It was not until January 2026 that the stone finally gave up its ghost.

In a collision of 18th-century naturalism and 21st-century particle physics, a team of researchers from Friedrich Schiller University Jena and the German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg turned the blindingly bright light of a synchrotron particle accelerator onto the poet’s collection. They did not cut the amber. They did not polish it. Instead, they used X-rays a billion times brighter than the sun to digitally strip away the millions of years of oxidation and resinous cloud.

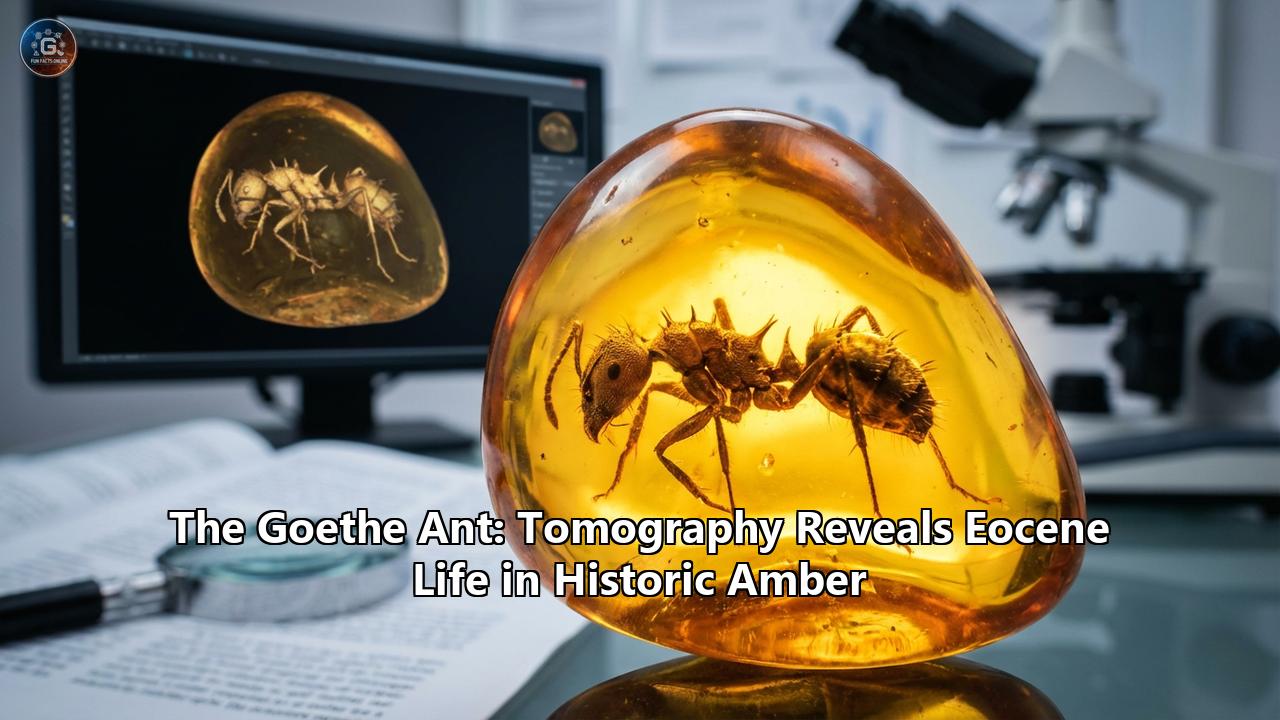

What emerged from the digital gloom was not just a speck of dust, but a biological masterpiece: a perfectly preserved, 40-million-year-old ant of the extinct species Ctenobethylus goepperti. The preservation was so exquisite that for the first time in the history of Cenozoic paleontology, scientists could peer inside the fossilized insect to map its internal muscle attachments and skeletal framework.

This is the story of "The Goethe Ant"—a discovery that bridges the gap between the Romantic era’s search for meaning and the Information Age’s ability to see the unseen. It is a journey that takes us from the wood-paneled study of Germany’s greatest writer to the lush, subtropical canopies of the Eocene epoch, and finally, to the cutting edge of digital morphology.

Part I: The Poet’s Stone

The Collector of Weimar

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is remembered by history primarily as a titan of literature. His words defined the Sturm und Drang movement; his plays and poems are the bedrock of the German language. But to Goethe himself, his scientific pursuits were not merely hobbies—they were an essential part of his being. "I do not fear that I shall be accused of contradicting myself," he once wrote, "if I confess that I have written as much about the granite as about the tragedy."

Goethe viewed science and art as two lungs of the same body. He coined the term morphology—the study of form—and spent his life obsessed with the idea of the Urpflanze (Primal Plant) and the Urwelt (Primal World). He believed that by studying the transition of forms, one could understand the underlying laws of nature. His collection in Weimar was the physical manifestation of this philosophy. It was not a "cabinet of curiosities" meant to dazzle with oddities; it was a study collection, rigorously organized to show the development of the earth.

The amber collection, comprising roughly 40 pieces, was a small but significant part of this archive. Goethe was fascinated by amber, which he called "an enduring fluid." He knew it was ancient tree resin, a mechanism of capture that froze moments of time. In Faust, he alludes to the mysteries hidden in the earth, and in his scientific writings, he often lamented the limitations of the human eye. He possessed a simple brass microscope, but the cloudy amber pieces in his drawer defied its low power. The particular piece housing the ant, labeled simply with the inventory number 1552.b, was dark, roughly textured, and filled with the milky nebulosity characteristic of "bastard amber."

Goethe likely picked it up, held it to the window light of his study on the Frauenplan, saw only a vague shadow, and placed it back in its box. He had explored the "explorable," as he famously said, and was now "quietly revering the inexplorable."

The Limits of Vision

For 200 years, piece 1552.b remained in the dark. The collection survived the death of Goethe in 1832, the upheaval of the Industrial Revolution, the rise and fall of the German Empire, the horrors of two World Wars, and the division of Germany. It sat in the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, protected as a cultural artifact but scientifically dormant.

In the world of paleontology, amber has always been a treasure trove. The Baltic region, specifically the Samland Peninsula (now Kaliningrad, Russia), holds the world’s largest deposits of succinite—amber formed from the resin of Eocene conifers. Since the 19th century, scientists have described thousands of species trapped in this golden matrix. However, the vast majority of these descriptions were based on "clear" amber. Specimens that were cloudy, opaque, or "dirty" were often discarded or ignored because traditional light microscopy—shining a light through the sample—simply didn't work. The light would scatter, obscuring the inclusion.

Goethe’s ant was a victim of this opacity. It was a ghost in a cloudy mirror, waiting for a light strong enough to shine through the fog.

Part II: The Synchrotron Beam

Light Brighter Than the Sun

The breakthrough came in early 2026, driven by a collaboration between the biological experts at the University of Jena and the physicists at DESY. The team, led by researchers who specialize in "digital morphology," proposed a new look at the old collection. They were not looking for new species per se; they were looking to prove a concept: that historical collections, even those centuries old and seemingly "empty," held data that only modern technology could unlock.

They transported the fragile amber pieces to Hamburg, home of the PETRA III synchrotron. A synchrotron is a particle accelerator that propels electrons near the speed of light through a storage ring. As these electrons are forced to change direction by magnetic fields, they emit energy in the form of incredibly intense X-rays.

Unlike a hospital CT scan, which is designed to see bones through flesh at a resolution of millimeters, synchrotron radiation-based micro-computed tomography (SR-µ-CT) can resolve details down to the micrometer—a thousandth of a millimeter. Furthermore, the "phase-contrast" imaging technique used at DESY is particularly sensitive to soft tissues. It detects not just how much X-ray energy is absorbed (density), but how the X-ray waves are shifted as they pass through different materials.

This was the key. The chitin of an ant’s exoskeleton and the fossilized resin of the amber have very similar densities. In a standard medical CT, they would look identical. But to the phase-contrast beam of the synchrotron, the subtle difference between the fossilized insect and the surrounding stone was as stark as black ink on white paper.

The Digital Dissection

The scan of piece 1552.b took only minutes, but the data processing took weeks. The computer algorithms reconstructed the X-ray projections into a three-dimensional volumetric model.

When the researchers finally rotated the digital model on their screens, the result was breathtaking. The cloudy amber melted away. Suspended in the digital void was a worker ant, its legs curled in the death pose, its antennae frozen in a final sensory sweep. It was not just a silhouette; it was a complete animal.

But the true shock came when they "sliced" the digital model. Usually, fossils in amber are hollow husks—the internal soft tissue rots away, leaving only a void shaped like the animal. Or, if the tissue remains, it is a shriveled, carbonized mess.

In Goethe’s ant, the preservation was miraculous. The scans revealed the tentorium, the complex internal skeleton of the head that supports the brain and muscle attachments. They saw the prosternum, a crucial skeletal plate in the thorax. They could trace the insertion points where muscles would have powered the mandibles and legs 40 million years years ago.

"This is the first time," noted Dr. Bernhard Bock of the Phyletic Museum, "that we have been able to visualize the internal endoskeleton of a Cenozoic fossil ant with such clarity." It was a level of detail usually reserved for fresh insects dissected under a microscope, yet this specimen had been sealed in resin since before the first human walked the earth.

Part III: The Creature – Ctenobethylus goepperti

The Identity of the Ghost

The ant was identified as Ctenobethylus goepperti. This species was first described in 1868 by Gustav Mayr, a contemporary of the early amber researchers. It is, ironically, one of the most common ants found in Baltic amber. However, its very commonness had led to scientific neglect. Because there were so many of them, and because they often looked like unremarkable "little black ants," few researchers had bothered to study them in depth. They were the "pigeons" of the Eocene forest—everywhere, and thus ignored.

The Goethe specimen changed that. With the unprecedented resolution of the synchrotron scan, the researchers could perform a taxonomic revision of the entire genus. They discovered that Ctenobethylus possesses a unique combination of features that places it as a "stem lineage" to the modern genus Liometopum.

The "Velvet Tree Ant" Connection

To understand what Ctenobethylus goepperti was like when it was alive, we must look at its living cousins. The genus Liometopum, known today as "velvet tree ants," are aggressive, dominant ants found in North America, Europe, and Asia. They are arboreal, meaning they live almost exclusively in trees. They build massive "carton" nests—structures made of chewed wood and saliva, similar to a wasp's nest—often hidden inside hollow tree trunks.

The anatomical evidence from the Goethe Ant supports this lifestyle. The scans revealed robust mandibular muscles and a head shape suited for heavy lifting and wood chewing. Ctenobethylus was not a soil-dweller scuttling in the dirt; it was a canopy lord. It likely marched in chemically defended trails along the branches of the giant amber-producing pines, tending to herds of aphids and hunting small insects.

The fact that Ctenobethylus is so common in amber (the resin of trees) further confirms its arboreal nature. Soil ants are rarely trapped in tree resin; tree ants, however, live and work in the danger zone. Every step on a sticky pine trunk was a risk. For the Goethe Ant, one misstep 40 million years ago ended its life, but immortalized its form.

Part IV: The Amber Forest

To fully appreciate the significance of this discovery, we must transport ourselves back to the world that Goethe’s ant inhabited: the Eocene Amber Forest.

The Eocene Hothouse

The Eocene epoch (56 to 33.9 million years ago) was a time of "Greenhouse Earth." The planet was significantly warmer than it is today. There were no polar ice caps. Palm trees grew in Alaska, and crocodiles swam in the Arctic Ocean.

Europe was an archipelago of islands bathed in a subtropical climate. The "Baltic" region was not the cold, grey sea of today, but a lush, humid estuary system, perhaps similar to the modern swamps of Florida or the bayous of Louisiana, but populated by a unique mix of flora.

The Hyperdiverse Canopy

The dominant feature of this landscape was the forest. For over a century, scientists debated what kind of tree produced the massive amounts of Baltic amber. It was long called Pinus succinifera—a theoretical pine. Modern chemical analysis and plant inclusions suggest it wasn't just one tree, but a "hyperdiverse" conifer forest.

Imagine a dense woodland composed of relatives of the Golden Larch (Pseudolarix), sequoias, and pines, mixed with broad-leafed angiosperms like oaks and maples. The forest floor was a carpet of ferns and mosses. But the air was thick with the scent of resin.

The trees of this forest were bleeding. Whether due to disease, insect attack, or a specific climatic stress, these ancient conifers produced resin on an industrial scale. This resin dripped down bark, pooled in crevices, and fell to the forest floor, acting as a sticky trap for the ecosystem’s inhabitants.

A Window into a Lost Ecosystem

The Goethe Ant was not alone in its golden tomb. The Jena team’s investigation of the Goethe collection also revealed other inclusions in separate pieces: a fungus gnat (Sciaridae) and a blackfly (Simuliidae).

These three insects—the ant, the gnat, and the fly—allow us to triangulate the environment of the Amber Forest with remarkable precision:

- The Ant (Ctenobethylus): Tells us of the high canopy, the arboreal dominance, and the presence of complex social insect colonies.

- The Fungus Gnat: Tells us of the damp, shaded forest floor where fungi rotted wet wood, providing a breeding ground for these flies.

- The Blackfly: Tells us of moving water. Blackfly larvae require clean, flowing streams to filter-feed. Their presence confirms that the Amber Forest was crisscrossed by rivers and streams, which eventually washed the resin into the marine sediments where it hardened into amber.

Together, they paint a picture of a dynamic, three-dimensional ecosystem: a buzzing, humid forest filled with rushing water, rotting logs, and towering trees, teeming with life that is both alien and strangely familiar.

Part V: The Convergence of Science and Art

The Urphänomen Realized

There is a profound poetic justice in this discovery. Goethe spent his scientific career arguing against the "Newtonian" view of breaking things down into isolated parts. He championed a holistic science, one where the observer and the observed were linked, and where the "whole" was greater than the sum of its parts.

Standard dissection destroys the specimen to understand it. To see the internal muscles of a fossil ant using 19th or 20th-century methods, one would have to crack the amber and grind the fossil into dust, layer by layer. The "whole" would be lost to understand the "part."

Synchrotron tomography is, in a sense, a Goethean technology. It is non-destructive. It preserves the integrity of the specimen—the "phenomenon"—while allowing us to comprehend its inner structure. We can map the muscles without severing them; we can measure the bones without breaking them. The ant remains in the amber, exactly as it was when Goethe held it, yet we now "know" it continuously and thoroughly.

The New Value of Old Things

The discovery of the Goethe Ant has sent a ripple through the museum world. It highlights a concept known as "Digital Curation."

Museums around the world are filled with millions of specimens collected in the 18th and 19th centuries. Many, like Goethe’s amber, are disregarded as "low quality" or "scientifically spent." This discovery proves that these collections are not static graveyards; they are dormant data banks.

"This is just the tip of the iceberg," says Dr. Jörg Hammerschmidt, a co-author of the study. "We have proven that even the most opaque, unpromising stones in historical collections can yield world-class scientific data. We don't always need to go on new expeditions to find new things; sometimes, we just need to look at what we already have with new eyes."

A Message from the Past

In his Maxims and Reflections, Goethe wrote: "The history of the sciences is a great fugue, in which the voices of the nations come one by one into notice."

In 2026, a new voice entered that fugue. It was the voice of a tiny, 40-million-year-old ant, singing across the eons through the medium of X-rays. It spoke of a warm, resin-scented world long before humanity. It spoke of the continuity of life, from the Eocene canopy to the modern laboratory.

But perhaps most poignantly, it spoke of the man who unwittingly saved it. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the poet who sought the eternal in the transient, had achieved a final, unexpected scientific triumph. He had preserved a piece of the Urwelt in his wooden drawer, keeping it safe until the future could invent the light necessary to see it. The stone that was "invisible" to him has now become one of the most visible insects in the history of science—a fitting legacy for the man who demanded, above all else, "More light!"

Reference:

- https://geologie.uni-koeln.de/en/work-groups/palaeontology-and-historical-geology/collections-of-the-institute

- https://designforsustainability.medium.com/the-tip-of-the-iceberg-goethe-s-aphorisms-on-the-theory-of-nature-and-science-ba6e12ebd5f1

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baltic_amber

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ctenobethylus

- https://scitechdaily.com/scientists-discover-40-million-year-old-ant-hidden-in-historic-amber-collection/

- https://arkeonews.net/researchers-discover-a-40-million-year-old-ant-in-amber-once-owned-by-johann-wolfgang-von-goethe/

- https://grokipedia.com/page/40-Million-Year-Old_Ant_in_Goethes_Amber

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/399998470_Discovery_of_Goethe's_amber_ant_its_phylogenetic_and_evolutionary_implications

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12830952/

- https://ediss.uni-goettingen.de/handle/11858/00-1735-0000-0023-3FA3-8

- https://www.schweizerbart.de/papers/palb/detail/304/101278