The vast, sun-drenched silence of the inner solar system is not as empty as it seems. If you could tune your ears to the electromagnetic frequencies of the plasma swirling around the planet Mercury, you would not hear silence. You would hear a song. It is a strange, alien chorus of rising chirps, whistles, and sudden squawks, reminiscent of a flock of birds waking up at dawn in a dense forest. This is the "Hermean Chorus," a symphony of plasma waves known as whistler-mode waves, which play a violent and beautiful role in the invisible environment of the closest planet to the Sun.

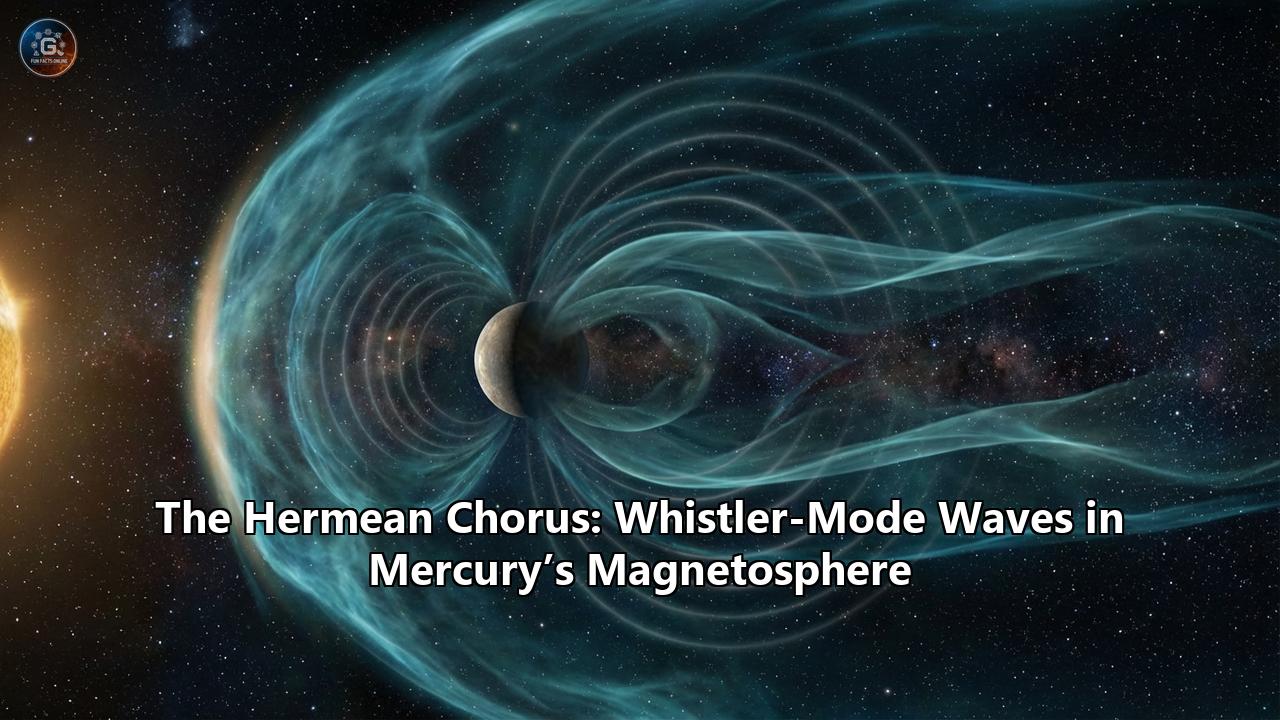

For decades, Mercury was thought to be a geologically dead and magnetically boring world. We knew it had a magnetic field—a surprising discovery by the Mariner 10 spacecraft in the 1970s—but it was considered a weak, miniature version of Earth's, likely incapable of the complex plasma dynamics seen at the gas giants or our own home planet. That view has been shattered. Thanks to the daring flybys of the BepiColombo mission and the legacy of NASA's MESSENGER, we now know that Mercury's magnetosphere is a highly dynamic, intense, and physically bizarre environment where the "music" of plasma waves drives physical processes that don't just happen above the planet, but directly impact its rocky surface.

This is the story of the Hermean Chorus: what it is, how we found it, and why it matters for understanding everything from the formation of auroras to the potential habitability of exoplanets.

Part I: The Discovery of the Hermean Chorus

To understand the magnitude of this discovery, one must appreciate the difficulty of getting to Mercury. It is the elusive trickster of the solar system, racing around the Sun at 47 kilometers per second. To catch it, a spacecraft must shed enormous amounts of orbital energy, a feat that requires years of gravitational assists from Earth, Venus, and Mercury itself.

The first hint of Mercury's magnetic personality came from Mariner 10, but it was just a snapshot. It wasn't until NASA's MESSENGER orbited the planet from 2011 to 2015 that we began to see the complexity of its magnetic environment. MESSENGER observed "bursts" of energetic electrons and hints of plasma instability, but it lacked the specific instrumentation to fully characterize the high-frequency waves that govern these particles.

Enter BepiColombo, a joint mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). Launched in 2018, BepiColombo is actually two spacecraft stacked together: the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (Mio). It is Mio, the spin-stabilized octagonal probe developed by Japan, that is the hero of this story.

Mio was designed with one primary goal: to understand the electromagnetic environment of Mercury. Unlike its predecessors, it carries a state-of-the-art suite of instruments called the Plasma Wave Investigation (PWI). This suite includes search coil magnetometers capable of detecting magnetic fluctuations thousands of times per second—the exact frequency range where "whistler-mode" waves live.

The Dawn of a New SoundDuring its flybys of Mercury in October 2021 and June 2022, while still en route to its final orbit, Mio’s instruments came alive. As the spacecraft swept through the dawn sector of Mercury's magnetosphere—the region where the planet rotates from night into day—the PWI detected distinct, powerful electromagnetic emissions.

These were not random static. On a frequency-time spectrogram (a visual representation of the sound), they appeared as diagonal lines rising in pitch. To plasma physicists, this signature is unmistakable. It is the signature of chorus waves.

On Earth, chorus waves are often called "dawn chorus" because they occur most frequently in the morning sector of the magnetosphere and sound like bird calls when converted to audio. Finding them at Mercury was a triumph. It proved that despite its tiny size and lack of atmosphere, Mercury supports the same fundamental plasma physics as Earth and Jupiter. But as scientists looked closer, they realized the Hermean Chorus had a unique dialect—one shaped by the planet's eccentric magnetic field and its perilous proximity to the Sun.

Part II: The Physics of the Whistle

What exactly is a "whistler-mode wave"? To understand it, we have to zoom in to the microscopic dance of particles within a magnetic field.

A magnetosphere is filled with plasma—a gas of charged particles, primarily electrons and protons, stripped from the Sun and captured by the planet. In the vacuum of space, these particles don't just fly in straight lines. They are slaves to the magnetic field. They spiral around magnetic field lines like beads sliding down a twisted wire.

The Cyclotron ResonanceAs electrons spiral along these field lines, they gyrate at a specific frequency determined by the strength of the magnetic field. This is called the cyclotron frequency. Sometimes, an electromagnetic wave traveling through the plasma will oscillate at a frequency that matches the gyration of these electrons.

When the conditions are just right—specifically, when the wave and the electron are moving in opposite directions but their phases match up—a "cyclotron resonance" occurs. It’s similar to pushing a child on a swing: if you push at the exact right moment in their arc, you transfer energy to them efficiently.

In the case of chorus waves, the energy transfer goes both ways. A population of "unstable" energetic electrons transfers energy to the wave, causing it to grow in amplitude. This amplification happens in a non-linear way, creating a feedback loop. The growing wave creates a "phase bunching" of electrons, which in turn drives the wave even harder. This explosive growth allows the wave frequency to drift rapidly upward, creating the characteristic "chirp" or "whistle" that gives the wave its name.

The Loss Cone InstabilityBut why are the electrons unstable in the first place? The answer lies in the geometry of the magnetic trap.

As electrons bounce back and forth between the planet's magnetic poles, they move into regions of stronger magnetic field. This "magnetic mirror" effect reflects most particles back toward the equator. However, particles that are moving too parallel to the field line will not be reflected. Instead, they dive deep into the polar regions and are lost—crashing into the planet's surface (or atmosphere, in Earth's case).

This creates a "hole" in the electron population known as the loss cone. The distribution of electrons remaining in the magnetosphere becomes "anisotropic"—there are plenty of electrons moving perpendicular to the field lines (trapped), but very few moving parallel (lost). Nature abhors this imbalance. The plasma seeks to return to equilibrium by scattering the trapped electrons into the loss cone. The mechanism it uses to do this is the whistler-mode wave.

The wave grows by "eating" the perpendicular energy of the trapped electrons and scattering their direction of motion. In doing so, it pushes them into the loss cone, sending them raining down onto the planet. This process is the heartbeat of the Hermean Chorus: a continuous cycle of trapped solar wind energy being converted into plasma waves and precipitating particles.

Part III: Mercury’s Asymmetric Heart

While the physics of wave generation is universal, the stage on which it plays out at Mercury is unique. Mercury is not a perfect dipole. Its magnetic equator is shifted northward by about 480 kilometers (roughly 20% of the planet's radius).

This "offset dipole" has profound consequences for the Hermean Chorus.

- The Southern Driver: Because the magnetic center is shifted north, the magnetic field lines in the southern hemisphere are "longer" and have a different curvature compared to the north. The "loss cone" (the angle of escape) is much larger in the south. Paradoxically, a larger loss cone creates a stronger instability. It creates a steeper gradient in the electron distribution, providing more free energy to drive the waves. Simulations and BepiColombo data suggest that the strongest chorus waves are actually generated in the southern hemisphere, driven by this massive anisotropy.

- The Northern Rain: Once these waves are generated, they travel along the magnetic field lines. A wave generated in the south will travel north, and vice versa. As these waves travel, they interact with electrons, scattering them. Because of the offset geometry, the "mirror point" for electrons is different in the north versus the south. The result is a massive asymmetry in where the electrons fall.

- The 2.5x Factor: Recent modeling based on BepiColombo data indicates that while the south drives the waves, the north receives the punishment. The scattering efficiency is such that the precipitation of energetic electrons onto the northern surface is approximately 2.5 times more intense than in the south.

This asymmetry creates a "lopsided" magnetosphere where the dawn sector (where the plasma is injected from the magnetotail) becomes a chaotic engine of wave activity. The "dawn chorus" at Mercury is not just a morning song; it is a localized storm of electromagnetic energy focused by the planet's distorted heart.

Part IV: The Surface Aurora

On Earth, when whistler-mode waves scatter electrons into the atmosphere, they collide with oxygen and nitrogen atoms, exciting them and causing them to glow. We see this as the pulsating aurora—the dancing curtains of green and violet light.

Mercury has no atmosphere to speak of. It has only a tenuous "exosphere" of atoms kicked up from the surface. So, what happens when the Hermean Chorus scatters energetic electrons?

They don't stop. They scream down the magnetic field lines at significant fractions of the speed of light and slam directly into the solid rock of the planet's surface.

X-Ray FluorescenceWhen a high-energy electron hits a rock (specifically, atoms like magnesium, silicon, and calcium in the regolith), it knocks inner-shell electrons out of their orbits. As other electrons fall in to fill these gaps, they release high-energy photons: X-rays.

This phenomenon is known as X-ray fluorescence. It is essentially a "surface aurora." If you had X-ray eyes and looked at Mercury's night side (or the shadowed regions near the terminator), you would see the ground glowing. This glow is not steady; it flickers and pulses in time with the "chirps" of the chorus waves above.

The "electron dewdrop" model, proposed by researchers analyzing BepiColombo data, suggests that distinct packets of chorus waves (the "chirps") cause distinct bundles of electrons to rain down. This creates a patchy, flickering X-ray aurora on the surface.

This direct connection between magnetospheric waves and surface geochemistry is unique to airless, magnetized bodies. It means that the "song" of the magnetosphere is literally etching itself into the surface of the planet. Over geological timescales, this electron bombardment can chemically alter the regolith, potentially creating "space weathering" effects that are distinct from those on the Moon, where there is no global magnetic field to focus the particles.

Part V: Hiss, Chirps, and the Missing Plasmasphere

A subtle but important distinction in the study of planetary radio emissions is the difference between "chorus" and "hiss."

On Earth, we have a "plasmasphere"—a dense, donut-shaped cloud of cold plasma that rotates with the Earth. Inside this high-density region, whistler-mode waves evolve into a structureless, incoherent static known as plasmaspheric hiss. It sounds like white noise or the hiss of a simplified radio. This hiss is crucial for maintaining the "slot region" between Earth's Van Allen radiation belts, as it slowly scrubs energetic electrons out of existence.

Mercury, however, is too small and rotates too slowly to hold onto a dense, co-rotating plasmasphere. The solar wind strips plasma away too quickly.

The "Naked" ChorusBecause Mercury lacks a dense plasmasphere, the "hiss" phenomenon as we know it on Earth is largely absent or physically different. The waves observed by BepiColombo are predominantly the discrete, structured chorus type. They are "naked" waves, propagating through the tenuous plasma without being trapped and scattered into a hiss-like haze by a dense cold plasma torus.

However, the search results hint at complexity. "Narrowband whistler waves" have been observed near reconnection regions in the magnetotail. These are distinct from the chirping chorus. They are steady, localized tones, humming at around half the electron cyclotron frequency. These waves are the "drones" accompanying the chirping chorus, generated by the violent snapping of magnetic field lines on the planet's night side.

Part VI: Comparative Planetology – The Universal Song

The discovery of Hermean chorus waves allows scientists to perform a grand experiment in "comparative planetology." We can now compare the same phenomenon across three vastly different scales:

- Mercury: A tiny, airless rock with a weak magnetic field (1% of Earth's), located deep in the Sun's gravity well.

- Earth: A medium-sized planet with a strong field, a dense atmosphere, and a stable plasmasphere.

- Jupiter/Saturn: Gas giants with colossal magnetic fields, rapid rotation, and plasma sources from volcanic moons (Io and Enceladus).

Remarkably, the physics holds up. The frequency of the chorus waves scales perfectly with the strength of the magnetic field.

- At Jupiter: The magnetic field is immense, so the electron cyclotron frequency is high. Chorus waves there can be heard in the audible range but extend into much higher frequencies.

- At Earth: Chorus waves typically sing between 0.5 kHz and 10 kHz—perfectly within the range of human hearing if converted directly to sound.

- At Mercury: Because the magnetic field is weak (only about 300 nanotesla near the equator compared to Earth's 30,000), the cyclotron frequency is much lower. The "whistles" of Mercury are deep, low-frequency groans compared to Earth's soprano chirps. However, relative to the local environment, they play the exact same tune.

Perhaps the closest cousin to Mercury is not a planet, but a moon. Ganymede, Jupiter's largest moon, is the only other rocky body in the solar system with its own intrinsic magnetosphere. Galileo spacecraft data showed "million-fold" increases in wave power near Ganymede. Both Mercury and Ganymede are "mini-magnetospheres" embedded in a flowing plasma (solar wind for Mercury, Jupiter's magnetosphere for Ganymede). Studying the Hermean Chorus helps us understand Ganymede, and by extension, the potential habitability of icy moons orbiting gas giants in other star systems. If strong whistler waves are accelerating electrons into Ganymede's icy surface, they could be driving radiolytic chemistry—creating oxygen and oxidants that might seep into a subsurface ocean. The same physics observed at Mercury could be a key to life elsewhere.

Part VII: Listening to the Void

How do we "hear" these waves? The PWI instrument on BepiColombo/Mio uses a search coil magnetometer (SCM). This is essentially a coil of copper wire wrapped around a high-permeability core. When a magnetic wave passes through the coil, it induces a tiny electric current.

The SCM on Mio is incredibly sensitive. It can detect magnetic fluctuations as small as a few femtotesla (a quadrillionth of a tesla). It covers a frequency range from 0.1 Hz up to 20 kHz (Low Frequency) and up to 640 kHz (High Frequency).

SonificationSince these are electromagnetic waves, not sound waves (sound cannot travel in a vacuum), we cannot hear them directly. But because they occur in the "audio frequency" range (20 Hz to 20,000 Hz), we can simply feed the signal from the magnetometer into a speaker.

If you were to listen to the raw data from Mio during a dawn-sector flyby, you would hear:

- The Background: A low rumble or crackle, representing the turbulent solar wind.

- The Chorus: Distinct, rising "pyew-pyew" sounds, similar to laser blasts in 1970s sci-fi movies, or the chirping of frogs.

- The Cadence: The chirps often come in bursts, clustered together in time. This is the "sub-packet" structure, revealing the non-linear "gulping" of energy by the waves.

This "sonification" is not just for public outreach. It is a diagnostic tool. The human ear is incredibly good at detecting patterns in noisy data. By listening to the plasma, physicists can distinguish between chorus (chirps), hiss (static), and other phenomena like "lion roars" (a specific type of wave found in magnetosheaths).

Part VIII: The Future – Orbital Resonance

We are currently in the "teaser trailer" phase of Mercury exploration. BepiColombo has only performed flybys—brief, high-speed encounters that give us a slice of data.

In late 2025/early 2026, the spacecraft will fire its ion thrusters and enter orbit. The two probes will separate. MPO will go into a low orbit to map the surface, while Mio will take a highly elliptical orbit (up to 11,000 km altitude) to dive deep into the heart of the magnetosphere.

What are we waiting for?- Global Mapping: We have only heard the chorus at dawn. Does it happen at dusk? What about the night side? Mio will provide a 4D map (space + time) of the waves.

- The Feedback Loop: We want to see the "smoking gun": simultaneous measurements of the waves and the precipitating electrons, followed by a detection of the X-ray flare from the surface below (using MPO's X-ray spectrometer, MIXS). Catching this entire chain of events in real-time is the "holy grail" of the mission.

- Space Weathering: By quantifying exactly how much energy these waves dump into the surface, planetary scientists can calculate how quickly Mercury's rocks are being altered. This could explain the mysterious "hollows" and the dark, carbon-rich material that coats the planet.

Conclusion: The Singing Planet

The image of Mercury has been transformed. It is no longer just a cratered, sun-baked rock. It is a world wrapped in a dynamic, invisible cloak of energy. It is a world where magnetic fields snap and reconnect, launching beams of particles that scream toward the surface. It is a world where the dawn brings not just the blinding light of the Sun, but a chorus of electromagnetic song that resonates through the vacuum.

The "Hermean Chorus" is a reminder that the universe is alive with activity, even in the most inhospitable places. It teaches us that the laws of physics are robust—scaling from the giant magnetosphere of Jupiter down to the tiny, struggling field of Mercury. As BepiColombo prepares to enter orbit, we are tuning our radios to 88 MHz (Mercury Hertz), ready to listen to the full symphony of the innermost planet.

The song of Mercury is playing. We are finally learning the lyrics.

Reference:

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/223420668_The_Plasma_Wave_Investigation_PWI_onboard_the_BepiColomboMMO_First_measurement_of_electric_fields_electromagnetic_waves_and_radio_waves_around_Mercury

- https://rbm.epss.ucla.edu/strong-whistler-mode-waves-observed-in-the-vicinity-of-jupiters-moons/

- https://miosc.isee.nagoya-u.ac.jp/about/satellite/pwi_sc.php

- https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/bepicolombo/pwi

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sZxxeb0BUFA

- https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/BepiColombo/From_Messenger_to_BepiColombo