The ancient Dacians, who inhabited the region of modern-day Romania, developed sophisticated quarrying techniques and resource management strategies, particularly evident in their extraction and use of limestone, andesite, and precious metals. Archaeological findings, especially from sites like Măgura Călanului, provide significant insights into their methods.

Quarrying Techniques and Tools:Recent discoveries, such as a unique set of 15 iron stonemason's tools found in the Măgura Călanului limestone quarry in 2022, have greatly enhanced our understanding of Dacian stoneworking before the Roman conquest. This toolkit, weighing approximately 25 pounds (almost 11-12 kg), is considered one of the most complete and varied ever found from European antiquity and likely belonged to a single master mason. The tools suggest a comprehensive range of stonemasonry techniques:

- Direct Percussion: This involved using tools like double-headed picks. Some of these picks discovered at Măgura Călanului feature a toothed edge, a design believed to be uniquely Dacian with no known Greek or Roman parallels. These toothed sides were likely instrumental in achieving the refined finish on the prismatic blocks characteristic of luxurious Dacian ashlar architecture.

- Indirect Percussion: This technique utilized flat chisels and points, which were struck with hammers.

- Stone Splitting: Dacians used splitting wedges of various sizes to break apart large stones. The wedges found in the Măgura Călanului toolkit are relatively small (150-400 grams), suggesting they were used for smaller blocks or softer limestone, requiring less force. Evidence at the quarry, such as partially split stones with uniform splitting sockets, supports this and hints at organized work teams.

- Sharpening: The toolkit also included a whetting hammer and a portable field anvil, used for cold sharpening chisels and other tools directly at the quarry. This demonstrates an innovative approach by Dacian craftsmen, potentially reducing reliance on a separate blacksmith.

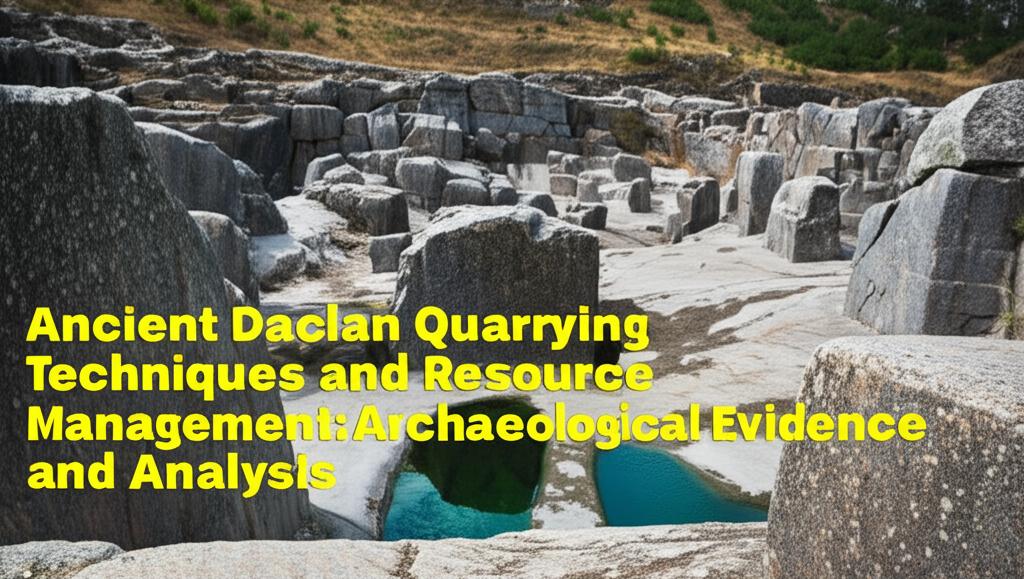

The Măgura Călanului quarry itself, spanning over 30 hectares with quarry faces up to 8 meters high, shows clear traces of these techniques, including chisel marks, signs of detachment, and stone processing. The quarrying activity here dates from the 2nd century BC until the Roman conquest in 106 AD. Other quarries, like those near Deva–Bejan (andesite) and Cheile Baciului (where a blacksmith's workshop was found), further attest to these methods. Hard rocks like basalt were also employed.

Resource Management and Significance:The Dacians managed and exploited a variety of geological resources:

- Stone for Construction: Limestone from Măgura Călanului, prized for its workability, was transported over considerable distances (e.g., 25-30 km over challenging terrain) to construct impressive fortresses, towers, temples, and paved roads, including those at the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Sarmizegetusa Regia, the capital of the Dacian Kingdom. It's estimated that approximately 10.5 million cubic meters of quarry stone were used for towns, fortresses, and roads in the province. The Piatra Roșie Dacian fortress, for example, predominantly used oolitic limestone from Măgura Călanului.

- Precious Metals: The Dacians were known for their gold and silver. While direct archaeological evidence for pre-Roman gold mines is scarce, it's believed they extracted gold primarily by washing gold-bearing sands. Significant quantities of gold were taken by the Romans after the conquest. Silver was likely extracted from pits in silver seam areas. A discovery in 1804 at Sarmizegetusa Regia of 1700 kg of galena (lead ore, often associated with silver) in large pieces suggests active mining. It is highly probable that the Dacian king held a monopoly over precious metal and iron resources.

- Iron: Iron ore was also extracted, with mines known in areas like Teliuc and Ghelari. Lemonite was extracted from open pits, while lodestone came from mines.

- Salt: Salt was another crucial resource, mainly extracted from mines in the northern regions like Ocna Mureșului, Turda, and Ocna Sibiului.

- Marble: Marble was quarried, notably from the Bucova quarry.

The strategic importance of these resources is underscored by the Roman efforts to control and exploit them after conquering Dacia. The Romans rapidly organized large-scale gold mining operations, even bringing in experienced Illyrian miners.

Archaeological Analysis and Future Research:The study of Dacian quarries and tools involves interdisciplinary approaches, including geological and archaeological investigations, mineralogical and petrographic analysis of stone, and 3D modeling to evaluate stone volumes. Modern techniques like LiDAR are used to map the extent of quarry sites.

The recent discovery of the stonemason's toolkit at Măgura Călanului is particularly significant. Although its precise dating is challenging due to its removal from its original context, the tool types are characteristic of the Dacian Kingdom (2nd century B.C. – 106 A.D.). The quarry itself shows tool marks consistent with usage patterns that ceased after the Roman withdrawal in the mid-3rd century A.D. The toolkit may have been intentionally hidden during a crisis, possibly the Roman conquest around 102 A.D.

Future research avenues include:

- Connecting the newly found tools to specific tool marks on quarry faces and semi-finished blocks.

- Conducting metallographic, microstructural, and use-wear analyses (e.g., scanning electron microscopy, mass spectrometry) on the iron tools to understand their manufacturing techniques and practical application.

- Further investigation into the organization of labor at quarry sites and the logistics of resource transportation.

These ongoing studies continue to challenge previous assumptions and provide a more detailed picture of the advanced skills, innovation, and resource management capabilities of the ancient Dacians.