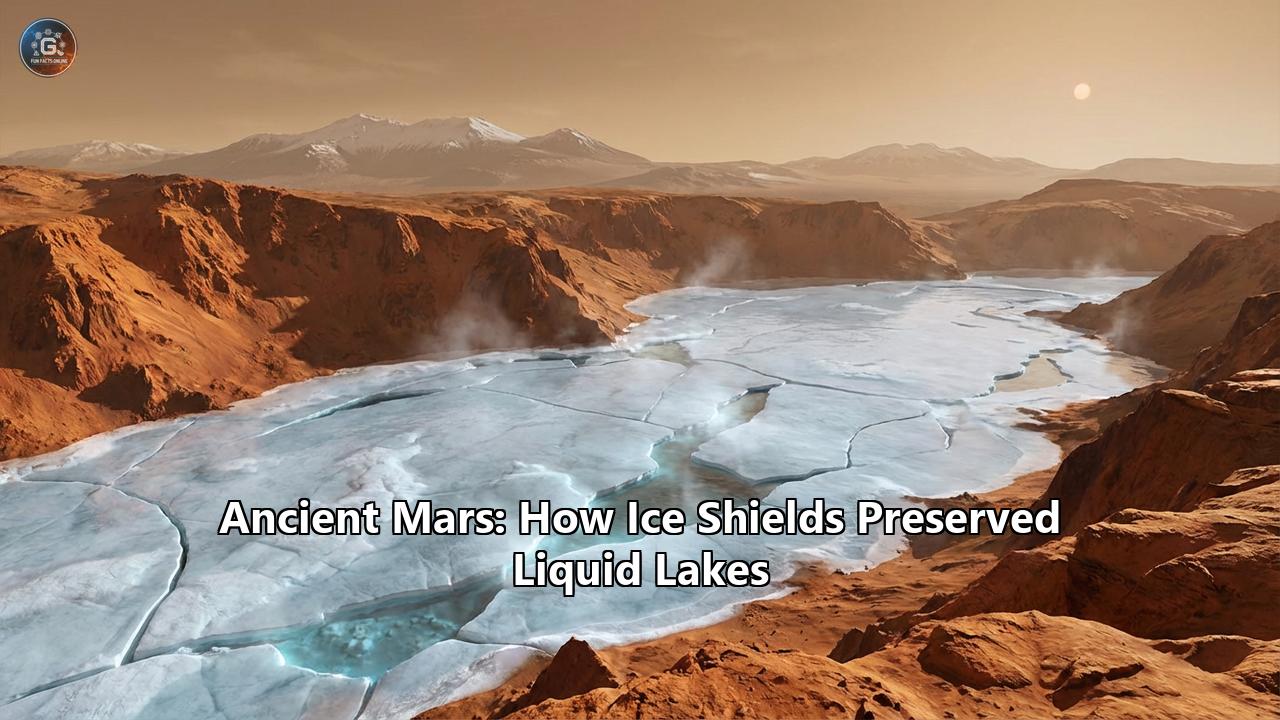

Standing on the rim of Gale Crater three and a half billion years ago, the view would have been alien, yet hauntingly familiar. The sky, a bruised peach color, hung heavy over a landscape that was not the rust-red desert of today, but a kaleidoscope of whites, greys, and piercing blues. Below, in the basin where NASA’s Curiosity rover now trundles over dry dust, lay a vast body of water. But this was not a tropical paradise. The air was frigid, biting enough to freeze exposed skin in seconds. Yet, the water remained liquid.

For decades, this scene has presented planetary scientists with a paradox that seemed impossible to resolve. We see the geological scars of flowing rivers, branching valleys, and sediment deltas that could only have been carved by liquid water. Yet, climate models insist that the ancient sun was too faint—shining with only 70% of its current brightness—to keep Mars warm enough for rain. Mars should have been a frozen wasteland, a "Snowball Mars."

Now, a groundbreaking new theory has emerged that bridges this divide, offering a solution as elegant as it is counterintuitive. The answer lies not in a thick, warming atmosphere, but in the ice itself. New research suggests that ancient Martian lakes were shielded by "seasonal ice lids"—thin, translucent barriers that trapped geothermal heat and solar energy, creating a "solid-state greenhouse" that kept the water liquid for millions of years, even as the world above froze.

This is the story of how ice saved the water on Mars, and how it might have preserved life itself.

Part I: The Paradox of the Faint Young Sun

To understand the magnitude of the "Ice Shield" discovery, we must first confront the central mystery of Martian climatology: the Faint Young Sun Paradox.

In the 1970s, astronomers Carl Sagan and George Mullen identified a problem that applied to both Earth and Mars. Stellar evolution models show that stars like our Sun grow brighter as they age. Four billion years ago, during the Noachian period of Mars (roughly 4.1 to 3.7 billion years ago), the Sun was about 30% dimmer than it is today. On Earth, a thick atmosphere of greenhouse gases likely compensated for this, keeping our oceans liquid. But Mars is further away, receiving less than half the solar energy Earth does.

If you plug the parameters of the ancient Sun and Mars’s orbital distance into a standard climate model, the result is unequivocal: the average global temperature of Mars should have been around -48°C (-54°F). At these temperatures, water is rock-hard ice. There are no rivers, no lakes, no rainfall.

The Geological contradictionYet, the geology of Mars tells a completely different story.

- Valley Networks: Thousands of branching channels, similar to river systems on Earth, dissect the ancient southern highlands.

- Crater Lakes: Over 200 paleolakes have been identified. Some, like Jezero Crater (the landing site of the Perseverance rover) and Gale Crater, show clear inlet and outlet channels, indicating water flowed in, filled the basin, and spilled over the rim.

- Mineralogy: The surface is rich in phyllosilicates (clays) and sulphates—minerals that form exclusively in the presence of liquid water. Specifically, the discovery of kaolinite clays, which require intense leaching by rain or meltwater, suggests a hydrological cycle that was active for extended periods.

For years, the scientific community was split into two camps.

- The "Warm and Wet" Camp: This group argued that ancient Mars must have had a massive, dense atmosphere of carbon dioxide (CO2) and perhaps hydrogen (H2) or methane (CH4) that created a super-greenhouse effect, raising temperatures above freezing and allowing for rain and blue oceans.

- The "Cold and Icy" Camp: Led by researchers like Robin Wordsworth at Harvard, this group argued that the atmospheric chemistry required to warm Mars was unstable and unrealistic. They proposed a "Snowball Mars" where the planet was mostly frozen, with transient melting events caused by meteor impacts or volcanic eruptions.

The "Warm and Wet" model struggled to explain why we don't see massive deposits of carbonate rocks (which should form if there was that much CO2). The "Cold and Icy" model struggled to explain features that require sustained water flow, like meandering rivers and deep lake sediments, which take thousands of years to form, not just a few weeks after a meteor strike.

Part II: The Breakthrough – The Seasonal Ice Lid

In early 2026, a team from Rice University, led by planetary scientist Eleanor Moreland, published a study that fundamentally shifted the debate. They didn't try to force the atmosphere to be warmer. Instead, they looked at the thermodynamics of the lakes themselves.

Using a modified climate model adapted for Gale Crater, they tested a hypothesis inspired by lakes on Earth: What if the lake wasn't open water, but wasn't frozen solid either?

The Mechanics of the "Ice Shield"The team found that under cold Martian conditions, a lake surface would freeze. However, instead of freezing to the bottom (a "solid block" scenario), the lake could develop a seasonal ice lid.

- Thickness: This lid would be relatively thin—ranging from less than a meter to perhaps a few meters thick.

- Insulation: Ice is an excellent insulator. It prevents the water below from losing heat to the freezing atmosphere through evaporation (latent heat loss) and convection.

- The Solid-State Greenhouse Effect: This is the crucial mechanism. Clear or semi-transparent ice allows sunlight (visible wavelengths) to penetrate through to the water below. The water absorbs this solar energy and warms up. However, the ice is opaque to the infrared radiation (heat) that the water tries to emit back out. The heat is trapped.

This theory perfectly bridges the "Warm vs. Cold" divide.

- It acknowledges the "Cold and Icy" climate: It admits the air was freezing.

- It preserves the "Wet" geology: It allows for long-lived liquid water that can deposit sediments and sustain chemistry.

In this scenario, Mars wasn't a tropical world of rainstorms. It was a world of silent, ice-covered reservoirs. During the summer, the ice might thin or melt around the edges (creating "moats" of open water), allowing sediment to wash in. During the winter, the lid would thicken, sealing the lake. This explains why we see sedimentary layers in Gale Crater that imply millions of years of water history, without needing an impossible atmosphere.

Part III: Earth’s Icy Mirrors – Analogues for Ancient Mars

To visualize this ancient Martian environment, we don't need to look at science fiction. We can look at Earth.

1. Antarctic Subglacial Lakes (Lake Vostok & Lake Whillans)Deep beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet lies Lake Vostok, a body of water the size of Lake Ontario, buried under 4 kilometers of ice. It has been sealed off from the atmosphere for 15 million years.

- Heat Source: It stays liquid due to geothermal heat from below and the immense pressure of the ice above, which lowers the freezing point.

- Relevance: While Vostok is a "thick ice" scenario, it proves that liquid water can persist in the coldest environments on Earth. More relevant to the "seasonal lid" theory are the Dry Valley Lakes (e.g., Lake Hoare, Lake Bonney). These lakes have permanent ice covers about 4-6 meters thick. Despite the air temperature averaging -20°C, the water below is liquid and teeming with microbial life. The ice acts exactly as the Rice University model predicts for Mars: a window for light, a wall for heat.

In the Chilean Andes, lakes like Laguna Licancabur sit at high altitudes where UV radiation is intense (like Mars) and temperatures swing wildly. These lakes are often ice-covered but liquid. They serve as perfect laboratories for understanding how life copes with the "ice shield" environment.

3. The Tibetan PlateauRecent studies of lakes on the Tibetan Plateau have shown that thin ice covers can actually accelerate the warming of the water below in spring. The ice prevents the wind from mixing the water and cooling it down, allowing the sun to heat the top layer of water rapidly. This "solar trap" effect would have been a lifeline for ancient Martian lakes.

Part IV: The Detectives of the Deep – The South Pole Controversy

While the Rice University study focuses on ancient lakes, a parallel scientific drama has been unfolding regarding modern liquid water on Mars. This story highlights just how difficult it is to interpret signals from beneath the ice.

The Discovery (2018):The European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter, equipped with the MARSIS radar, detected a bright reflective area 1.5 km beneath the South Polar Layered Deposits (SPLD). The signal was intense—so bright that the team, led by Roberto Orosei, concluded it could only be liquid water. They proposed a 20km-wide subglacial lake, likely a hypersaline brine (salty water) kept liquid by dissolved perchlorates.

The Skepticism (2019-2021):The planetary science community was electrified but cautious. To keep water liquid at that depth without volcanic heat, you would need an incredible amount of salt.

Then came the counter-arguments:

- The Clay Hypothesis: In 2021, researchers including Isaac Smith demonstrated that smectites (a type of frozen clay common on Mars) could produce the exact same radar reflection as liquid water if they were hydrated and frozen at very low temperatures.

- Conductive Ice: Other papers suggested that variations in the electrical conductivity of the ice itself could mimic a lake signal.

New data from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) using the SHARAD radar—which operates at a higher frequency than MARSIS—failed to see the bright reflection. If it were a massive lake of pure brine, SHARAD should likely have seen it too. This non-detection swung the consensus back toward the "Clay/Smectite" explanation or perhaps "slush" rather than a clear lake.

The Connection:Why does this modern controversy matter for ancient Mars? It teaches us that "following the water" is tricky.

- If the South Pole signal is clay, it means Mars is likely dry and frozen deep down today.

- If it is water (perhaps localized pockets of slush), it implies that geothermal heat is still active.

- Crucially, the "smectites" found at the pole are the same minerals found in Gale Crater. They are the chemical ghosts of the ancient water. The clays under the South Pole might be the frozen fossil of a lake that existed billions of years ago, preserved by the ice shield until it eventually froze completely.

Part V: Life in the Freezer

If ancient Mars had ice-covered lakes for millions of years, could life have survived there? The answer from Earth’s biology is a resounding "Yes."

The "Ice Shield" environment is actually better for life than an open lake on a thin-atmosphere planet.

- UV Protection: Mars lacks an ozone layer. The surface is bombarded by DNA-destroying ultraviolet radiation. A layer of ice, even just a few meters thick, absorbs almost all harmful UV radiation while letting visible light (used for photosynthesis) pass through.

- Stability: Open water on Mars would be unstable, boiling off or freezing rapidly. An ice-covered lake is a stable, pressurized environment.

To imagine what lived in Gale Crater, we look at psychrophiles (cold-loving microbes).

- ---Planococcus halocryophilus---: Discovered in the Canadian High Arctic permafrost, this bacterium is a champion of the cold. It remains metabolically active at -25°C and can reproduce at -15°C. It survives by altering its cell membrane to remain fluid in the cold and producing "antifreeze proteins" that bind to ice crystals and stop them from growing inside the cell. It builds a "calcium carbonate" shell—essentially a microscopic spacesuit. If we find fossils on Mars, they might look like the calcified remains of Planococcus.

- ---Psychromonas ingrahamii---: Found in Arctic sea ice, this bacterium grows exponentially at -12°C. It has a generation time (doubling time) of 240 hours. On Mars, where life would need to be patient, "slow and steady" is a winning strategy.

- Antifreeze Proteins (IBPs): These are the molecular keys to the kingdom. Organisms like the yeast Glaciozyma produce proteins that attach to the face of an ice crystal. This creates "thermal hysteresis"—a gap between the freezing point and the melting point. It effectively lowers the freezing point of the water inside the microbe, allowing it to swim through liquid brine veins within the ice.

In the "Ice Shield" model of ancient Mars, the lake bottom would likely be carpeted with microbial mats. These sticky, layered communities would feed on chemical energy from the sediments (chemolithotrophy) or dim sunlight filtering through the ice (photosynthesis). They would be safe from the harsh radiation and the freezing wind, thriving in a quiet, dark, cold oasis.

Part VI: The Future – Drilling Through the Looking Glass

The "Ice Shield" theory has given mission planners a new roadmap. We no longer just look for "ancient shorelines"; we look for the subtle signs of ice-contact sedimentation.

1. The Rosalind Franklin Rover (ExoMars)Launching later this decade, the ESA’s Rosalind Franklin rover is the most exciting hunter in this game. Unlike Curiosity or Perseverance, which drill only a few centimeters, Rosalind Franklin carries a drill capable of reaching 2 meters (6.5 feet) deep.

- Why 2 meters? This depth gets below the "radiation zone" where cosmic rays destroy organic molecules. It reaches the pristine, frozen subsurface.

- Instruments: It carries Ma_MISS, a spectrometer inside the drill tip, allowing it to analyze the borehole walls in real-time. It also carries MOMA (Mars Organic Molecule Analyser), which can detect the "handedness" (chirality) of amino acids—a smoking gun for biological origin. If ancient microbes lived under an ice shield and died there, their chemical signatures might still be frozen 2 meters down.

This proposed mission (a collaboration between NASA, CSA, JAXA, and ASI) aims to send a high-frequency synthetic aperture radar (SAR) to orbit Mars. Its goal: to map the top 10 meters of the subsurface at high resolution. It will look for massive clean ice sheets in the mid-latitudes—the remnants of the last great ice age—but it will also help identify the interfaces between rock, ice, and regolith that could verify the "ice shield" geological models.

3. Mars Sample ReturnThe ultimate proof lies in the rocks. NASA’s Perseverance rover has been collecting chalk-sized cores of rock from Jezero Crater. Some of these samples are from the delta, where clays and carbonates are found. If these rocks contain the fossilized remains of "cold-shock" proteins or specific lipid membranes used by psychrophiles, we will know that Mars wasn't just wet—it was alive.

Conclusion: A World of White and Blue

The image of ancient Mars is changing. We are moving away from the "Blue Mars" of terraforming fantasies—a warm, Earth-like twin with crashing waves and rain forests. The reality is perhaps more subtle and more resilient.

Ancient Mars was likely a "White Mars" with veins of blue. A planet of freezing winds and encroaching glaciers, where life didn't conquer the surface, but retreated into the sanctuaries of the ice. The "Ice Shields" of Gale Crater and Jezero were not coffins; they were cradles. They preserved the liquid water that was the planet's most precious resource.

As we look to the future, to the human explorers who may one day drill into these ancient lakebeds, we carry a new understanding. We are not looking for a failed Earth. We are looking for a successful Mars—a planet that found a way to keep its heart liquid, even as its skin turned to ice. And deep down, protected by the shields of the past, the chemical faint signatures of that endurance might still be waiting for us.

Reference:

- https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/nai/annual-reports/2015/mit/mars-analog-studies-ice-covered-lakes-on-earth-and-mars/index.html

- https://tc.copernicus.org/research_article.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ATtEgal_mOI

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343846614_Can_Halophilic_and_Psychrophilic_Microorganisms_Modify_the_FreezingMelting_Curve_of_Cold_Salty_Solutions_Implications_for_Mars_Habitability

- https://blogs.esa.int/to-mars-and-back/2025/02/26/drilling-into-mars/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fnMa6TDyRYE

- https://www.lightsource.ca/public/news/pre-apr-2019/2015/sub-zero-bacteria-from-canadas-north-could-indicate-life-on-mars.php

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14994177/

- https://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu/bionumber.aspx?s=n&v=4&id=106268

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2405808/

- https://www.universetoday.com/articles/exomars-will-be-drilling-1-7-meters-to-pull-its-samples-from-below-the-surface-of-mars

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361381090_Exploring_the_Shallow_Subsurface_of_Mars_with_the_Ma_MISS_Spectrometer_on_the_ExoMars_Rover_Rosalind_Franklin

- https://search.asi.it/entities/publication/68445a07-5186-4c6f-a59f-2b73264bc94f