Part I: The Invisible Crisis Rising from the Depths

The ocean view from the rugged cliffs of the Pacific Northwest or the arid coastlines of northern Chile is one of deceptive abundance. Seabirds wheel overhead, diving into churning, foam-flecked waters. Fishing boats bob on the horizon, hauling in nets heavy with sardines, anchovies, or crab. To the casual observer, these cold, turbulent waters are the picture of vitality—the engines of the marine world.

And they are. These regions are the world’s great upwelling systems, where deep, nutrient-rich water rises from the abyss to bathe the sunlit surface. They cover less than 3% of the ocean’s surface yet support over 20% of the global fish catch. They are the ocean’s breadbaskets.

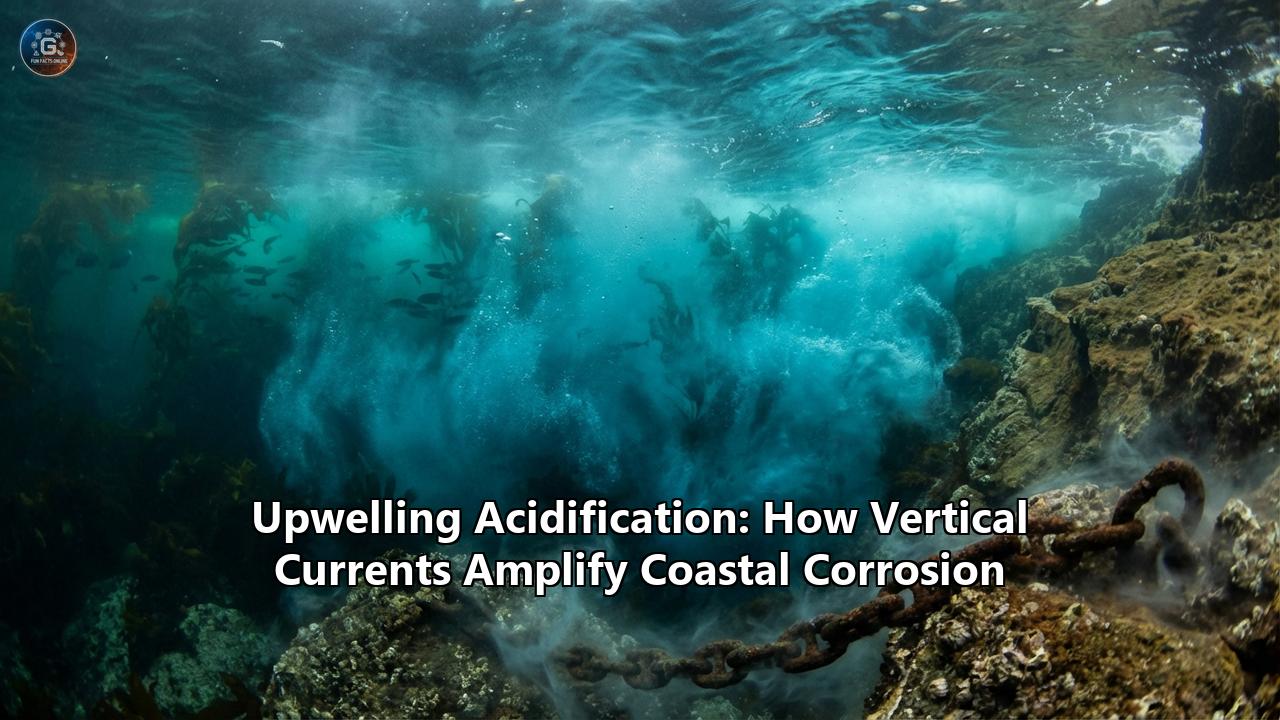

But hidden within this vertical conveyor belt is a chemical assassin. The same currents that bring the nutrients to feed the plankton bloom are also carrying a toxic payload: ancient, corrosive water that is rapidly turning these cradles of life into graveyards.

This is the phenomenon of Upwelling Acidification. It is a localized but potent amplification of the global ocean acidification crisis. While the open ocean slowly sours due to the absorption of human-made carbon dioxide, coastal upwelling zones are being hit by a "double whammy"—a collision of anthropogenic pollution from above and naturally acidified water from below. The result is a corrosive soup that dissolves shells, warps the behavior of fish, and threatens to crumble the very foundations of the coastal economy.

This is not a future projection. It is happening now. From the dissolving larvae of oysters in Oregon hatcheries to the pitting of concrete pilings in industrial harbors, the ocean is beginning to consume the life and structures that border it. This article explores the physics, chemistry, biology, and economics of this rising tide, unraveling how vertical currents are amplifying the greatest chemical change our oceans have seen in 50 million years.

Part II: Oceanography 101 – The Engine of Upwelling

To understand why these specific coastlines are under siege, we must first understand the engine that drives them. Upwelling is not a random occurrence; it is a precise physical process governed by the rotation of the Earth and the blowing of the wind.

The Coriolis Effect and Ekman Transport

The story begins with the wind. In the major eastern boundary current systems—such as the California Current off North America, the Humboldt Current off South America, the Benguela Current off Africa, and the Canary Current off Europe—winds blow parallel to the coastline toward the equator.

As these winds drag across the surface of the ocean, they set the water in motion. However, the water does not move directly with the wind. Due to the Earth’s rotation, a force known as the Coriolis effect deflects the movement of the water. In the Northern Hemisphere, the water is deflected 90 degrees to the right of the wind direction. In the Southern Hemisphere, it moves 90 degrees to the left.

This net movement of water, known as Ekman transport, causes surface water to be pushed away from the coast. Nature abhors a vacuum. As the surface water is peeled away from the shoreline, it must be replaced. The only place for replacement water to come from is below.

The Reservoir of the Deep

Cold, dark water from depths of 100 to 300 meters rises to fill the void. This deep water is fundamentally different from the surface water it replaces. It has been out of contact with the atmosphere for decades, sometimes centuries. It travels slowly along the ocean floor, collecting the detritus of the marine world.

Dead plankton, fecal pellets, and decaying organic matter rain down from the surface, sinking into these deep currents. As bacteria break down this organic rain, they consume oxygen and release carbon dioxide ($CO_2$) through respiration. It is the same process that happens in a compost pile, but it occurs in the crushing dark and cold of the deep sea.

Because this water is trapped below the surface, the $CO_2$ cannot escape into the atmosphere. It accumulates. Over time, this deep water becomes a reservoir of dissolved inorganic carbon—naturally rich in nutrients (released by the decay) but also naturally acidic (due to the high $CO_2$).

When the coastal winds blow and Ekman transport engages, this nutrient-rich, carbon-loaded water is drawn up to the continental shelf and into the photic zone. In a balanced world, this is a miracle: the nutrients fuel massive phytoplankton blooms, which feed the zooplankton, which feed the fish. It is the heartbeat of coastal productivity.

But in the Anthropocene, the chemistry of this heartbeat has changed.

Part III: The Chemistry of Corrosive Waters

The chemistry of ocean acidification is often simplified as "oceans turning to acid." While true in trend, the mechanisms are more nuanced and far more dangerous than the simple lowering of pH suggests.

The Carbonate Buffer System

Seawater has a natural buffering capacity that keeps its pH stable, typically around 8.1 or 8.2. This stability is maintained by the carbonate system. When $CO_2$ dissolves in water, it reacts to form carbonic acid ($H_2CO_3$). This acid is unstable and quickly dissociates into hydrogen ions ($H^+$) and bicarbonate ions ($HCO_3^-$).

$$CO_2 + H_2O \leftrightarrow H_2CO_3 \leftrightarrow H^+ + HCO_3^-$$

The increase in hydrogen ions is what defines acidity. The more $H^+$ ions, the lower the pH. However, these hydrogen ions are looking for partners. They have a high affinity for carbonate ions ($CO_3^{2-}$). When $H^+$ meets $CO_3^{2-}$, they combine to form more bicarbonate.

This is the crucial problem. Carbonate ions are the building blocks that marine organisms—oysters, clams, corals, pteropods—need to build their shells and skeletons (calcium carbonate, $CaCO_3$). By grabbing the available carbonate ions to neutralize the acidity, the $CO_2$ effectively steals the bricks from the builders.

Saturation State ($\Omega$)

Scientists measure the corrosiveness of seawater not just by pH, but by the saturation state of calcium carbonate, denoted by the Greek symbol Omega ($\Omega$).

- When $\Omega > 1$: The water is supersaturated. Shells are stable, and organisms can build them with relative ease.

- When $\Omega < 1$: The water is undersaturated. The seawater becomes corrosive and chemically aggressive. Pure mineral calcium carbonate will begin to dissolve.

There are two common forms of calcium carbonate used by marine life: Calcite and Aragonite. Aragonite is a more soluble, more fragile crystal structure used by larval oysters, pteropods, and many corals. It dissolves much more easily than calcite. Therefore, the "Aragonite Saturation State" ($\Omega_{arag}$) is the critical threshold for coastal ecosystems.

The Age of the Water

This is where upwelling becomes a multiplier. The deep water surfacing off the coast of Oregon or Chile has been traveling the "global conveyor belt" for a long time. The water upwelling today off the Pacific Northwest may have last touched the atmosphere 30 to 50 years ago.

While it was traveling through the deep Pacific, it was accumulating respiratory $CO_2$ from decaying organic matter. This "natural" acidification means deep water typically has a pH of 7.6 or 7.7—significantly lower than the pre-industrial surface average of 8.2.

When this water hits the surface, it should ideally off-gas some of that $CO_2$. But today, the atmosphere contains 420+ ppm of $CO_2$, compared to 280 ppm a century ago. The gradient has changed. The surface water is also absorbing $CO_2$ from the air.

We are now mixing naturally corrosive deep water with surface water that is already stressed by anthropogenic carbon. The safety buffer is gone.

Part IV: The "Double Whammy" Effect

The term "ocean acidification" usually summons images of a slow, gradual decline in pH over decades. Upwelling acidification is different. It is the chemical equivalent of a flash flood.

The Synergistic Toxicity

In upwelling zones, the acidification is not gradual. It is an event-based assault. When the spring winds kick up, pH levels can plummet drastically in a matter of days or even hours.

Research from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and NOAA has quantified this "double whammy." They found that the anthropogenic $CO_2$ burden in the surface water acts as a primer. When the naturally acidic deep water rises, it mixes with this polluted surface layer. The result is a non-linear amplification.

Because the pH scale is logarithmic, a small addition of $CO_2$ to water that is already acidic causes a much larger drop in pH and saturation state than it would in alkaline water. The buffering capacity of the upwelled water is already exhausted. Every new molecule of fossil-fuel $CO_2$ added to the system hits harder.

Hypoxia: The Toxic Twin

Upwelling acidification rarely travels alone. It is almost always accompanied by hypoxia (low oxygen). The same biological decay that created the excess $CO_2$ in the deep water also consumed the oxygen.

When this water surfaces, marine organisms are hit by a two-front war.

- Acidification forces them to spend more metabolic energy to maintain their internal chemistry and build shells.

- Hypoxia robs them of the oxygen they need to generate that energy.

It is a lethal physiological squeeze. An oyster larvae trying to build a shell in corrosive water needs more oxygen to fuel its ion pumps. Instead, it gets less. This combination is often the tipping point that leads to mass mortality events.

Part V: Ground Zero – The Pacific Northwest

There is no better place to witness the reality of this crisis than the misty, evergreen coast of Oregon and Washington. This region is the "canary in the coal mine" for global coastal acidification.

The Mystery of 2007

In 2007, the multi-million dollar shellfish industry of the Pacific Northwest nearly collapsed. The crisis began at the Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery on Netarts Bay, Oregon.

Whiskey Creek is a vital artery for the industry, supplying oyster larvae ("seed") to independent growers from Mexico to Canada. But in 2007, the larvae started dying. Billions of them. The tanks would be full of swimming veligers one day, and the next, the bottom would be covered in a layer of microscopic death.

Initially, the hatchery operators, led by Sue Cudd and Mark Wiegardt, suspected bacteria. They installed expensive UV filters and scrubbed the tanks. They treated for Vibrio. Nothing worked. The larvae continued to dissolve.

Desperate, they contacted scientists at Oregon State University (OSU), including biogeochemist Burke Hales. Hales brought in equipment to monitor the water chemistry in real-time—something that hadn't been done routinely in hatcheries before.

The Smoking Gun

What they found changed the course of marine science. The die-offs weren't caused by bacteria. They were caused by the water itself.

The hatchery draws its water directly from the bay. When the north winds blew, strong upwelling events were pulling deep, corrosive water into the bay and directly into the hatchery intakes.

The data showed a direct correlation: whenever the aragonite saturation state ($\Omega_{arag}$) dropped below 1.0, the larvae died within 48 hours. The water was literally dissolving the shells of the microscopic oysters as they tried to form them.

The baby oysters are most vulnerable in the first 48 hours of life, a stage where they must build their first shell (the prodissoconch I) rapidly. To do this, they use the lipids (fats) from the egg. In corrosive water, the energy required to precipitate calcium carbonate skyrockets. The larvae burn through their energy reserves before they can finish their shell. They effectively run out of gas and die of exhaustion, or they grow deformed, unsealed shells that leave them vulnerable to infection.

The Adaptation

The discovery at Whiskey Creek was a wake-up call. It proved that ocean acidification wasn't a problem for the year 2100; it was killing industry now.

The hatchery adapted by becoming a chemistry lab. They installed "dosage" systems to inject sodium carbonate (soda ash) into the incoming water, artificially buffering the pH back to safe levels. It was a technological life-support system for the ocean. It saved the industry, but it was a terrifying lesson: we can no longer rely on the ocean to be a benign environment for life.

Part VI: Global Hotspots – Beyond North America

While the Pacific Northwest grabbed the headlines, the physics of upwelling ensures this is a global phenomenon.

The Humboldt Current (Peru & Chile)

Off the coast of South America, the Humboldt Current is the most productive marine ecosystem on Earth. It produces nearly 20% of the world’s fish catch, primarily anchoveta.

Research in Chile has shown that upwelling waters here are frequently undersaturated with aragonite. The area creates a natural laboratory where species have been dealing with low pH for millennia. However, the intensification is the concern. The scallop industry in Peru ($Argopecten purpuratus$) is particularly vulnerable. Unlike the enclosed hatcheries of Oregon, the Peruvian scallop industry relies on natural spat collection in open bays. They cannot "buffer" the ocean with soda ash.

Studies show that during strong upwelling events—which are becoming more intense—scallop larvae growth is stunted. The concern is that a threshold will be crossed where the natural resilience of these species is overwhelmed by the speed of the chemical change.

The Benguela Current (South Africa & Namibia)

The Benguela system is unique because it is bounded by warm waters on both sides. It supports a massive rock lobster and hake fishery. Here, the acidification issue is compounded by "sulphide eruptions."

The decay of organic matter on the broad continental shelf of Namibia creates not just high $CO_2$ and low oxygen, but also hydrogen sulfide gas in the sediments. When upwelling is strong, it can dredge up this toxic mix. The combination of acidification, deoxygenation, and sulphide toxicity creates "dead zones" where rock lobsters walk out of the sea onto the beach to escape the suffocating water—a phenomenon known as a "walkout."

The Canary Current (Northwest Africa & Iberia)

Off the coast of Portugal, Spain, and Morocco, the Canary Current drives the productivity of the region. The mussel rafts of Galicia (Spain) are world-famous. While the Mediterranean water influence buffers this region slightly better than the Pacific, the trend lines are the same. Increasing upwelling intensity is bringing lower pH water into the Rias (drowned river valleys) where the mussels are grown.

Part VII: The Biological Dissolution

The impact of upwelling acidification extends far beyond oysters. It strikes at the very foundation of the marine food web.

Pteropods: The Potato Chips of the Sea

Pteropods, or "sea butterflies," are tiny, swimming snails. They are a keystone species in cold waters, serving as a primary food source for salmon, herring, mackerel, and even whales.

Pteropods build their shells out of aragonite, the most soluble form of calcium carbonate. In the California Current, researchers have captured pteropods with shells that are severely pitted and dissolving. In some upwelling events, over 50% of the pteropod population shows signs of severe shell dissolution.

When a pteropod’s shell dissolves, it loses buoyancy and balance. It struggles to swim, becoming an easier target for predators or simply sinking into the abyss. If the pteropod population crashes, the ripple effects up the food chain could be catastrophic for the commercial salmon fishery.

Dungeness Crab

The Dungeness crab is the most valuable fishery on the US West Coast. For years, it was thought that crustaceans were relatively immune to acidification because their shells are made of chitin and calcite, which is stronger than aragonite.

However, recent NOAA studies (2023-2024) have shown that Dungeness crab larvae are suffering. The larvae use calcite, but they also have sensory structures (mechanoreceptors) that appear to be damaged by low pH. Furthermore, the dissolution of the shell requires the crab to divert energy from growth to repair. This results in smaller crabs and higher larval mortality.

The Hidden Cost: Metabolic Stress

For many organisms, the shell doesn't just dissolve; the animal inside burns out. This is the concept of the bioenergetic cost.

Fish, for example, are not calcifiers. They don't have shells. But they must maintain the pH of their blood within a narrow window. In high-$CO_2$ water, fish must actively pump ions across their gills to prevent acidosis. This takes energy.

In the upwelling zones of California, researchers have found that juvenile rockfish exposed to high $CO_2$ have reduced aerobic scope. They are sluggish. They don't escape predators as fast. They don't hunt as effectively. It is a silent physiological tax that reduces the overall fitness of the population.

Sensory Disruption

Perhaps the most bizarre effect of acidification is on the brain. High $CO_2$ levels interfere with the neurotransmitter receptors (GABA-A) in marine brains.

Studies on clownfish and other reef species have shown that in acidic water, they lose their fear of predators. They become attracted to the smell of their enemies. In upwelling zones, similar behavioral anomalies are being investigated in rockfish and salmon. If acidification blinds prey to the presence of predators, it destabilizes the entire ecological balance.

Part VIII: Iron and Ice – The New Frontier

Recent research published in late 2023 and 2024 has uncovered a new, terrifying mechanism: Bioavailability of Iron.

Phytoplankton (diatoms) in upwelling zones are the primary producers. They need sunlight, nitrate, and iron to grow. Iron is usually the limiting factor.

A groundbreaking study from Scripps Institution of Oceanography revealed that acidification changes the chemical speciation of iron in seawater. As pH drops, iron binds more tightly to organic ligands, making it harder for phytoplankton to absorb.

This means that even if the upwelling brings up plenty of nitrate, the "fertilizer" effect might be nullified because the plankton can't access the iron. This could lead to a shrinking of the phytoplankton blooms that support the entire ecosystem.

Furthermore, the study found that diatoms undergo stress responses in acidic water, altering their outer silica shells. The implications of this are profound: acidification might not just kill the shellfish; it might starve the ocean by suppressing the base of the food chain.

Part IX: Concrete and Steel – The Infrastructure Threat

When we speak of "coastal corrosion," the mind jumps to shells. But the chemical definition of corrosion applies to our cities, too.

Seawater is naturally corrosive to steel and concrete, which is why we have industries dedicated to marine coatings and cathodic protection. However, upwelling acidification is shifting the baseline for engineers.

The Concrete Problem

Concrete is highly alkaline (pH 12-13). Seawater is around pH 8.1. This gradient already invites chemical attack. But as coastal waters drop to pH 7.6 or 7.5 during strong upwelling events, the chemical aggression increases.

Acidic water attacks the calcium silicate hydrate (the "glue" of concrete) and the calcium hydroxide. This leads to:

- Leaching: The calcium is sucked out of the concrete matrix.

- Porosity: The concrete becomes more porous, allowing salt water to penetrate deeper.

- Rebar Corrosion: Once the saltwater reaches the steel reinforcement (rebar), it rusts. Rust expands, cracking the concrete from the inside out (spalling).

Port authorities in upwelling zones are beginning to see accelerated degradation of pilings, seawalls, and intake pipes. The service life of marine infrastructure designed for pH 8.2 may be significantly reduced in a pH 7.6 world.

Ships and Hulls

While ships are protected by advanced paints, the increased acidity impacts the antifouling coatings and the rate of corrosion on exposed metal (propellers, rudders). Naval assets operating in high-upwelling zones may require more frequent dry-docking and maintenance cycles.

For coastal power plants and desalination facilities that use seawater for cooling or feed, the change in chemistry affects the metallurgy of heat exchangers and pipes. The "corrosion allowance" calculated 30 years ago may no longer be sufficient.

Part X: The Economic Ripple Effect

The physics and chemistry inevitably crash into the economy.

The Shellfish Economy

The Pacific Northwest shellfish industry is worth over $270 million annually. It supports thousands of jobs in rural coastal communities. The 2007 crisis demonstrated that this entire sector is vulnerable to collapse.

When the hatcheries fail, the farms have no seed to plant. Two years later, there are no oysters to harvest. The gap in the supply chain bankrupts small family farms.

Fisheries and Food Security

The impacts on wild fisheries are harder to quantify but potentially larger. The Dungeness crab fishery is a huge economic driver. If larval survival drops by 30% due to shell dissolution, the catch limits must be reduced, impacting fishermen's livelihoods.

In developing nations, such as those bordering the Benguela or Humboldt currents, the threat is to food security. Artisanal fishermen rely on these upwelling zones for their daily protein. If the anchovy or sardine populations crash due to food web disruptions (plankton/pteropod declines), the human cost will be hunger.

Tourism and Culture

Coastal tourism relies on the perception of a pristine ocean. "Walkouts" of lobster, washes of dead crabs, or the smell of decaying phytoplankton blooms (often exacerbated by the nutrient imbalances) drive tourists away.

For Indigenous tribes in the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere, shellfish are not just a commodity; they are a cultural pillar. The loss of clam beds and oyster reefs is a loss of heritage and treaty rights.

Part XI: The Future Forecast – Is it Getting Worse?

The most alarming aspect of upwelling acidification is that it is self-reinforcing due to climate change.

The Bakun Hypothesis

In 1990, oceanographer Andrew Bakun proposed a controversial hypothesis: Climate change will intensify coastal upwelling.

The logic is sound:

- Greenhouse gases warm the land faster than the ocean.

- This increases the temperature difference (gradient) between the hot continent and the cool ocean.

- This pressure gradient drives the alongshore winds.

- Stronger winds mean stronger upwelling.

Decades of data have now largely confirmed the "Bakun Hypothesis." Upwelling winds are getting stronger and starting earlier in the season.

The Feedback Loop

Stronger upwelling brings up more deep, acidic water.

Simultaneously, the deep water itself is getting more acidic as the global ocean absorbs more atmospheric $CO_2$.

And finally, the surface water is warming, which increases the metabolic rate of organisms, making them require more oxygen precisely when the upwelled water has less.

Models project that by 2050, more than half of the nearshore waters in the California Current System will be undersaturated with aragonite year-round. We are moving from a regime of "episodic acidification events" to "permanent corrosiveness."

Part XII: Turning the Tide – Adaptation and Mitigation

Is there any hope? Yes. While the global solution (reducing carbon emissions) is slow, local solutions are emerging to buy time for coastal ecosystems.

1. High-Tech Hatcheries

The Whiskey Creek model has spread globally. Hatcheries now use "Burke-o-Lators" (named after Burke Hales)—sophisticated sensors that measure the saturation state in real-time. When the water turns bad, they close the intakes or buffer the water with sodium carbonate. This decoupling of the hatchery from the wild ocean is an expensive but effective stopgap.

2. Phytoremediation: Seagrass and Kelp

Plants are the natural antidote to $CO_2$. Seagrass meadows and kelp forests absorb massive amounts of carbon dioxide during photosynthesis, locally raising the pH of the water.

Pilot projects in Puget Sound and California are co-locating shellfish farms with kelp forests. The kelp creates a "halo of alkalinity" that protects the oysters growing within it. This is known as Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA). It turns pollution into product (kelp) while protecting the crop (shellfish).

3. Genetic Resilience

Evolution is working, too. Scientists are breeding "super oysters." By selecting the survivors of acidification events, they are cultivating strains of shellfish that can calcify faster or with less energy. This selective breeding is the agricultural revolution of the sea.

4. Reducing Local Pollution

We cannot easily stop the global atmospheric $CO_2$ or the deep ocean upwelling. But we can control what flows off the land.

Runoff from agriculture (fertilizers) and sewage adds nutrients to coastal waters. This causes algae blooms that die, sink, and rot—adding more $CO_2$ to the bottom water (eutrophication). By upgrading sewage treatment plants and managing farm runoff, we can remove the "local amplifier" of acidification.

5. Infrastructure Adaptation

For the built environment, the solution is materials science. New "marine-grade" concretes with lower permeability and corrosion inhibitors are being specified for ports. Cathodic protection systems are being beefed up. Engineers are learning to design for a chemically aggressive ocean.

Conclusion: The Vertical Frontline

Upwelling acidification is a complex, invisible disaster. It is a story of physics conspiring with pollution to undo the chemistry of life.

The vertical currents that have sustained human civilizations for millennia are changing. The "fertile" water is becoming "fossil" water—loaded with the carbon of our industrial past.

However, this crisis has also catalyzed a renaissance in marine science. We are monitoring the ocean with unprecedented precision. We are discovering the hidden resilience of kelp and the genetic potential of oysters. We are learning that the ocean is not a limitless sink for our waste, but a dynamic, reactive system.

The corrosion of the coastline is a warning. It tells us that the separation between the smokestack and the deep sea is an illusion. What goes up must come down—and eventually, it will well up, returning to the surface to meet us. The challenge of the next century will be to adapt to this new chemistry, protecting the blue economy and the fragile shell-builders that form the foundation of our living ocean.

Deep Dive: The Physics of the "Spoon"

Sidebar for the technically inclined reader.To visualize upwelling, imagine a cup of coffee. If you blow gently across the surface, the liquid moves. But because the Earth is spinning, the water in the ocean acts like coffee in a spinning cup.

The Ekman Spiral is the result. The surface layer moves 45 degrees to the wind. The layer below that moves a bit slower and more to the right. The layer below that, even more. The net transport of the top 100 meters of water is 90 degrees to the wind.

When this happens along a coast, the water has nowhere to go but away. It creates a "hole" at the surface. Gravity forces deep water to rush up and fill it.

Climate change is acting like a giant spoon, stirring this cup faster. As the land heats up, the thermal low-pressure systems over continents (like the US West Coast) deepen. The high pressure over the ocean remains. The wind rushes from high to low, accelerating along the coast. This "spin up" of the wind machine is what drives the intensification of corrosive upwelling.

Case Study: The "Walkouts" of Oregon

In recent years, the Oregon coast has seen a terrifying phenomenon. Crab fishermen pull up pots filled not with live Dungeness crab, but with dead bodies. Or, thousands of crabs crawl out of the water onto the beach, desperate for oxygen.

This is the intersection of Upwelling Acidification and Hypoxia.

The upwelled water is so old that it has lost its oxygen (consumed by bacteria) and gained massive $CO_2$.

When a "bolus" of this water hits the shelf, the crabs are trapped. The acidity weakens them, and the lack of oxygen suffocates them. They have no choice but to flee the water—a reversal of evolution that signals a system in total collapse.

Scientists at the new "ocean weather stations" (moorings with pH and $O_2$ sensors) are now trying to predict these events, giving fishermen warning to move their pots before the "dead water" arrives. It is the new reality of fishing in the Anthropocene.

Reference:

- https://scitechdaily.com/worse-than-predicted-coastal-waters-are-acidifying-at-an-alarming-rate/

- https://oceanographicmagazine.com/news/coastal-waters-might-be-acidifying-faster-than-expected/

- https://news.sustainability-directory.com/climate/coastal-waters-acidify-shockingly-fast-from-deep-ocean-carbon-upwelling/

- https://cawaterlibrary.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Pages-from-Rapid-Progression-of-Ocean-Acidifcation-in-the-California-Current-System.pdf

- https://www.preventionweb.net/news/imperilled-ocean-acidification-how-us-pacific-shellfish-farms-are-coping

- https://www.cencoos.org/focus-areas/oah/oa-impacts/

- https://oceanfdn.org/sites/default/files/Rapid%20Progression%20of%20Ocean%20Acidifcation%20in%20the%20California%20Current%20System.pdf

- https://www.marketplace.org/story/2022/07/05/ocean-acidification-raises-economic-concerns-shellfish-hatcheries

- https://www.us-ocb.org/multiyear-predictions-of-ocean-acidification-in-the-california-current-system/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ocean_acidification

- https://grist.org/food/2011-08-17-the-great-oyster-crash/

- https://news-oceanacidification-icc.org/2024/05/07/imperilled-by-ocean-acidification-how-us-pacific-shellfish-farms-are-coping/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20464177.2016.1247635

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309540581_Corrosion_assessment_of_infrastructure_assets_in_coastal_seas

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/11/251129044522.htm

- https://www.climate.gov/news-features/featured-images/ocean-acidification-today-and-future

- https://research.usc.edu.au/esploro/outputs/journalArticle/Climate-change-and-wind-intensification-in/99449063702621

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25693571/

- https://pollution.sustainability-directory.com/term/ocean-acidification-mitigation/

- https://news-oceanacidification-icc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/rapport-scientifique.pdf