When the daytime sky begins to dim, taking on an eerie, silvery metallic pallor, and the shadows on the ground sharpen into strange, crescent-like projections, human instinct dictates that something profound is happening in the heavens. For millennia, the darkening of the Sun was viewed with primal terror, interpreted as a cosmic omen or the work of mythological beasts devouring the light. Today, we understand the celestial mechanics at play, yet the awe remains entirely undiminished.

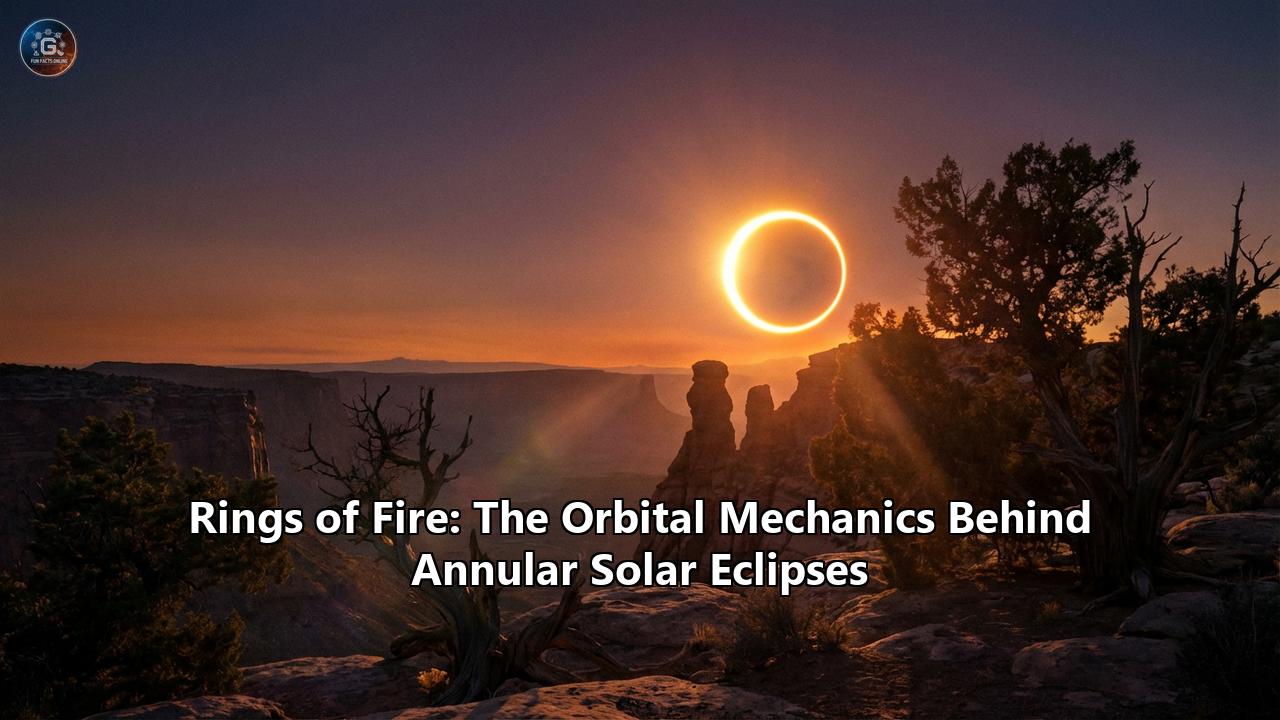

Among the various types of solar eclipses, one of the most hypnotic and mathematically fascinating is the annular solar eclipse—widely known as the "Ring of Fire". Unlike a total solar eclipse, where the Moon completely obscures the Sun and plunges the Earth into an abrupt, localized night, an annular eclipse leaves a brilliant, blazing halo of solar plasma entirely visible around the dark silhouette of the Moon.

This breathtaking spectacle is not the result of a cosmic error, but rather a flawless demonstration of orbital mechanics, gravitational physics, and the elegant, elliptical geometry of our solar system. To truly understand the "Ring of Fire," one must look beyond the visual majesty of the event and dive deep into the clockwork of the cosmos.

The Great Celestial Coincidence and Its Limitations

To understand any solar eclipse, we must first appreciate the staggering architectural coincidence of our local neighborhood. The Sun's physical diameter is roughly 1.4 million kilometers, which makes it about 400 times wider than our Moon, whose diameter is a mere 3,474 kilometers. However, by a stroke of sheer planetary serendipity, the Sun is also, on average, exactly 400 times further away from the Earth than the Moon is.

Because of this 400-to-1 ratio in both size and distance, the Sun and the Moon appear to be almost exactly the same size in our terrestrial sky. In astronomical terms, they both have an average "angular diameter" of about half a degree (or 30 arcminutes).

If the universe were governed by the idealized, perfect circles envisioned by ancient Greek philosophers like Ptolemy and Aristotle, the Moon would always appear exactly the same size, and every central eclipse would be a total eclipse. The Moon would slide perfectly over the Sun, like a bespoke cosmic coin, every single time. But the universe is not bound by perfect circles. It is governed by gravity, momentum, and the laws of planetary motion discovered by Johannes Kepler in the early 17th century.

Kepler’s Ghost: The Dance of the Ellipses

Kepler’s First Law of Planetary Motion states that all orbits are ellipses, not perfect circles, with the primary body located at one of the two focal points of the ellipse. Because orbits are slightly stretched and oval-shaped, the distances between celestial bodies are in a constant state of flux. This variation in distance is the fundamental engine that drives the annular solar eclipse.

Let us first examine the orbit of the Earth around the Sun. The Earth's orbit has an eccentricity (a measure of how much it deviates from a perfect circle) of about 0.0167. This means that once a year, the Earth reaches its closest point to the Sun, known as perihelion. At perihelion, which currently occurs in early January, the Earth is approximately 147.1 million kilometers from the Sun. Six months later, in early July, the Earth reaches aphelion, its furthest point, sitting roughly 152.1 million kilometers away. Because of this 5-million-kilometer difference, the Sun's apparent size in our sky swells slightly in January (reaching about 32.7 arcminutes) and shrinks in July (down to about 31.6 arcminutes).

Now, we must layer the Moon's orbit onto this moving canvas. The Moon's orbit around the Earth is considerably more eccentric than the Earth's orbit around the Sun, with an eccentricity of 0.0549. During its 27.5-day orbital period, the Moon swings through its closest approach to Earth, called perigee, and its furthest point, called apogee.

At an extreme perigee, the Moon can come as close as roughly 356,400 kilometers to Earth, appearing massive in our sky (a phenomenon popular media often dubs a "Supermoon"). But at an extreme apogee, the Moon retreats to a distance of over 406,700 kilometers. At this distant vantage point, known colloquially as a "Micromoon," the lunar disk's angular diameter shrinks to just 29.3 arcminutes.

The genesis of a "Ring of Fire" requires a specific interplay between these fluctuating distances. An annular solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes directly in front of the Sun while it is at or near apogee. Because the Moon is unusually far from the Earth, it appears too small to cover the entire solar disk. The effect is particularly pronounced if the eclipse occurs near Earth's perihelion (January/February), when the Sun appears at its absolute largest. The result is a mathematically precise gap—a brilliant annulus of the Sun's photosphere screaming out around the edges of the lunar silhouette.

The Geometry of Shadows: Umbra, Penumbra, and the Antumbra

To visualize why an annular eclipse looks the way it does from the ground, we must map the anatomy of the lunar shadow as it is cast through the vacuum of space. When the Sun illuminates the Moon, the Moon casts a shadow complex made of distinct geometric zones.

- The Penumbra: The pale, outer cone of the shadow. From within the penumbra, the Moon only partially blocks the Sun. Anyone standing in the path of the penumbra will witness a partial solar eclipse.

- The Umbra: The dark, inner, tapering cone where all direct sunlight is entirely blocked. If the Moon is close enough to Earth (near perigee), the tip of this umbral cone reaches the Earth's surface. Observers in this path experience a total solar eclipse.

- The Antumbra: This is the secret ingredient of the Ring of Fire. Because the umbra is a narrowing cone, it eventually comes to a point and ends. If the Moon is at apogee, the tip of the umbral cone runs out of real estate; it tapers off into nothingness before it reaches the surface of the Earth. However, the shadow geometry continues to project outward past this focal point, expanding into an inverted cone known as the antumbra.

When the antumbra sweeps across the Earth's surface, it carves out the "path of annularity". If you are standing inside the antumbra, you are looking straight up through the mathematical focal point where the umbra ended, past the edges of the Moon, and directly into the unblocked outer margins of the Sun.

The Tilted Orbit and the Nodes of Syzygy

Given that the Moon orbits the Earth every month, passing between the Earth and the Sun during every "New Moon" phase, one might assume we should have a solar eclipse every four weeks. The reason we do not is due to another critical piece of orbital architecture: orbital inclination.

The Moon does not orbit the Earth on the exact same flat, two-dimensional plane that the Earth orbits the Sun (known as the ecliptic plane). Instead, the Moon's orbit is tilted by approximately 5.14 degrees relative to the ecliptic. While 5 degrees may sound negligible, over the vast distance of 380,000 kilometers, it is more than enough to ensure that the Moon's shadow usually sails millions of kilometers above the Earth's North Pole or dips far below the South Pole.

For an eclipse to occur, the New Moon must happen precisely when the Moon is crossing the ecliptic plane. These two points of intersection—where the Moon's orbit plunges down through the ecliptic or rises up through it—are called the lunar nodes (the descending node and the ascending node).

When the Sun, Earth, and Moon achieve perfect spatial alignment along these nodes, astronomers call the event syzygy (from the ancient Greek word syzygos, meaning "yoked together"). Because the nodes slowly rotate over time, syzygy occurs during specific "eclipse seasons," which happen roughly every six months. During these windows, the geometry is perfectly primed to cast shadows onto the Earth.

The Clockwork of the Ancients: The Saros Cycle

One of the most astonishing aspects of orbital mechanics is that it is fundamentally rhythmic. Long before the invention of telescopes or the formulation of Newtonian physics, ancient astronomers—most notably the Babylonians—realized that eclipses were not random acts of angry gods. They followed a predictable, repeating mathematical pattern known as the Saros cycle.

The Saros cycle is the result of three different lunar months harmonizing like the gears of a cosmic grandfather clock:

- The Synodic Month (29.53 days): The time it takes for the Moon to cycle through its phases (e.g., from New Moon to New Moon).

- The Draconic Month (27.21 days): The time it takes for the Moon to return to the same orbital node (crossing the ecliptic).

- The Anomalistic Month (27.55 days): The time it takes for the Moon to travel from perigee to perigee (or apogee to apogee).

Every 18 years, 11 days, and 8 hours, these three cycles sync up almost perfectly. (Specifically, 223 synodic months equals 242 draconic months, which also equals 239 anomalistic months).

Because the anomalistic month is factored into this equation, the Moon is at the exact same distance from the Earth at the end of a Saros cycle as it was at the beginning. Therefore, not only does an eclipse repeat every 18 years and 11 days, but the type of eclipse repeats as well. An annular eclipse will birth another annular eclipse. A total eclipse will birth another total eclipse.

However, because of the extra 8 hours in the Saros cycle, the Earth has rotated an additional one-third of the way on its axis when the next eclipse occurs. This means the path of the eclipse is shifted roughly 120 degrees westward on the globe. It takes three full Saros cycles (54 years and 34 days)—a period known as an exeligmos—for an eclipse to repeat in the same general geographic region of the world.

A Tour of Upcoming Annular Spectacles

The celestial mechanics described above are not just abstract theories; they paint magnificent paths of shadows across our planet in real time. Over the coming years, a series of remarkable annular solar eclipses will grace the Earth, each one dictated by the exact distance of the Moon's apogee.

The Antarctic Ring of Fire: February 17, 2026In an incredible demonstration of how the tilt of the Earth and the orbital nodes interact, a breathtaking annular eclipse will sweep across the icy, desolate expanses of Antarctica on February 17, 2026. Because this occurs in the southern hemisphere's late summer, the path of annularity stretches 2,661 miles across the frozen continent and the Southern Ocean. The Moon will obscure up to 96% of the Sun's center, creating a Ring of Fire lasting up to 2 minutes and 20 seconds. Because of the extreme remoteness of the path, humanity's view of this event will be largely limited to a handful of intrepid scientists stationed at research bases like Concordia and Mirny.

The Equatorial Traverse: February 6, 2027Just shy of a year later, the orbital mechanics will realign for another annular eclipse, this time sweeping across highly populated regions. On February 6, 2027, the antumbra will touch down and carve a path over South America and West Africa, passing over nations including Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Nigeria. Because the Moon will be near a deep apogee, the Ring of Fire will be spectacular, visible to millions.

The Spanish-American Annulus: January 26, 2028Continuing the celestial show, an annular solar eclipse on January 26, 2028, will create a trans-Atlantic spectacle. The path of annularity will cross Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, and Suriname before traversing the ocean to plunge across Spain and Portugal. For regions in southern Spain, this represents a miraculous astronomical lottery: they will experience a total solar eclipse in August 2027, followed immediately by this annular solar eclipse just six months later in January 2028—a phenomenally rare geographic coincidence.

Experiencing the Annulus: Phenomena on the Ground

For those lucky enough to stand within the path of annularity, an annular eclipse is an entirely different sensory experience than a total eclipse. Because the Sun's blinding photosphere is never completely covered, the sky does not plunge into the deep, star-studded twilight of totality. The Sun's delicate corona—the wispy outer atmosphere that becomes visible during a total eclipse—remains entirely hidden, overwhelmed by the fierce light of the exposed solar ring.

Instead, the landscape is bathed in a profoundly alien light. As the Moon eats away at the Sun, the quality of daylight changes. It loses its warmth, taking on an ashen, steel-gray hue. Shadows sharpen dramatically, and the ambient temperature can drop noticeably as the Earth's primary heat source is significantly blocked.

One of the most enchanting phenomena occurs under the canopy of trees. The overlapping leaves act as thousands of natural pinhole cameras. During an annular eclipse, the dappled sunlight on the ground transforms into a carpet of thousands of perfect, miniature Rings of Fire.

As the Moon achieves perfect centralization, an effect known as Baily’s Beads can occasionally be observed at the extreme inner edge of the ring. The Moon is not a smooth, perfect billiard ball; it is a rugged world of towering mountains and deep impact craters. As the edge of the Moon grazes the inner edge of the Sun, the sunlight streams through the deep lunar valleys and is blocked by the lunar peaks, breaking the Ring of Fire into a fractured, sparkling necklace of light.

A critical caveat for the observer: Because the Sun's surface is never completely covered, there is no phase of an annular eclipse that is safe to view with the naked eye. The Ring of Fire emits more than enough ultraviolet and infrared radiation to cause permanent retinal damage. Certified solar viewing glasses or indirect viewing methods must be used for the entire duration of the event.Deep Time: The Extinction of Totality and the Era of the Annulus

When we marvel at a Ring of Fire today, we are witnessing a snapshot in a massive, slow-motion evolution of our solar system. The 400-to-1 cosmic coincidence that allows for both total and annular eclipses is not a permanent fixture. It is a temporary privilege of the epoch in which humanity happens to exist.

The Moon is slowly but inexorably running away from us.

As the Earth rotates, the gravitational pull of the Moon drags the Earth's oceans into tidal bulges. However, because the Earth rotates faster than the Moon orbits, the Earth's rotation drags these tidal bulges slightly ahead of the Moon. The mass of these water bulges exerts a gravitational tug on the Moon, pulling it forward in its orbit and accelerating it. As the Moon gains orbital energy, it spirals further away from the Earth at a rate of approximately 3.8 centimeters (1.5 inches) per year.

Over human lifespans, 3.8 centimeters is negligible. But in the grand calculus of deep time, it is apocalyptic for the total solar eclipse. Millions of years ago, during the era of the dinosaurs, the Moon was much closer to the Earth. It appeared vastly larger in the sky, meaning annular eclipses were incredibly rare, if not non-existent. Almost every central eclipse the dinosaurs lived under was a massive, long-lasting total eclipse.

As the Moon continues its outward drift, its apparent angular diameter in our sky is slowly shrinking. A straight mathematical projection tells a sobering story: in approximately 650 million to 1.2 billion years, the Moon will have drifted too far from the Earth to ever fully cover the Sun's disk, even when the Moon is at its closest possible perigee and the Earth is at its furthest aphelion.

When that distant day arrives, the total solar eclipse will go permanently extinct. The Moon's shadow will taper out into space, its umbra never again brushing the surface of our planet. From that point forward until the Sun expands into a red giant and swallows the Earth billions of years later, every single central eclipse experienced on our world will be an annular solar eclipse. The Ring of Fire will inherit the Earth.

The Harmonious Clockwork

The annular solar eclipse is a masterclass in cosmic physics. It requires a universe that is dynamic, not static. It requires elliptical orbits that stretch and breathe, orbital planes that tilt and intersect, and the relentless, invisible tether of gravity operating across millions of miles of empty space.

When you stand in the antumbra and look up at the Ring of Fire, you are not just looking at a beautiful alignment of light and shadow. You are looking at the mathematics of Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton written in fire across the sky. You are witnessing the exact, fleeting balance of the Earth's perihelion and the Moon's apogee. And you are sharing a brief, spectacular moment with a celestial companion that is slowly drifting away into the dark, reminding us that in the universe, nothing—not even the shadows—lasts forever.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_eclipse

- https://wklw.com/vip-inside-story/?id=146175&category=weather-nerd

- https://evrimagaci.org/gpt/antarctic-ring-of-fire-eclipse-coincides-with-global-holidays-529728

- https://astropixels.com/ephemeris/perap2001.html

- https://www.almanac.com/content/what-aphelion-and-perihelion

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apsis

- https://astropixels.com/ephemeris/moon/moonperap1601.html

- https://www.almanac.com/perigee-and-apogee

- https://www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/moon/lunar-perigee-apogee.html

- https://skycaramba.com/moon_perigees_apogees.shtml

- https://nationaleclipse.com/maps_upcoming.html

- https://www.almanac.com/eclipses

- https://www.timeanddate.com/eclipse/list.html

- https://science.nasa.gov/eclipses/future-eclipses/

- https://eclipse262728.es/en/eclipse2028/

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/quora/2018/01/11/as-the-moon-drifts-slowly-away-from-earth-will-there-eventually-be-a-last-total-solar-eclipse/