are burning the books before we read them. Deep-sea organisms are sources of new medicines (antibiotics, anti-cancer drugs), new materials (fiber optics modeled after sponge spicules), and new understandings of carbon cycling.

The Death-Ball Sponge, living in the carbon-rich sediments of the Antarctic, plays a role in the global carbon cycle. By eating detritivores, it sequesters carbon in its body and eventually in the sediment. Disturbing these ecosystems could release millennia of stored carbon.

Conclusion

The Death-Ball Sponge is a monster, yes. But it is a marvelous one. It is a testament to life's refusal to quit. Put an animal in the dark, take away its food, crush it with pressure, and freeze it—and it will not only survive, it will turn into a glass-boned, meat-eating, death-star-shaped predator.

As we continue to explore the Southern Ocean, we will undoubtedly find more creatures that defy our expectations. But for now, the Death-Ball Sponge reigns supreme as the king of the Antarctic abyss—a silent, spherical trap waiting in the eternal night.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chondrocladia

- https://oceancensus.org/press-release-carnivorous-death-ball-sponge-among-30-new-deep-sea-species-from-the-southern-ocean/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pmS_JBbwLf4

- https://www.essex.ac.uk/news/2025/11/07/carnivorous-death-ball-sponge-discovered

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqWuKX07HLQ

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/oct/29/carnivorous-death-ball-sponge-among-new-species-found-in-depths-of-southern-ocean

- https://oceanographicmagazine.com/news/carnivorous-death-ball-sponge-among-new-deep-sea-species/

- https://blog.canpan.info/yoheisasakawa/archive/841

- https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/animals/a69234817/carnivorous-death-ball/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PH9fM_NYv2I

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/researchers-discover-death-ball-sponge-and-dozens-of-other-wacky-deep-sea-creatures-in-the-southern-ocean-180987609/