Here is a comprehensive and engaging article detailing the resurrection of the lost orchestra of Wuwangdun.

The Chu Symphony: Resurrecting the Lost Orchestra of WuwangdunIn the fertile lands of Huainan, Anhui Province, beneath layers of earth that have seen empires rise and fall for over two millennia, a silence has finally been broken. It is not the silence of the void, but a pregnant pause that has lasted since the twilight of the Warring States period. For centuries, historians and archaeologists have dreamed of the "Sound of Chu"—a musical tradition described in ancient texts as romantic, shamanistic, and wildly different from the rigid court rituals of the north. We knew it existed in the verses of the

Chu Ci (Songs of Chu), where poets sang of "zithers and pipes in frenzied assembly." But the physical reality of this lost symphony remained fragmented, a ghost drifting through the corridors of history.That changed with the excavation of Wuwangdun Tomb No. 1.

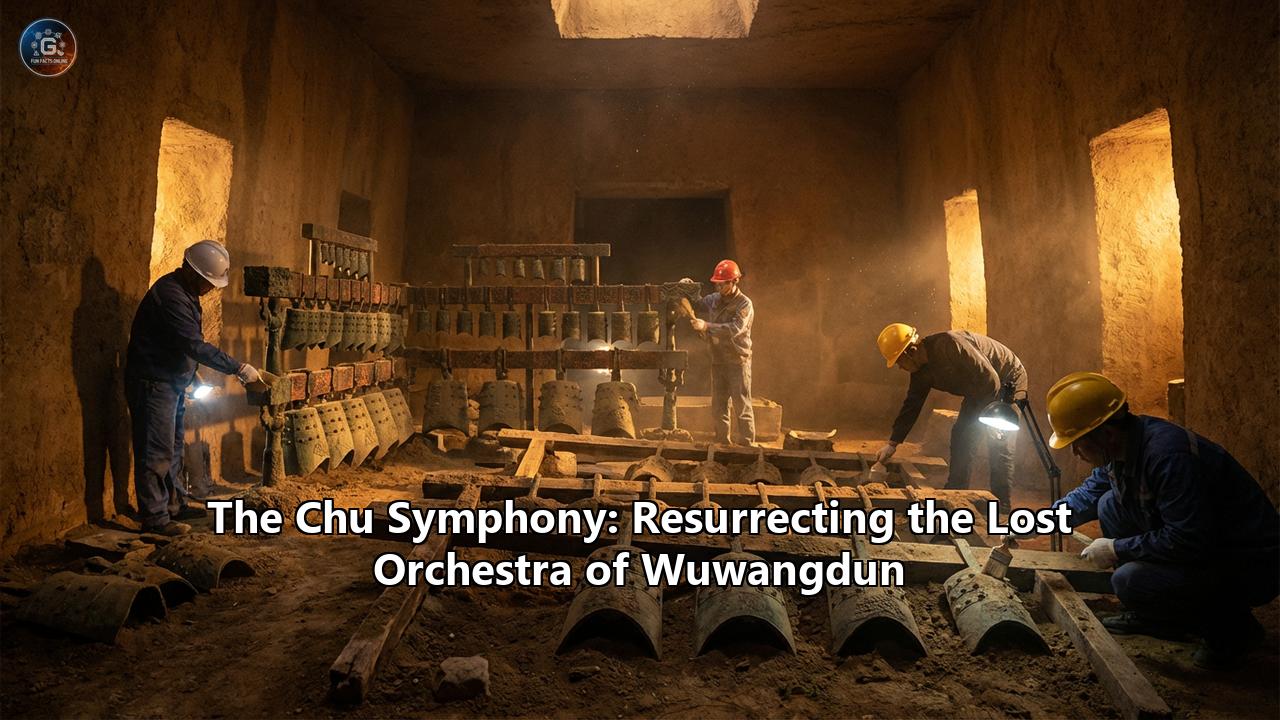

Confirmed in 2024 and 2025 to be the final resting place of King Kaolie of Chu (reigned 262–238 BC), this site is not merely a tomb; it is a time capsule sealed at the precise moment Chinese civilization was pivoting from the fractured feudalism of the Zhou to the imperial unity of the Qin and Han. Among the treasures of gold, jade, and bronze, the most breathtaking discovery is a sprawling, intricate, and miraculously preserved musical ensemble. This is the "Lost Orchestra" of Wuwangdun—a collection of over 50 instruments that allows us, for the first time, to fully reconstruct the soundtrack of a dying empire.

I. The Twilight King: The Man Behind the Music

To understand the orchestra, one must first understand the conductor of this silent symphony: King Kaolie.

The late Warring States period was an era of blood and iron. The State of Chu, once a sprawling southern giant that claimed equality with the Zhou kings, was in a slow, agonizing retreat. By the time Kaolie ascended the throne, the capital had been forced to move east to Shouchun (modern-day Huainan) to escape the relentless war machine of the Qin state.

Yet, as political power waned, artistic expression exploded. This is a common paradox in history: the "sunset glow" of a civilization often produces its most poignant art. King Kaolie’s court was a center of extravagant culture, dominated by powerful figures like the Lord of Chunshen, one of the famous "Four Lords of the Warring States." It was a world of high stakes, political intrigue, and deep superstition.

The Wuwangdun tomb reflects this duality. It is a massive, cross-shaped structure with a central burial chamber surrounded by eight side compartments—a layout of imperial ambition. But unlike the martial tombs of the Qin, Kaolie’s resting place is suffocated with the trappings of pleasure and ritual. He did not plan to conquer the afterlife; he planned to enchant it.

II. The Anatomy of the Orchestra

The musical cache found in Wuwangdun is the largest and most complex ever discovered in a Chu tomb. While the famous Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (excavated in 1978) gave us the colossal bronze bells that defined the early Warring States, Wuwangdun gives us the sound of the

end of the era. The difference is profound. The orchestra of Wuwangdun is lighter, more melodic, and dominated by strings and winds—a shift from the "heavy metal" ritualism of the past to a more personal, expressive musicality.Let us walk through the sections of this resurrected ensemble.

1. The King of Zithers: The Great Se

The centerpiece of the collection is the

Se (zither). Archaeologists uncovered over 50 of these instruments, a staggering number for a single tomb. But it is their size that defies belief. Some of these lacquered wooden zithers measure over 2.1 meters in length, earning them the title "King of Zithers."The

Se is an instrument of deep antiquity, often mentioned in the same breath as the Qin. However, while the Qin was the instrument of the solitary scholar, the Se was the engine of the ensemble. It was powerful, resonant, and complex. The Wuwangdun Se features 23 to 25 strings, each bridged by a movable wooden fret.Imagine the sound: a deep, thrumming bass overlaid with cascading pentatonic melodies. In the dim light of the excavation laboratory, as researchers cleaned the millennia-old mud from the black lacquer, they revealed intricate paintings of dragons and phoenixes coiling around the soundboard. These were not just instruments; they were vehicles for the soul.

The presence of 25-string zithers immediately brings to mind the famous poem by Li Shangyin:

"The Brocade Zither has fifty strings, no one knows why;

Each string, each bridge, recalls a year gone by."

Scholars have long debated this line. The discovery at Wuwangdun suggests that the "fifty strings" might have been a poetic doubling of the standard 25-string

Se, or perhaps a reference to a lost giant variant that Kaolie took to his grave.2. The Breath of Life: The Sheng and the Yu

If the

Se provided the body of the music, the Sheng and Yu provided its breath. The excavation yielded over 20 of these bamboo mouth organs, preserved in a waterlogged state that kept their delicate pipes intact.The

Sheng is familiar to us—it is the ancestor of the harmonica and the accordion, a cluster of bamboo pipes set into a gourd wind chest. But the Yu is the true star of this find. Larger, deeper, and more commanding than the Sheng, the Yu was the "leader" of the wind section in ancient times.Historically, the

Yu is famous for the idiom "filling the number" (lan yu chong shu), which tells of a man who couldn't play the instrument but pretended to in a 300-man ensemble to earn a salary. The Wuwangdun discovery puts this story into perspective. With so many Yu found in a single royal tomb, we can see that these were indeed played in large, "frenzied" groups.Crucially, the

Yu went extinct shortly after the Han dynasty. Its specific construction and playing technique were lost. The Wuwangdun artifacts, with their preserved reeds and pipes, offer the first real chance in 2,000 years to reverse-engineer the instrument and hear the bass-heavy drone that underpinned the Chu melodies.3. The Beat of the Phoenix: The Tiger-Seated Drum

No object screams "Chu Culture" quite like the Tiger-Seated Bird-Frame Drum (

Hu Zuo Niao Jia Gu). This is a purely southern instrument, unknown in the rigid courts of the Yellow River valley.The visual is striking: two crouching tigers, painted in red and black lacquer, serve as the base. Standing on their backs are two magnificent phoenixes (or cranes), their long necks arching upward to suspend a large drum between them.

The symbolism is potent. In Chu mythology, the tiger represents the earth and physical power—and perhaps the spirits of the underworld. The phoenix represents the sky, transcendence, and the ascent of the soul. By suspending the drum between them, the musician becomes the mediator between heaven and earth, beating a rhythm that bridges the gap between the living and the dead.

The Wuwangdun example is the largest and most exquisitely decorated ever found. It likely served as the rhythmic heart of the shamanistic rituals that defined Chu religion, where music was used to induce trances and invite deities to descend.

4. The Echo of Ritual: Bronze and Stone Chimes

While the orchestra is dominated by strings and winds, the old gods were not forgotten. The tomb contained two sets of 23 bronze bells and a set of 20 stone chimes.

However, a comparison with the Marquis Yi tomb (dated roughly 200 years earlier) reveals a fascinating evolution. Marquis Yi’s tomb was dominated by a massive 65-bell carillon that required five people to play. King Kaolie’s bells are smaller and fewer.

This does not imply poverty—Kaolie was a King, Yi only a Marquis. Instead, it signals a change in taste. By the late Warring States, the heavy, slow-moving ceremonial music of the Western Zhou was falling out of fashion. It was being replaced by

Xin Yue (New Music)—faster, louder, more emotional, and driven by the interplay of silk strings and bamboo pipes. The bells in Wuwangdun were likely used for punctuation and ritual signaling rather than carrying the main melody.III. The Soundscape of the Soul: What Did It Sound Like?

Thanks to these discoveries, musicologists are beginning to piece together the "Chu Symphony."

Unlike the solemn, slow music of the Confucian north, the music of Chu was likely ecstatic and highly dynamic. The combination of multiple 2-meter-long

Se zithers playing together would create a "wall of sound"—a rich, reverberating texture of plucked notes. Over this, the Yu and Sheng would provide a continuous, swelling harmony (since mouth organs produce sound on both exhale and inhale, the sound never stops).Punctuating this would be the thunderous strike of the Tiger-Seated Drum and the shimmering crash of the stone chimes.

The ancient poet Qu Yuan, a minister of Chu who lived just decades before King Kaolie, described such a scene in the

Zhao Hun (Summons of the Soul):"The pipes and zithers rise in wild harmony,

The drums thunder, shaking the hall.

The singers chant the songs of the south,

While dancers in silk whirl like the wind."

For centuries, these lines were just poetry. With the Wuwangdun excavation, we now have the physical props of this performance. We can see the lacquerware wine cups that would have been passed around; we can hold the bamboo flutes that accompanied the dancers. We are not just looking at objects; we are looking at a frozen party, a feast for the ghosts that has waited 2,200 years to resume.

IV. The Miracle of Preservation

The resurrection of this orchestra is a triumph of modern archaeology. When the tomb was opened, the wooden instruments were waterlogged—soft as cheese and dark as mud. In the past, such items might have shrunk and disintegrated upon contact with air.

However, the Wuwangdun project utilized a low-oxygen archaeological laboratory built directly over the excavation site. Researchers worked in controlled environments, using infrared imaging to read the ink inscriptions on the coffin boards before they could fade. These inscriptions have been crucial, providing an inventory of the tomb's contents and, in some cases, the names of the chambers.

The "Music Chamber" was identified not just by the instruments, but by the layout of the artifacts. The careful placement suggests that the orchestra was not just "stored" but "staged," ready to be played by the wooden figurines found nearby, representing the musicians who would serve the King in the afterlife.

V. A Bridge to the Han Dynasty

The Wuwangdun discovery fills a critical "missing link" in Chinese music history. Before this, we had the early Warring States bells (Marquis Yi) and the Han Dynasty pottery figurines of musicians. Wuwangdun sits right in the middle.

It shows the transition from the Bronze Age logic of "bells and drums" to the Iron Age logic of "silk and bamboo." This shift mirrors the political changes. As the old feudal order collapsed and the centralized empire rose, music became less about marking social hierarchy (the number of bells you owned) and more about entertainment, emotion, and personal expression.

The instruments found here are the direct ancestors of the music played at the Han imperial court—the music that would define "Chinese" culture for the next four centuries. The

Se and Yu found here are the "grandfathers" of the Guzheng and Sheng* played today.VI. Conclusion: The Song Continues

The excavation of Wuwangdun is ongoing, and conservation of these delicate instruments will take years. But the initial findings have already rewritten the textbooks. We have resurrected a lost orchestra.

King Kaolie may have failed to save his kingdom from the Qin armies; Chu fell in 223 BC, just 15 years after his death. But in the darkness of Wuwangdun, his culture survived. The "Chu Symphony" captures a moment of dazzling brilliance before the end—a civilization celebrating its identity, its mythology, and its romance through wood, silk, and bronze.

As we gaze upon the Tiger-Seated Drum and the giant Zithers, we are reminded that while empires turn to dust, music—the most ephemeral of arts—can, with a little luck, echo forever. The lost orchestra is playing again, and the world is finally listening.

Reference:

- http://english.cssn.cn/skw_culture/202504/t20250417_5869640.shtml

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_Marquis_Yi_of_Zeng

- https://english.news.cn/20240420/01e66ac6cdeb4ac4bd7101f836d3c648/c.html

- https://www.huainan.gov.cn/HUAINANCHINA/News/1260568891.html

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/ancient-tomb-china-warring-states-period

- https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-marquis-yi-of-zeng-%C4%B1-bronze-objects-hubei-provincial-museum-%E6%B9%96%E5%8C%97%E7%9C%81%E5%8D%9A%E7%89%A9%E9%A6%86/qAVhJ6vlhDe4Lg?hl=en

- https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202512/1351217.shtml

- https://www.penn.museum/sites/journal/1401/

- https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/202309/12/WS65000b20498ed2d7b7e9acde/delicately-designed-black-lacquered-drum-from-over-2-000-years-ago.html

- https://www.vantagemusic.org/magazine/qu-yuans-nine-songs/