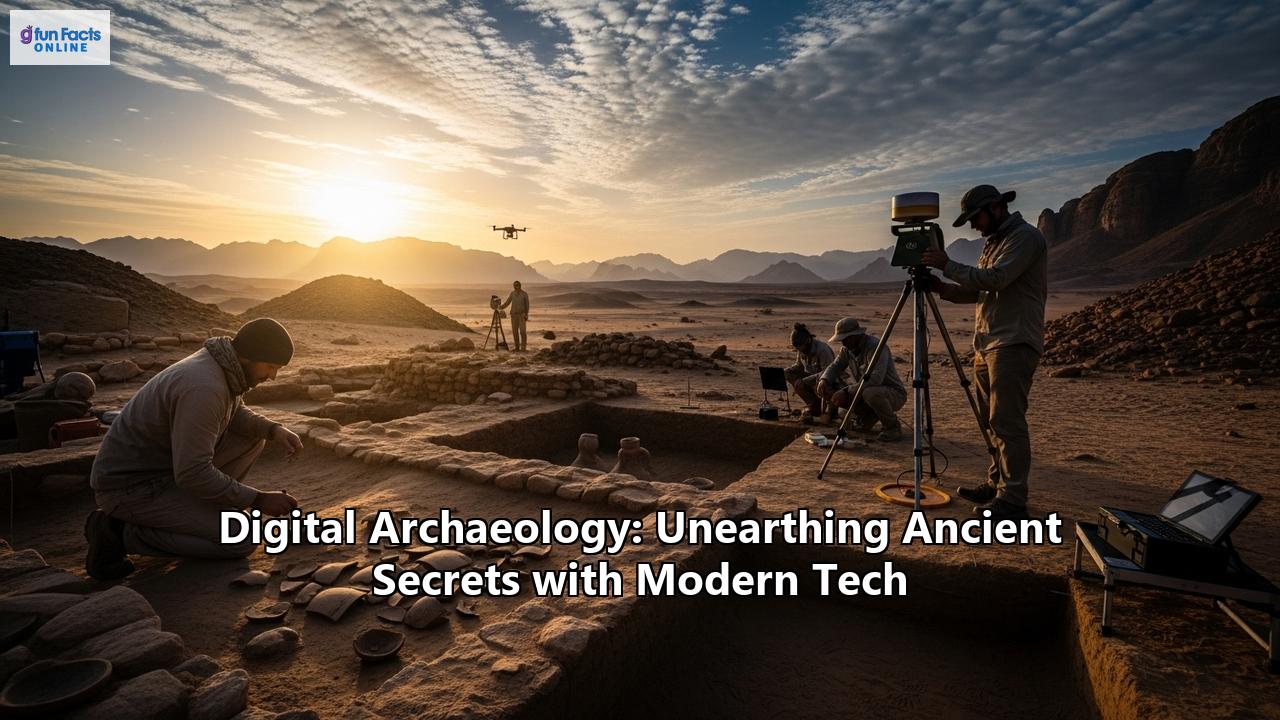

Digital Archaeology: Unearthing Ancient Secrets with Modern Tech

In the dense, often impenetrable jungles of Mesoamerica, a lost world has re-emerged. Not through the painstaking slash of a machete, but through the silent pulse of a laser. This is the new face of archaeology, a discipline once solely defined by the trowel and the trench, now increasingly shaped by the powerful lens of modern technology. From the heavens, satellites peer through the sands of time in Egypt, revealing settlements lost for millennia. Beneath the earth, ground-penetrating radar maps the spectral outlines of Viking ship burials without disturbing a single grain of soil. This is digital archaeology, a revolutionary field that is peeling back the layers of history in ways previously unimaginable, transforming our understanding of the human story.

The integration of digital tools and techniques with traditional archaeological methods is not merely an upgrade of the archaeologist's toolkit; it represents a fundamental shift in how we discover, analyze, and interpret the past. It is a field that encompasses a vast array of technologies, from the satellite imagery that offers a god's-eye view of ancient landscapes, to the microscopic analysis of artifacts guided by artificial intelligence. This technological leap allows for non-invasive exploration, preserving fragile sites while yielding data of unprecedented accuracy and scale. It empowers archaeologists to reconstruct ancient worlds in stunning three-dimensional detail, to walk through virtual Roman villas, and to share these immersive experiences with a global audience. But beyond the gee-whiz factor of these innovations lies a deeper, more profound impact. Digital archaeology is democratizing the past, making it more accessible, more collaborative, and more engaging than ever before. It is also forcing the discipline to confront new challenges, from the ethical dilemmas of data ownership to the pressing need to preserve our digital heritage for future generations. This is the story of digital archaeology, a journey into how the ones and zeros of the digital age are unlocking the secrets of our ancient ancestors.

From the Stars to the Soil: A Universe of Non-Invasive Technologies

The classic image of archaeology is one of painstaking excavation, a slow and often destructive process of revealing the past. While excavation remains a cornerstone of the discipline, a new suite of non-invasive technologies is allowing archaeologists to see beneath the surface of the earth without ever breaking ground. These tools, which range from satellite-borne sensors to ground-based geophysical instruments, are revolutionizing the process of site discovery and survey, saving time, money, and preserving archaeological contexts for future generations.

A God's-Eye View: Satellite and Aerial Imagery

Long before the first trench is dug, the search for ancient sites often begins from the air. For decades, archaeologists have used aerial photography to spot the subtle tell-tale signs of buried remains, such as crop marks, soil marks, and shadow marks. But the advent of high-resolution satellite imagery has taken this approach to a whole new level. Satellites equipped with powerful cameras and multispectral sensors can survey vast and remote areas, revealing features invisible to the naked eye.

One of the most prominent figures in this field is Dr. Sarah Parcak, a "space archaeologist" who has used satellite imagery to uncover thousands of previously unknown sites in Egypt and across the Roman Empire. Her work demonstrates the power of different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum to reveal the past. For instance, infrared imagery can highlight subtle variations in vegetation growth, as plants growing over buried stone walls will be less healthy than those in deeper soil. This creates "crop marks" that can delineate the outlines of entire buildings, or even entire cities. By processing satellite data, Parcak and her team have been able to identify more than 3,000 ancient settlements, over a dozen lost pyramids, and more than a thousand forgotten tombs in Egypt alone. Her work has also been instrumental in monitoring the looting of archaeological sites, providing crucial data for heritage protection efforts.

The use of satellite imagery is not limited to the deserts of Egypt. In the dense jungles of the Amazon, and the vast plains of Central Asia, this technology is helping to map ancient landscapes and understand human-environment interactions on a grand scale. Publicly available platforms like Google Earth have also become invaluable tools for archaeologists, allowing for the systematic survey of huge areas and the identification of potential sites from the comfort of a lab.

Piercing the Veil: The Power of LiDAR

Perhaps no technology has had a more dramatic impact on archaeological discovery in recent years than LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging). This remote sensing technique works by firing millions of laser pulses from an aircraft or drone towards the ground and measuring the time it takes for the light to reflect back. The result is a highly detailed, three-dimensional map of the terrain. Crucially for archaeology, LiDAR can "see" through vegetation, allowing researchers to digitally remove the tree canopy and reveal the ground surface below with astonishing clarity.

The impact of LiDAR has been particularly transformative in the study of the ancient Maya civilization, whose cities were swallowed by the dense jungles of Mesoamerica. For decades, archaeologists had to rely on arduous ground surveys, hacking through the undergrowth to map the ruins. Now, with a single flyover, LiDAR can reveal the full extent of ancient cities, including not just the monumental temples and palaces, but also the houses of ordinary people, agricultural terraces, and vast networks of causeways that connected them.

A landmark 2018 study in the Petén region of Guatemala used LiDAR to survey over 2,100 square kilometers of forest, revealing more than 61,000 previously unknown structures. This "Maya Megalopolis" demonstrated that the Maya population was far larger and more urbanized than previously thought, with an estimated 11 million people living in the region during the Classic period. The LiDAR data also revealed extensive defensive fortifications, challenging the long-held view of the Maya as a largely peaceful civilization.

More recently, in 2020, LiDAR was instrumental in the discovery of Aguada Fénix in Mexico, the oldest and largest known ceremonial structure in the Maya world, a massive earthen platform dating back to 1000 BCE. These discoveries are not just adding new dots to the map; they are fundamentally rewriting our understanding of Maya society, its scale, its complexity, and its history.

Peering Beneath the Earth: Ground-Penetrating Radar and Magnetometry

Once a potential site has been identified from the air, the next step is often to get a closer look at what lies beneath the surface. Geophysical survey methods allow archaeologists to do just that, creating images of the subsurface without the need for excavation.

Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) is one of the most powerful of these techniques. It works by sending electromagnetic pulses into the ground and recording the reflections that bounce back from buried objects and features. The resulting data can be used to create 3D maps of the subsurface, revealing the outlines of walls, ditches, burials, and other archaeological remains.

A prime example of the power of GPR comes from the famous Anglo-Saxon burial site of Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, England. In recent investigations, GPR has been used to survey the Royal Burial Ground, an area containing a number of burial mounds, including the one that housed the spectacular ship burial discovered in 1939. The GPR surveys have provided a much more complete picture of the site, revealing details about the construction of the burial mounds and identifying new features for future investigation. This non-invasive approach is crucial for a site as significant and fragile as Sutton Hoo, allowing for a deeper understanding of its history while preserving it for the future.

Magnetometry is another widely used geophysical technique. It measures minute variations in the Earth's magnetic field, which can be caused by buried archaeological features. For example, a fired clay hearth will have a different magnetic signature than the surrounding soil. By systematically surveying an area with a magnetometer, archaeologists can create a detailed map of these magnetic anomalies, which can then be interpreted to identify potential archaeological features. At Sutton Hoo, magnetometry has been used in conjunction with GPR to survey areas adjacent to the known burial ground, with the aim of discovering further evidence of Anglo-Saxon activity.

Together, these non-invasive technologies have become an indispensable part of the archaeological toolkit. They allow for the rapid and efficient survey of large areas, the precise targeting of excavations, and the preservation of archaeological sites for future generations. They are, in essence, giving archaeologists a new set of eyes with which to explore the past.

Reconstructing Lost Worlds: The Magic of 3D Modeling and Virtual Reality

While non-invasive survey techniques are transforming how we find and map ancient sites, another set of digital tools is revolutionizing how we visualize and understand them. 3D modeling, photogrammetry, and virtual reality are allowing archaeologists to reconstruct ancient structures, artifacts, and even entire cities with breathtaking detail, offering new avenues for research and public engagement.

Building the Past in Three Dimensions: 3D Modeling

3D modeling is the process of creating a three-dimensional digital representation of an object or surface. In archaeology, this can be applied to anything from a tiny potsherd to a vast cityscape. These models are not just pretty pictures; they are powerful analytical tools that can be measured, manipulated, and studied in ways that are impossible with physical objects or two-dimensional drawings.

One of the most spectacular examples of the use of 3D modeling in archaeology comes from the ruins of Pompeii, the Roman city famously preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. The Swedish Pompeii Project, for example, has used a combination of laser scanning and drone imagery to create a highly detailed 3D model of an entire city block, the Insula V 1. This model allows researchers to explore the houses, shops, and gardens of this neighborhood as they were at the moment of the eruption, providing new insights into daily life in the Roman world. In a similar vein, researchers from Lund University have created a stunning 3D reconstruction of the house of the banker Caecilius Iucundus, bringing to life the opulent world of a wealthy Pompeian family.

These models are created by integrating a vast amount of data, including the results of new excavations, old excavation records, photographs of lost frescoes, and 19th-century drawings of the site. The result is a dynamic and evolving representation of the past, one that can be updated as new information comes to light. The digital twin of the Pompeii I.14 excavation project, for example, allows researchers to revisit the site virtually and continue their analysis long after the physical excavation has ended.

From Photos to 3D: The Art of Photogrammetry

While laser scanning is a powerful tool for creating 3D models, it can be expensive and require specialized equipment. Photogrammetry offers a more accessible alternative. This technique involves taking hundreds or even thousands of overlapping photographs of an object or site from different angles and then using specialized software to "stitch" them together into a 3D model.

Photogrammetry has proven to be particularly valuable in the challenging environment of underwater archaeology. Documenting submerged sites is a race against time, as they are constantly threatened by erosion, currents, and human activity. Photogrammetry allows for the rapid and accurate recording of underwater sites, creating a permanent digital record that can be studied in detail back in the lab. The resulting 3D models can reveal features that were missed during the initial dives and can be used to plan future excavations. To achieve the best results, divers must be trained in specific photographic techniques, and the use of remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) is becoming increasingly common for data collection.

Stepping into History: Virtual and Augmented Reality

Perhaps the most exciting application of 3D modeling is in the creation of immersive virtual and augmented reality experiences. Virtual Reality (VR) allows users to step into a completely digital environment, while Augmented Reality (AR) overlays digital information onto the real world. Both technologies are transforming how we experience and learn about the past.

In Athens, for example, a company called Lithodomos VR has created a stunningly detailed virtual reconstruction of the ancient city as it was 2,000 years ago. Users can don a VR headset and walk through the Agora, climb the Acropolis, and marvel at the Parthenon in all its original glory. The creators have placed a strong emphasis on archaeological accuracy, ensuring that the experience is not just entertaining, but also educational. Another app, "Chronos," uses augmented reality to allow visitors to the Acropolis to see how the monuments looked in antiquity through their smartphones.

These immersive experiences are not just for the public. Archaeologists themselves are using VR to explore their data in new ways. By "walking through" a 3D model of an excavation, researchers can gain a better understanding of the spatial relationships between different features and artifacts. VR is also being used to train the next generation of archaeologists, providing them with a safe and controlled environment in which to learn excavation techniques.

From the meticulous reconstruction of a single artifact to the creation of entire virtual cities, 3D modeling and its related technologies are bringing the past to life in ways that were once the stuff of science fiction. They are not only transforming archaeological research, but also making the ancient world more accessible and engaging for everyone.

The Digital Scribe: Data Analysis, AI, and Deciphering the Past

The digital revolution in archaeology is not just about creating stunning visualizations; it's also about extracting new meaning from the vast amounts of data that are now being collected. Geographic Information Systems (GIS), artificial intelligence (AI), and advanced data analysis techniques are providing archaeologists with powerful new tools to analyze their findings and ask new questions about the past.

Mapping the Past with GIS

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are computer-based tools for capturing, storing, analyzing, and managing geographically referenced data. In archaeology, GIS has become an indispensable tool for a wide range of applications, from mapping the distribution of artifacts at a single site to analyzing trade routes that spanned entire continents.

One powerful example of the use of GIS in archaeology is the study of ancient Roman trade routes. The Roman Empire was a vast and complex economic system, and understanding how goods and materials moved across it is crucial for understanding its social and political structure. By combining a wide range of data within a GIS, including the locations of known Roman roads, navigable rivers, archaeological sites, and the distribution of artifacts such as amphorae (used to transport goods like olive oil and wine), archaeologists can model and analyze the Roman transport network.

This allows them to go beyond simply mapping the routes and to start asking more complex questions. For example, they can use GIS to calculate the "cost" of travel between different points, taking into account factors like terrain, distance, and the availability of different modes of transport. This can help to explain why certain cities grew and prospered while others did not. By analyzing the distribution of different types of goods, archaeologists can also reconstruct the flow of trade and identify the major economic hubs of the empire.

The Rise of the Machines: Artificial Intelligence in Archaeology

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are poised to have a transformative impact on archaeology. These technologies excel at identifying patterns in large datasets, a task that is often time-consuming and difficult for human researchers.

One area where AI is already making a significant contribution is in the classification of artifacts, particularly pottery. Pottery is one of the most common finds on archaeological sites, and its style and form can provide valuable information about the date of a site and its connections to other cultures. However, the process of sorting and classifying thousands of pottery sherds by hand is incredibly laborious.

Researchers at Northern Arizona University have successfully trained a form of AI known as a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to classify different types of prehistoric Southwestern pottery with an accuracy that rivals, and in some cases exceeds, that of human experts. The AI can rapidly sort through thousands of images of sherds, identifying the stylistic categories to which they belong. Not only does this save a huge amount of time, but it also provides a more consistent and objective classification than can be achieved by human sorters, who can be influenced by fatigue or personal biases.

AI is also being used to help reconstruct fragmented artifacts and even to decipher ancient languages. By training a neural network on a database of complete artifacts, for example, it is possible for the AI to predict the missing parts of a broken pot. In the field of epigraphy, machine learning algorithms are being used to help piece together fragmented inscriptions and even to suggest possible readings for damaged or unknown words.

Deciphering the Code: Data Analysis and Ancient Texts

The application of digital tools extends to the study of ancient texts. The vast corpus of cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia, for example, represents a treasure trove of information about the world's first civilizations. However, these texts are often fragmentary and written in a complex script that is difficult to decipher.

Digital technologies are helping to overcome these challenges in a number of ways. High-resolution 3D scanning of the tablets allows for the creation of detailed digital models that can be rotated and examined in ways that are not possible with the physical objects. This can help to reveal details of the script that are not visible to the naked eye.

Furthermore, the application of data analysis and machine learning techniques to the digitized texts is opening up new avenues of research. By analyzing the statistical patterns in the language, it is possible to identify different scribal hands, to reconstruct the chronological development of the script, and even to identify different dialects and literary genres. AI is also being used to help with the translation of cuneiform texts, by comparing them to a large database of known words and phrases.

From the spatial analysis of ancient landscapes to the automated classification of artifacts and the deciphering of long-lost languages, the digital tools of data analysis are providing archaeologists with a new and powerful lens through which to view the past.

The Future is Now: Drones, Robots, and the Next Frontier

As technology continues to advance at a breakneck pace, the field of digital archaeology is constantly evolving. The tools and techniques that are cutting-edge today will be commonplace tomorrow, and a new generation of technologies is already on the horizon, promising to further revolutionize how we explore and understand the past.

The Archaeologist's New Best Friend: Drones and Robots

Drones, or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), are rapidly becoming one of the most versatile and valuable tools in the archaeologist's toolkit. Cheaper and more flexible than traditional aircraft, drones can be equipped with a variety of sensors, including high-resolution cameras, LiDAR scanners, and multispectral imagers. They are ideal for a wide range of tasks, from the initial survey of a site to the detailed mapping of an excavation in progress.

One of the key advantages of drones is their ability to access remote and hazardous locations. Whether it's a mountaintop fortress or a site in a dense, inaccessible jungle, a drone can be deployed quickly and safely to collect data. The high-resolution 3D models and orthophotos generated from drone surveys provide a detailed and accurate record of a site, which can be used for analysis, interpretation, and preservation.

Looking to the future, the role of robotics in archaeology is set to expand dramatically. "Robotic archaeologists" are being developed that can operate in environments that are too dangerous or difficult for humans, such as deep-sea shipwrecks or unstable underground tombs. These robots can be equipped with a range of sensors and tools, allowing them to not only survey a site but also to carry out delicate excavation and recovery tasks. It is predicted that by 2030, robots will conduct more than 50% of excavations in challenging terrains.

The integration of AI with drones and robots will further enhance their capabilities. Imagine a fleet of autonomous drones that can survey a vast landscape, identify potential archaeological sites using machine learning algorithms, and then deploy ground-based robots to carry out a preliminary investigation. This is the future of archaeological fieldwork.

Miniaturization and New Sensors: Seeing the Invisible

Another key trend that will shape the future of digital archaeology is the miniaturization of sensors and the development of new sensing technologies. Ground-penetrating radar and hyperspectral cameras, for example, are now being made small enough to be mounted on drones. This will allow for the collection of a much wider range of data from the air, including information about the subsurface and the chemical composition of the soil.

New types of sensors are also being developed that will allow archaeologists to "see" the past in new ways. For example, advances in chemical analysis are making it possible to detect the faint traces of organic materials that have long since decayed, providing new insights into ancient diet, medicine, and ritual practices.

The Digital Twin and the Metaverse: Immersive Pasts

The concept of the "digital twin" – a virtual recreation of a physical object or system that is updated with real-time data – is gaining traction in archaeology. An excavation, for example, can be documented in such detail that a perfect digital replica is created. This digital twin can then be used for analysis, interpretation, and education, and it can be preserved as a permanent record of the site long after the physical excavation is complete.

In the future, it is not hard to imagine these digital twins being integrated into the "metaverse," a persistent, shared virtual space where users can interact with each other and with digital objects. Imagine being able to walk through a completely immersive and interactive reconstruction of ancient Rome, to chat with a virtual Julius Caesar, or to take part in a simulated archaeological dig. This is the ultimate promise of digital archaeology: not just to study the past, but to experience it.

The Double-Edged Sword: Challenges and Ethical Considerations

For all its transformative potential, the rise of digital archaeology is not without its challenges and ethical dilemmas. The very technologies that are opening up new frontiers of discovery are also raising new questions about data ownership, access, preservation, and the very nature of the archaeological record.

The Digital Deluge and the Preservation Crisis

The digital tools used in archaeology today are generating a "data deluge," a torrent of information on an unprecedented scale. While this data is incredibly valuable, it is also incredibly fragile. Digital files can be corrupted, storage media can become obsolete, and software can become unreadable in a matter of years. This has led to what some have called a "digital curation crisis," a very real fear that we are creating a "digital dark age" for future generations of archaeologists.

Unlike physical artifacts, which can survive for millennia, digital data requires constant management and migration to new formats to ensure its long-term survival. This is a costly and time-consuming process that many archaeological projects and institutions are ill-equipped to handle. The result is that vast amounts of valuable digital data are at risk of being lost forever.

Who Owns the Past? Data Ownership and Access

The question of who owns archaeological data is a complex and contentious one. Does it belong to the archaeologist who collected it, the institution that funded the research, or the country where the site is located? In an age of digital data that can be easily copied and shared across the globe, these questions have become even more pressing.

Many digital preservation repositories champion the "democratization" of academic data, advocating for open access to all. However, this can conflict with the legal and ethical obligations of archaeologists, particularly when dealing with sensitive information, such as the location of unexcavated sites (which could be a target for looters) or the remains of indigenous peoples. Striking a balance between open access and the protection of sensitive data is one of the key ethical challenges facing digital archaeology today.

The Need for New Skills and Standards

The shift to digital methods in archaeology requires a new set of skills and expertise. Archaeologists now need to be proficient in everything from GIS and 3D modeling to database management and data analysis. This has significant implications for archaeological training and education. Universities and other training institutions need to adapt their curricula to ensure that the next generation of archaeologists has the digital literacy skills they need to succeed.

There is also a pressing need for the development of clear standards and best practices for the creation, management, and preservation of digital archaeological data. Without such standards, there is a risk that data will be collected in a haphazard and inconsistent manner, making it difficult to compare and integrate data from different projects.

The Allure of the Virtual and the Importance of the Real

Finally, there is a more philosophical challenge that comes with the rise of digital archaeology. As our digital reconstructions of the past become more and more realistic and immersive, there is a danger that we will lose sight of the real thing. The virtual past, no matter how detailed, is still a representation, an interpretation. It is not the past itself.

It is crucial that we do not let the allure of the virtual distract us from the importance of preserving the physical remains of the past. The trowel and the trench are not obsolete. Excavation will always be a vital part of archaeology, providing the raw data upon which our digital reconstructions are built. The future of archaeology lies not in a choice between the digital and the real, but in a creative and critical integration of the two.

In conclusion, digital archaeology is a field in flux, a dynamic and exciting area of research that is transforming our understanding of the human story. The tools and techniques of the digital age are allowing us to see the past with new eyes, to uncover lost cities, to reconstruct ancient worlds, and to ask new and profound questions about our shared heritage. But with this great power comes great responsibility. The challenges of data preservation, ownership, and ethics are real and pressing. As we continue to push the boundaries of what is possible with digital technology, we must do so with a critical and self-aware perspective, ensuring that we are not only unearthing the secrets of the past, but also preserving them for the future. The digital age has given us a new set of tools to explore the past, but the fundamental mission of archaeology remains the same: to understand what it means to be human.

Reference:

- https://www.google.com/search?q=time+in+Naples,+IT

- https://www.google.com/search?q=time+in+%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B8%D9%87%D9%8A%D8%B1+%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B5%D8%AD%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%88%D9%89+%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%89+%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%AF,+EG

- https://milstein-program.as.cornell.edu/3d-modeling-ancient-gardens-pompeii

- https://scitechdaily.com/archaeologists-pioneer-new-technology-to-sort-ancient-pottery/

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/space-archaeologist-sarah-parcak-winner-smithsonians-history-ingenuity-award-180961120/

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/abs/satellite-imagery-and-heritage-damage-in-egypt-a-response-to-parcak-et-al-2016/322A107102620A62A8CD68331FEDB07C

- https://static.nationaltrust.org.uk/waf/waf.html?_event_transid=fdf6856c6b7cdc4875053cb6f56905a2ba847ac235bc467cabe4b707f01bfa2e

- https://www.flyingglass.com.au/why-is-drone-technology-useful-for-archaeologists/

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/advances-in-archaeological-practice/article/abs/use-of-lidar-in-understanding-the-ancient-maya-landscape/2D44395C82A2503534071CEE3568C5B7

- https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/blog/lidar-images-reveal-mayan-civilization

- https://amazingtemples.com/en/amazing-temples-english/science-discoveries-en/unlocking-the-secrets-of-mayan-archaeology-the-role-of-lidar-technology/

- https://www.consandheritage.co.uk/articles/national-trust-begins-research-project-with-time-team-in-the-hope-of-shedding-new-light-on-sutton-hoo

- https://the-past.com/news/time-team-investigate-sutton-hoo/

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2016/10/07/friday-digital-archaeology-digest-3d-modeling-digital-pompeii-and-libyan-heritage/

- https://www.livescience.com/56419-ancient-pompeii-home-reconstructed-in-3d.html

- https://www.pompejiprojektet.se/insula-v-1/documentation-of-insula-v-1/3d-models-3d-gis/

- https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/blog/modeling-pompeii-collaboartive-archaeology

- https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/technology/photogrammetry/photogrammetry.html

- https://isprs-archives.copernicus.org/articles/XLII-2-W10/85/2019/

- https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1312/12/3/413

- https://www.vi-mm.eu/2017/10/16/experience-ancient-athens-in-vr/

- https://ancientathens3d.com/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ulAxMLJ7O7M

- https://apnews.com/article/acropolis-greece-virtual-restoration-augmented-reality-273f4a1c64c6aa72a1c3c3d39e34d252

- https://publikationen.uni-tuebingen.de/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10900/61367/46_Isaksen_CAA_2005.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/94433/1/The%20seeds%20of%20commerce.%20A%20network%20analysis-based%20approach%20to%20the%20Romano-British%20transport%20system_post-print.pdf

- https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/94433/

- https://www.maajournal.com/index.php/maa/article/view/1518

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321360502_A_GIS-based_analysis_of_the_rationale_behind_Roman_roads_The_case_of_the_so-called_via_XVII_NW_Iberian_Peninsula

- https://dev.to/ray_parker01/archaeology-meets-artificial-intelligence-a-new-era-of-exploration-125k

- https://www.mdpi.com/2571-9408/4/1/8

- https://www.ultralytics.com/blog/ai-in-archaeology-paves-the-way-for-new-discoveries

- https://autogpt.net/the-role-of-ai-in-modern-archaeology/

- https://3laws.io/pages/Drones_and_the_Future_of_Robotic_archaeologists.html

- https://3laws.io/pages/UAVs_and_the_Future_of_Robotic_archaeologists.html

- https://www.luciongroup.com/news/drones-heritage-the-rise-of-drone-technology-in-archaeology/

- https://coptrz.com/blog/the-rise-of-drone-technology-in-archaeology/

- https://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue58/22/full-text.html

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280775386_The_Digital_Dilemma_Preservation_and_the_Digital_Archaeological_Record

- https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/app/uploads/2022/05/british_library.pdf

- https://www.studysmarter.co.uk/explanations/archaeology/conservation-and-preservation/digital-preservation-archaeology/

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/advances-in-archaeological-practice/article/survey-of-how-archaeological-repositories-are-managing-digital-associated-records-and-data/952A6A3DB114930704D237F266D92C7A