In the remote, verdant forests of O’ahu, Hawaii, a silent drama unfolds that rivals the grisliest scenes of a horror film. Deep within the shadows of the Waiʻanae mountain range, a creature inches along the silken threads of a spider’s web. It is not a spider, nor is it a hapless fly awaiting its doom. It is a caterpillar—a soft-bodied larva that should, by all biological conventions, be a vegetarian snack for the arachnid landlord. Yet, this caterpillar moves with impunity, invisible to the predator stalking just inches away.

It survives not by speed, nor by venom, but by wearing a coat made of death.

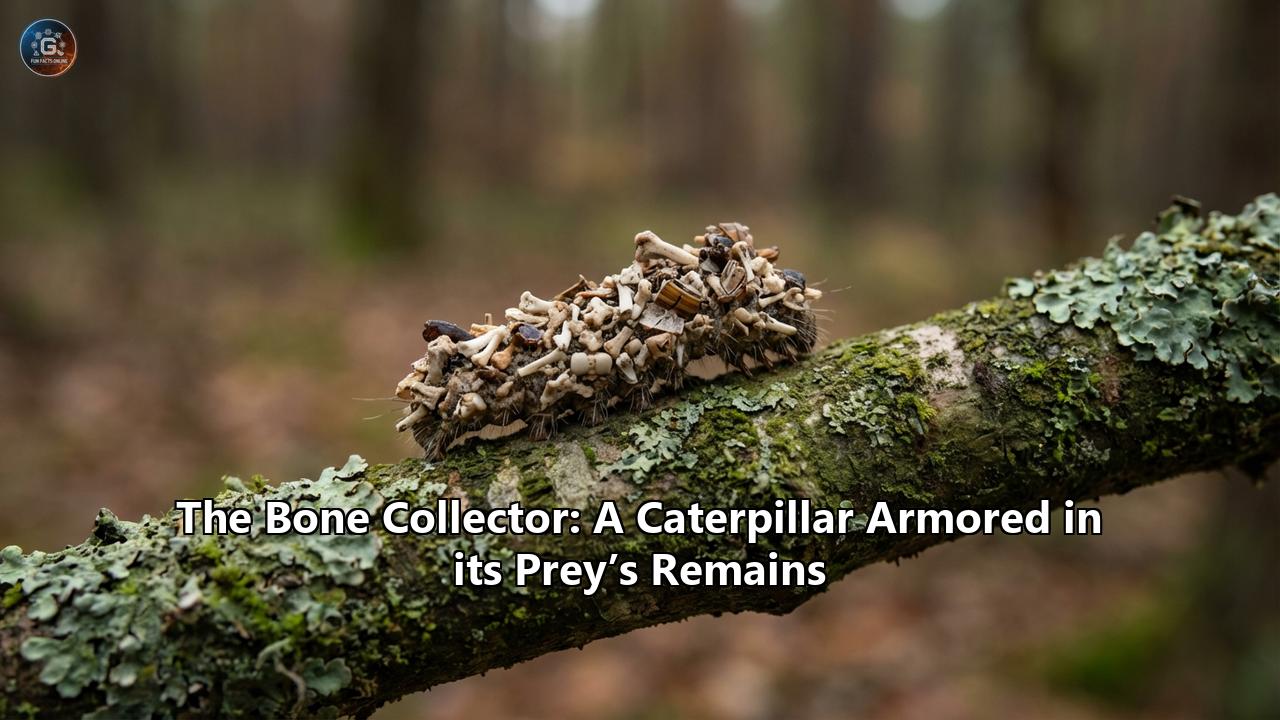

This is the Bone Collector, a newly discovered species of the genus Hyposmocoma that has stunned the scientific community with its macabre genius. Unlike its leaf-munching cousins, the Bone Collector is a carnivore, a scavenger, and a master of disguise who crafts a suit of armor from the severed heads, wings, and legs of its prey.

This article explores the fascinating, grotesque, and evolutionary brilliance of the Bone Collector caterpillar. We will journey into the isolated evolutionary laboratory of the Hawaiian archipelago, uncover the secrets of this "serial killer" of the insect world, and compare its gruesome fashion sense with other armored oddities of nature, such as the "Mad Hatterpillar" of Australia. Prepare to enter a world where the line between predator and prey is blurred by a shield of stolen skeletons.

Part I: The Discovery of a Monster

The Unlikely Habitat

For decades, entomologists have trekked through the precipitous ridges of Hawaii, documenting the islands' rich biodiversity. The genus Hyposmocoma, known as "fancy case caterpillars," was already famous for its architectural diversity. Some species build cases that look like cigars; others craft structures resembling burritos, oyster shells, or even candy wrappers. They are the master builders of the Lepidoptera world.

But one species, hiding in plain sight, defied all expectations.

Dr. Daniel Rubinoff and his team from the University of Hawaii at Mānoa stumbled upon the Bone Collector in an environment that should have been lethal: the active webs of large, predatory spiders. In the animal kingdom, a caterpillar wandering into a spider web is usually a short story with a tragic ending. Spiders are efficient killers, sensitive to the slightest vibration, capable of wrapping a victim in silk in seconds.

Yet, here was a caterpillar, casually grazing on the detritus caught in the web. It wasn't just surviving; it was thriving.

The "Bone" Armor

The secret to its survival lies in its case. Most Hyposmocoma species build their portable homes out of silk and surrounding organic matter—bits of lichen, bark, or sand—to blend into rocks or tree trunks. The Bone Collector, however, has a more specific and gruesome palette.

It builds its case exclusively from the dismembered remains of insects.

When the caterpillar finds a dead ant, a hollowed-out beetle, or a discarded fly wing in the spider's trash heap, it doesn't just eat the leftovers. It meticulously cleans the hard, chitinous parts—the exoskeletons—and weaves them into its silk shell.

- The Helmet: An ant head, mandibles still gaping, might be cemented to the front.

- The Shield: Beetle elytra (wing covers) are tiled along the flanks like shingles on a roof.

- The Camouflage: Leg segments and millipede rings are added to break up the silhouette.

The result is a walking collage of corpses. To the human eye, it looks like a pile of unappetizing trash. To a spider, whose vision is often poor and based on movement and shape, the Bone Collector is invisible. It looks exactly like the bundles of sucked-dry insect husks that litter the corners of every web. By masquerading as the spider’s own garbage, the caterpillar becomes a "wolf in sheep’s clothing"—if the sheep were made of skeletons.

Part II: The Biology of the Bone Collector

A Carnivorous Anomaly

To understand how strange the Bone Collector is, we must look at the order Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) as a whole. There are roughly 180,000 to 200,000 described species of Lepidoptera on Earth. The vast majority—over 99%—are strictly herbivorous. They co-evolved with plants, developing complex ways to digest cellulose and detoxify plant chemicals.

Carnivory in caterpillars is incredibly rare. It usually only arises in extreme isolation where resources are scarce or competition is low. Hawaii, the most isolated island chain in the world, is the perfect crucible for such evolutionary experiments.

The Bone Collector is not just a scavenger; it is an active predator when necessary, though it prefers the "lazy" route of theft. It is known as a kleptoparasite—an animal that steals food from another. It waits for the spider to catch prey, or finds insects that have died of exhaustion in the web. If a trapped insect is small or weak enough, the caterpillar may finish it off. It then feasts on the soft internal tissues, leaving the hard exoskeleton behind to be added to its collection.

The Construction Process

The behavior of the Bone Collector is not random; it is highly calculated. In laboratory settings, when presented with various materials (twigs, sand, leaves, and insect parts), the Bone Collector ignores the plant matter entirely. It shows a distinct preference for arthropod remains.

Observations suggest a high degree of craftsmanship:

- Selection: The caterpillar inspects a potential piece of armor with its mouthparts.

- Sizing: If a leg or wing is too large, the caterpillar will chew it down to fit the specific gap in its case.

- Attachment: Using silk spun from its spinnerets, it anchors the piece onto the existing tube. The silk of Hyposmocoma is incredibly strong, capable of holding these heavy adornments securely as the caterpillar drags its home across vertical surfaces.

- Molting: As the caterpillar grows, it must expand its case. It doesn't shed the old case; instead, it widens the opening and adds more material. A large, mature Bone Collector effectively wears a history of its dietary conquests on its back.

Part III: The Evolutionary Laboratory of Hawaii

Adaptive Radiation

Why does this monster exist only in Hawaii? The answer lies in the concept of adaptive radiation. When ancestors of the Hyposmocoma moths arrived in Hawaii millions of years ago (likely carried by wind), they found a paradise with few competitors. There were no ants (ants are recent invaders to Hawaii), few parasitic wasps, and plenty of open ecological niches.

Without the pressure of mainland predators and competitors, the moths exploded into hundreds of different species, each adapting to a specific lifestyle. Some became aquatic (yes, amphibious caterpillars exist in this genus), some became root borers, and others, like the Bone Collector, turned to meat.

The Bone Collector lineage is estimated to be around 6 million years old. This implies that these caterpillars were wearing insect skulls long before the island of O’ahu even finished forming. They likely hopped from older, now-eroded islands to the younger ones, carrying their bizarre traditions with them.

The Spider-Caterpillar Arms Race

Living in a spider web is a high-risk, high-reward strategy.

- The Reward: Protection from other predators. Birds and larger insects generally avoid spider webs to keep from getting sticky or bitten. By living inside the danger zone, the Bone Collector creates a fortress within a fortress. It also has a constant supply of food delivered by the spider.

- The Risk: The spider itself.

This dynamic has driven the evolution of the "trash" camouflage. If the caterpillar looked like a juicy worm, it would be eaten instantly. By looking and smelling like old, dry exoskeletons (which spiders ignore after they’ve fed), the caterpillar exploits a blind spot in the spider's behavior. It is a masquerade of the highest order.

Part IV: The "Mad Hatterpillar" – A Rival in Strange Armor

While the Bone Collector uses the remains of others, it has a rival in the world of bizarre headgear: the Uraba lugens, or the "Mad Hatterpillar," of Australia and New Zealand. To fully appreciate the Bone Collector's uniqueness, it helps to compare it to this other famous eccentric.

*The Stacked Heads of Uraba lugens---

The Mad Hatterpillar is the larva of the Gum Leaf Skeletonizer moth. Like the Bone Collector, it carries hard, chitinous objects on its head. But unlike the Bone Collector, it doesn't kill for its hat. It grows it.

Caterpillars have a hard head capsule that must be shed every time they molt (shed their skin) to grow larger. Most caterpillars flick this old head capsule away. Uraba lugens keeps it. The old, empty head capsule stays attached to the new, larger head capsule emerging underneath.

Over time, as the caterpillar goes through 4 to 5 molts, it accumulates a towering stack of empty heads, each smaller than the last, balancing like a precarious totem pole.

Function: The Weapon vs. The Shield

The Bone Collector’s armor is primarily crypsis (camouflage). It wants to vanish.

The Mad Hatterpillar’s head-stack is a distraction and a weapon.

- The Swat: When a predator, such as a stink bug or a parasitic wasp, attacks, the Mad Hatterpillar thrashes its head back and forth. The stack of dried heads acts like a club or a false target.

- The Decoy: Predators often target the head of a caterpillar to deliver a killing bite. The tall stack of empty heads confuses the attacker. A wasp might inject its eggs into the empty shell, or a stink bug might stab the hollow chitin, allowing the caterpillar to escape unharmed.

While the Mad Hatterpillar is a "collector of self," the Bone Collector is a "collector of victims." Both strategies highlight the intense pressure on caterpillars—nature's protein bars—to find any way to survive a world that wants to eat them.

Part V: Other Masters of the Macabre

The Bone Collector is the most specialized, but it is not alone in the practice of using debris for defense. The insect world is full of "trash carriers" (trash packets), though few are as gruesome.

- Green Lacewing Larvae (The Trash Bugs):

These voracious predators (often called "aphid lions") have bristles on their backs. After sucking an aphid dry, they toss the shriveled husk onto their back. Over time, they build a massive ball of gray fluff and aphid skins. This serves two purposes: physical armor against ants and olfactory camouflage. By smelling like the aphids they eat, they can walk into an ant-guarded aphid colony and slaughter the livestock without the ants realizing an intruder is present.

- Assassin Bugs (Acanthaspis petax):

This bug from East Africa specializes in hunting ants. After killing an ant and draining its fluids, it glues the corpse to its back using sticky secretions. A pile of dead ants on its back confuses visual predators like jumping spiders. The spider sees a cluster of ants (which are dangerous and usually avoided) rather than a tasty bug.

- Bagworms (Psychidae):

The most common "case bearers." Bagworms build log cabins out of twigs or sleeping bags out of leaves. However, they are strictly herbivores and use vegetation for camouflage against birds, not to hide in spider webs.

The Bone Collector stands out among these because of its specific choice of prey parts and its incredibly dangerous habitat. It isn't just hiding from birds; it is hiding from the very monster whose home it has invaded.

Part VI: The Future of the Bone Collector

A Rare and Fragile Existence

Despite its terrifying habits, the Bone Collector is vulnerable. It is currently found only in a small, 15-square-kilometer patch of forest in the Waiʻanae mountains of O’ahu. This makes it extremely susceptible to extinction.

- Invasive Species: Hawaii is under siege by invasive ants (like the Big-headed Ant) and predatory wasps that did not evolve with these native moths. These invaders may not be fooled by the "trash" disguise or may aggressively patrol trees in ways native spiders do not.

- Habitat Loss: The native forests of Hawaii are shrinking, replaced by non-native vegetation that may not support the specific micro-habitats (and specific spiders) the Bone Collector relies on.

Scientific Importance

The discovery of the Bone Collector is a reminder of how much we still don't know about the natural world. In an age where we map the genome and explore Mars, we are still finding creatures with behaviors that seem impossible.

This caterpillar challenges our understanding of:

- Cognition in Insects: The ability to select, size, and fit specific armor pieces suggests a complex sensory and behavioral loop.

- Co-evolution: The delicate dance between the spider and the caterpillar is a masterpiece of evolutionary biology. How did the first ancestor survive long enough to pass on the "don't eat me, I'm trash" gene?

Conclusion: The Beauty of the Grotesque

The Bone Collector is a paradox. To us, it is a nightmare concept—a creature that wears the faces of its victims. But in the context of evolution, it is a thing of beauty. It represents the ultimate triumph of survival.

In the dark corners of the Hawaiian forest, a small, soft larva has looked at the deadliest predator in its world and found a way to say, "I am not here." It has turned the remnants of death into a cradle of life.

So, the next time you see a cobweb in the corner of your ceiling, look closely at the little bundle of debris caught in the silk. It might just be a fly husk. Or, if you are very lucky (and in Hawaii), it might be the Bone Collector, peering out from behind a mask of stolen eyes, watching the world from the safety of its grisly armor.

Appendix: Fast Facts

- Common Name: Bone Collector Caterpillar

- Scientific Genus: Hyposmocoma (Species pending formal epithet)

- Location: O’ahu, Hawaii (endemic)

- Size: Approx. 0.5 to 1 inch

- Diet: Carnivorous/Scavenger (Dead insects, weak prey, spider leftovers)

- Armor Materials: Ant heads, beetle wings, spider skins, millipede segments.

- Known Predators: Invasive ants, wasps (Native spiders rarely eat them due to camouflage).

- Status: Extremely Rare / Endangered.

Glossary of Terms

- Crypsis: The ability of an animal to avoid observation or detection by other animals (camouflage).

- Masquerade: A type of camouflage where an organism resembles an uninteresting object (like a twig, bird dropping, or trash) rather than just blending into the background.

- Kleptoparasitism: A form of feeding in which one animal takes prey or other food from another that has caught, collected, or otherwise prepared the food.

- Instar: A developmental stage of arthropods, such as caterpillars, between each moult (shedding of the exoskeleton).

- Adaptive Radiation: The diversification of a group of organisms into forms filling different ecological niches.

Reference:

- https://www.sciencenews.org/article/caterpillar-wears-body-part-insect-prey

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PX9NLsFjExA

- https://www.sciencealert.com/bone-collector-caterpillar-wears-dead-bugs-to-steal-prey-from-spiders

- https://people.com/bone-collector-caterpillar-wears-its-prey-and-lives-among-spiders-11722515

- https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2025/04/25/bizarre-bone-collector-caterpillar/

- https://www.chipchick.com/2025/05/a-rare-carnivorous-caterpillar-that-wears-the-remains-of-other-insects-has-been-found-in-hawaii

- https://www.sciencefocus.com/news/bone-collector-caterpillar-hawaii-new-species

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/researchers-discover-a-rare-carnivorous-caterpillar-that-wears-dead-insect-parts-to-fool-spiders-180986506/

- https://news.mongabay.com/short-article/2025/05/hawaiis-bone-collector-caterpillar-wears-its-victims-to-survive/

- https://www.youtube.com/shorts/R4Y717ALDdg

- https://www.iflscience.com/newly-discovered-bone-collector-caterpillar-wears-the-bodies-of-its-prey-like-a-serial-killer-78945

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/bone-collector-caterpillar-remains-prey-scientists-say/