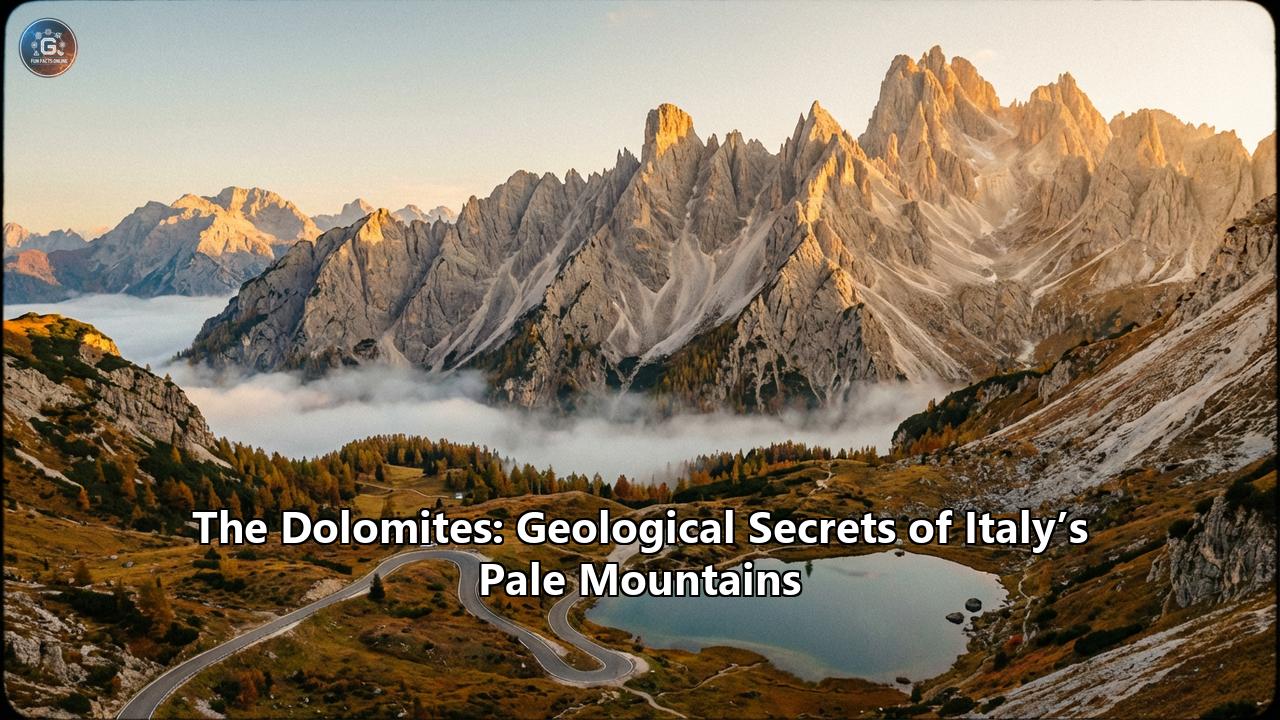

The Dolomites are not merely mountains; they are a 250-million-year-old memory of a tropical sea, thrust into the sky by the violent collisions of continents. To the casual observer, they are a playground of vertical walls and winter sports. To the geologist, they are a paradox written in stone—a "stone book" whose pages reveal the history of the earth with unparalleled clarity. To the Ladin people who have called these valleys home for millennia, they are the "Pale Mountains," a kingdom of petrified giants and sleeping legends.

This is the story of the Dolomites, from the microscopic atomic defects that birthed their unique rock to the mythical kings who allegedly cursed them to turn red at twilight.

Part I: The Birth of an Archipelago

The Tropical PrehistoryTo understand the Dolomites, one must first forget the mountains. Imagine instead a warm, shallow tropical ocean, similar to today’s Caribbean or the Maldives, located at the western edge of the vast Tethys Ocean. This was the Triassic period, roughly 240 million years ago. The supercontinent Pangea was beginning to fracture, and in this warm, sun-drenched marine environment, billions of microscopic organisms—algae, sponges, and corals—lived and died.

For millions of years, their calcium carbonate skeletons rained down onto the seafloor, accumulating in layers thousands of meters thick. These were not uniform layers; they formed massive underwater reefs and atolls, separated by deep basins. This specific geometry—towering organic reefs surrounded by deep water—is the fundamental blueprint of the Dolomites we see today. The vertical walls of the Sella Group or the Sciliar were once the steep outer edges of these ancient reefs.

The "Dolomite Problem"Here lies the first great secret of these mountains. Most carbonate reefs turn into limestone (calcium carbonate). But the Dolomites are made of dolomite (calcium magnesium carbonate). This mineral gives the mountains their characteristic pale, waxen color and their resistance to erosion.

For over two centuries, this rock baffled scientists, creating what was known as "The Dolomite Problem." In 1791, the French geologist Déodat de Dolomieu traveled to the region and noticed that this rock did not fizz when exposed to weak acid, unlike normal limestone. He sent samples to de Saussure in Geneva, who named the mineral "dolomite" in his honor.

The problem was that scientists could not reproduce this rock in a lab under normal conditions. In nature, modern oceans do not produce dolomite. So how did these massive mountains form? It wasn't until very recently, in 2023, that researchers finally cracked the code. They discovered that dolomite grows with "atomic defects." In the chaotic environment of a supersaturated solution, calcium and magnesium atoms attach randomly, creating a disordered structure that prevents further growth. Nature needs cycles of dissolution and recrystallization to "fix" these defects—a process that takes geologic eons. The Dolomites are a rare masterpiece of geochemical patience, formed by the precise alteration of limestone by magnesium-rich fluids over millions of years.

Part II: The Time Capsule

The Ladinian StageThe Dolomites are so geologically significant that they define an entire slice of Earth's time. The "Ladinian" stage of the Middle Triassic period (242–235 million years ago) is named after the Ladin people of this region.

In the valley of Bagolino, near the Caffaro river, lies the "Golden Spike" (or Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point - GSSP). This is the globally agreed-upon reference point for the beginning of the Ladinian stage. Geologists from around the world travel here to see the specific layer of rock that marks the first appearance of the ammonoid Eoprotrachyceras curionii. It is the standard by which all other rocks of this age on Earth are measured.

The Mother of All LizardsThe secrets of the Dolomites are not just mineral; they are biological. In the lush, fern-filled islands that dotted the Triassic sea, early reptiles scurried.

In the early 2000s, a fossil hunter named Michael Wachtler discovered a small, unassuming skeleton in the Braies Dolomites. It sat in a museum drawer for years until a recent study using high-resolution CT scans revealed its true significance. Named Megachirella wachtleri, this 240-million-year-old creature is the "mother of all lizards." It is the oldest known ancestor of squamates—the vast group that includes all modern lizards and snakes. Megachirella rewrote the evolutionary timeline, proving that the lineage of lizards survived the "Great Dying" extinction event (Permian-Triassic extinction) and thrived in the unique ecosystems of the proto-Dolomites.

Part III: The Nine Systems

In 2009, UNESCO declared the Dolomites a World Heritage Site. They did not list the entire range as one block, but rather selected nine specific "systems" that showcase the diversity and geological integrity of the region. Each system tells a different chapter of the story.

- Pelmo and Croda da Lago: The "God's Throne." Mount Pelmo was the first major Dolomite peak to be climbed (in 1857), and from a geological perspective, it is a perfect example of a preserved carbonate platform. Its massive, monolithic shape is a fossilized atoll.

- Marmolada: The "Queen of the Dolomites." Uniquely, the Marmolada is mostly limestone, not dolomite, which is why it hosts the largest glacier in the range. It is the highest peak (3,343m) and represents the deep-sea sediments that were later thrust upwards.

- Pale di San Martino, San Lucano, Dolomiti Bellunesi, Vette Feltrine: This vast system is arguably the most rugged. It sits on the edge of a great fault line. The Pale di San Martino plateau is a 50-square-kilometer moonscape of bare rock, a fossilized lagoon suspended 2,700 meters in the air.

- Dolomiti Friulane and d'Oltre Piave: The wildest sector. Far from the ski lifts and luxury hotels, this area is a sanctuary of silence. It is crucial for studying the "overthrust," where tectonic forces pushed older rock layers on top of younger ones.

- Northern Dolomites (Sesto, Cadore): Here lie the Three Peaks of Lavaredo (Tre Cime), the iconic symbol of the Dolomites. These three towers are not volcanic plugs but stratified sedimentary rock, eroded into vertical pillars. They show the horizontal layering of the ancient tidal flats perfectly.

- Puez-Odle: The "Geological Walk." This park is famous for the continuous exposure of rock layers. You can literally walk through millions of years of history, seeing the transition from the chaotic volcanic deposits of the mid-Triassic to the calm, orderly reefs of the later periods.

- Sciliar-Catinaccio and Latemar: The realm of legends (which we will touch upon later). The Sciliar is a massive tabular reef, while the Latemar is famous for its "theatre" of rock towers, which have provided key evidence for the cyclic nature of Triassic climates.

- Bletterbach: The "Grand Canyon of the Dolomites." This deep gorge cuts through the lower layers of the Dolomite sequence. Unlike the high peaks, Bletterbach exposes the Permian sandstones and the volcanic bedrock upon which the coral reefs were later built. It is the foundation of the entire system.

- Brenta Dolomites: The westernmost island. Separated from the main body by the Adige valley, the Brenta group is massive and imposing, holding some of the most complex stratigraphy of the entire region.

Part IV: The Human Element and the Ladin Viles

The geology of the Dolomites did not just shape the skyline; it shaped the people. The deep, U-shaped valleys carved by glaciers created islands of habitation that were cut off from the rest of Europe. In these isolated pockets, a culture survived that has vanished elsewhere: the Ladins.

The Ladin language is a direct descendant of the Vulgar Latin spoken by Roman soldiers who conquered the Alps, mixed with the indigenous Rhaetian tongue. While Italian and German evolved around them, Ladin remained preserved in the high valleys of Badia, Gardena, Fassa, Livinallongo, and Ampezzo—protected by the very walls of the Dolomites.

The Architecture of Survival: Les VilesThe unique geomorphology of the Dolomites—steep, unstable slopes and limited flat land—forced the Ladin people to develop a specific settlement pattern known as Les Viles.

Unlike the sprawling farmsteads of the Germanic north or the stone villages of the Italian south, the Viles are tight, mushroom-like clusters of houses clinging to the sunny side of the slopes. Because flat, safe land was so precious (and needed for agriculture), houses were built close together, sharing resources like fountains and ovens. This "forced community," dictated by the geological dangers of landslides and avalanches, created a deeply communal society. The architecture uses a mix of stone (for the foundation, anchored into the slope) and timber (for the upper living quarters), perfectly adapted to the local materials provided by the dolomite erosion and the coniferous forests.

Part V: Legends of the Pale Mountains

Before geologists had words like "calcium carbonate" or "lithification," the locals had their own explanations for the landscape's secrets.

The Enrosadira and King LaurinOne of the most spectacular phenomena in the Dolomites is the Enrosadira (literally "turning pink"). At dawn and dusk, the calcium and magnesium crystals in the rock catch the low-angle sunlight, causing the mountains to glow with an intense, fiery red, turning to violet before fading into the night.

The legend says that a Dwarf King named Laurin ruled the Catinaccio (Rosengarten) group. He possessed a garden of magnificent red roses. He fell in love with a human princess, Similde, and kidnapped her, using a magic cloak of invisibility. However, knights came to rescue her. They located Laurin not by seeing him, but by watching the movement of the roses as he trampled them while invisible.

Defeated and captured, Laurin cursed his rose garden for betraying him. He cast a spell so that "neither by day nor by night" would human eyes ever see the roses again. But in his anger, he forgot the twilight—the time that is neither day nor night. And so, every evening, the spell breaks for a few moments, and the bleeding color of the roses returns to the stone faces of the Catinaccio.

The Kingdom of FanesOn the high karst plateaus of the Fanes group, another legend plays out. The "Kingdom of Fanes" tells of a time when marmots and humans were allies. It is a tragic epic of Dolasilla, an invincible warrior princess who fought with white armor and magic arrows.

The legend mirrors the geology. The Fanes plateau is a "parched" landscape of white rock, filled with sinkholes and underground caves (karst). The legend tells of the "time of silence" when the kingdom was destroyed by betrayal and greed. The king, who sold out his people for gold, turned to stone and became the False King (Falzarego) pass, trapping himself in the rock forever. The survivors retreated underground into the karst caves with the marmots, waiting for the silver trumpets to sound their return.

This myth is a poetic interpretation of the landscape itself: the bleached white rocks, the whistling marmots that still inhabit the scree slopes, and the eerie silence of the high plateaus.

Conclusion: The Eternal Archipelago

The Dolomites are a convergence of worlds. They are a meeting point of the African and European tectonic plates, which buckled the crust to raise the reefs. They are a meeting point of Latin and Germanic cultures, bridged by the Ladin people. And they are a meeting point of myth and science.

When you look up at the Tre Cime di Lavaredo or the burning red wall of the Catinaccio, you are looking at a 250-million-year-old coral reef. You are looking at the "Dolomite Problem" solved. You are looking at the home of the "Mother of Lizards." And, if the light is just right and the evening is quiet, you are looking at the rose garden of a fallen king.

They are the Pale Mountains, and they hold their secrets for those willing to read the stone.

Reference:

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230815742_Urban_geology_Relationships_between_geological_setting_and_architectural_heritage_of_the_Neapolitan_area

- https://creation.com/en/articles/dolomite-problem

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.2c00078

- https://news.umich.edu/200-year-old-geology-mystery-resolved/

- https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/environment/a46318892/dolomite-problem-solved/

- https://www.suedtirolerland.it/en/highlights/tradition-and-culture/sagas-and-legends/king-laurin-and-his-rose-garden/

- https://eggental.com/en/eggental/blog/enrosadira

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Laurin

- https://perasperaadastra.it/en/blog/travel-notes/169-enrosadira

- https://drawingmatter.org/architecture-and-geology/