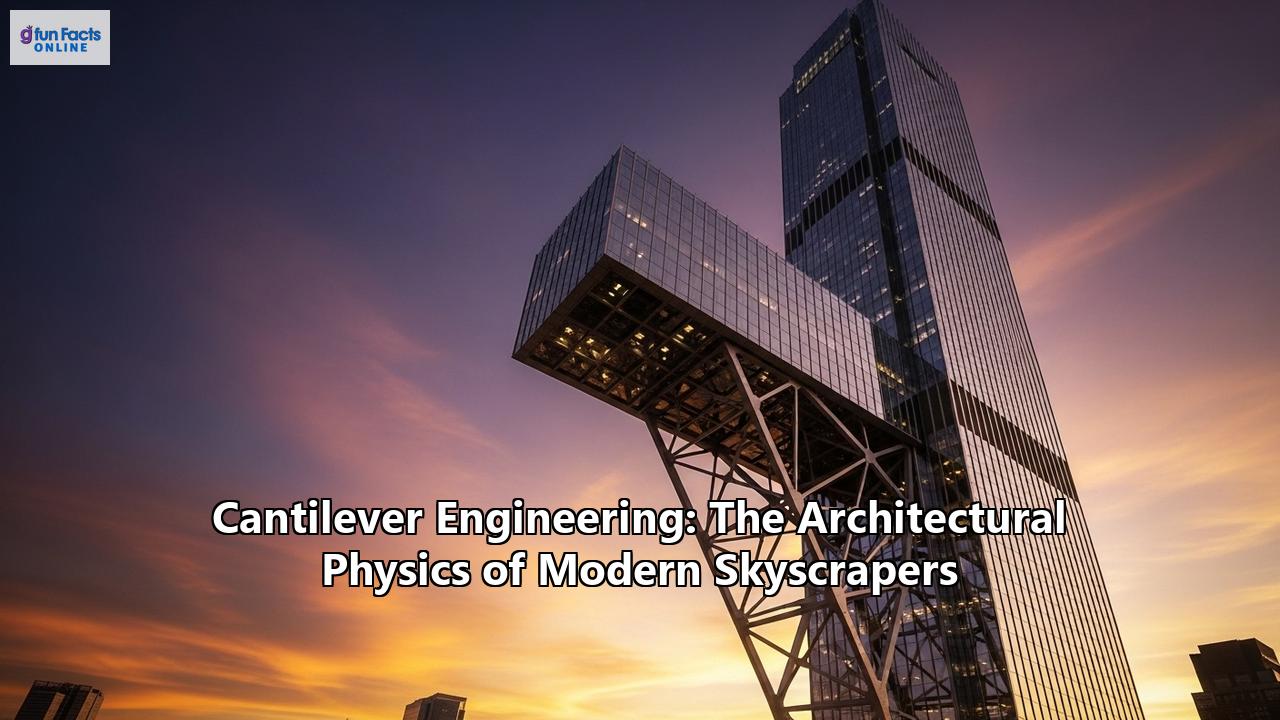

In an age where city skylines are piercing the clouds with ever-greater ambition, the modern skyscraper stands as a testament to human ingenuity. These colossal structures are not merely vertical assemblages of steel and glass; they are triumphs of physics and engineering, pushing the boundaries of what is structurally possible. Among the most dramatic and awe-inspiring feats of skyscraper design is the cantilever, a structural element that extends horizontally, seemingly in defiance of gravity. This article delves into the world of cantilever engineering, exploring the architectural physics that allow these breathtaking structures to reach for the sky, the historical evolution that paved the way for their existence, and the cutting-edge technology that continues to redefine their limits.

The Fundamental Physics of the Cantilever: A Balancing Act Against Gravity

At its core, a cantilever is a rigid structural element, such as a beam or a slab, that is anchored at only one end. This is in stark contrast to a simply supported beam, which rests on supports at both ends. The single-sided support means that a cantilever must resist the forces of gravity and any applied loads through a complex interplay of internal stresses. When a load is applied to the free end of a cantilever, it creates a bending moment and shear stress at the fixed support.

To visualize this, imagine holding a heavy book in your outstretched arm. Your shoulder acts as the fixed support, and your arm is the cantilever. You can feel the tension in the muscles on the top of your arm and the compression in the muscles on the underside. Similarly, the upper half of a cantilever beam experiences tensile stress, where the material is being pulled apart, while the lower half is subjected to compressive stress, where the material is being squeezed together. The ability of the material to withstand these opposing forces is what gives the cantilever its strength.

The length and load-bearing capacity of a cantilever are determined by three primary factors: the depth of the element, the weight it must carry, and the properties of the material from which it is made. Deeper beams are better able to resist bending, and materials like steel and reinforced concrete possess the high tensile and compressive strength necessary for long and heavily loaded cantilevers.

A Historical Trajectory: From Ancient Origins to the Dawn of the Skyscraper

The concept of the cantilever is not a modern invention. Early examples can be traced back to ancient civilizations. In traditional Chinese architecture, intricate bracket systems known as "dougong" were used to support the eaves of temples and palaces, distributing the weight of the roof and allowing for wide, overhanging structures. Similarly, ancient Greek and Roman architecture featured cantilevered balconies and eaves for both aesthetic and functional purposes, providing shade and visual interest. The corbel arches of ancient Mesopotamia also employed a rudimentary form of cantilevering.

For centuries, the use of cantilevers in building construction was limited by the available materials. The breakthrough came with the Industrial Revolution and the widespread availability of steel. In the late 19th century, engineers began to experiment with steel cantilever bridges, which could span greater distances than their predecessors without the need for intermediate supports. A pivotal moment in the history of cantilever engineering was the construction of the Forth Bridge in Scotland, completed in 1890. This iconic structure, with its three massive diamond-shaped cantilever towers, demonstrated the immense potential of steel for creating long, load-bearing spans. The success of the Forth Bridge and other cantilever bridges of the era paved the way for the application of this structural principle in buildings.

It was the visionary architect Frank Lloyd Wright who is widely credited with pioneering the use of the cantilever in residential architecture. His 1906 Robie House in Chicago featured a dramatic cantilevered roof that extended 20 feet beyond its supports, creating a sense of lightness and horizontality that was revolutionary for its time. Wright's masterpiece, Fallingwater, completed in 1937, took the concept to a new level with its iconic cantilevered terraces that seem to float effortlessly over a waterfall. These early examples, made possible by the combined strength of steel and reinforced concrete, showcased the aesthetic and spatial possibilities of the cantilever and set the stage for its adoption in the design of modern skyscrapers.

The Cantilever in Modern Skyscrapers: Reaching New Heights

In the dense urban landscapes of the 21st century, the cantilever has become a powerful tool for architects and engineers designing skyscrapers. It allows for the creation of open, column-free spaces, dramatic architectural forms, and the maximization of usable floor area, particularly in space-constrained cities like New York. Modern skyscrapers often employ a variety of structural systems to support their ambitious cantilevers.

One common approach is the use of a strong central core, typically containing elevators, stairs, and service shafts, which acts as the primary vertical support for the building. Cantilevered floors can then extend outwards from this core. To enhance the stability of these structures, especially against lateral forces like wind and seismic activity, engineers often employ outrigger systems. These are stiff horizontal structures, such as trusses or walls, that connect the central core to the perimeter columns of the building. By engaging the exterior columns, the outriggers increase the building's overall stiffness and reduce the bending moment on the core, much like a skier using their poles for balance.

For very long or heavily loaded cantilevers, steel trusses are often the preferred solution. These three-dimensional structures, composed of a network of interconnected elements, can be as deep as a full story height, providing immense strength and rigidity. Another innovative solution is the diagrid, a diagonal grid of steel members that forms a tube-like structure. This system is highly efficient at resisting both vertical and lateral loads and can create column-free interior spaces.

The materials used in cantilevered skyscrapers are as crucial as the structural systems. High-strength steel is prized for its durability, flexibility in design, and resistance to corrosion. Reinforced concrete, with its high compressive strength and fire resistance, is also a popular choice. Often, a composite of both materials is used to leverage their respective strengths.

Case Studies in Cantilever Engineering: Pushing the Limits

The relentless pursuit of architectural innovation has produced a stunning array of cantilevered skyscrapers around the globe. These buildings are not just places to live and work; they are also living laboratories of structural engineering, each with its own unique set of challenges and solutions.

One Za'abeel, Dubai: The World's Longest Cantilever

Dubai, a city known for its architectural superlatives, is home to the world's longest cantilever. One Za'abeel, a mixed-use development designed by the Japanese firm Nikken Sekkei, features a breathtaking 230-meter-long skybridge, known as "The Link," that connects its two towers. The most dramatic feature of The Link is its 67.5-meter cantilever that projects out over a six-lane highway, seemingly defying gravity at a height of 100 meters.

The engineering of One Za'abeel was a monumental undertaking. The Link, which weighs over 9,000 tons, was constructed on the ground in segments and then lifted into place in a meticulously planned operation. To accommodate the immense weight of the bridge, the two towers were intentionally built with a slight lean, so that they would be pulled into a perfectly vertical position once The Link was attached. The structural integrity of The Link is ensured by a robust diagrid system, which creates a strong and torsion-resistant tube while allowing for a column-free interior. The project also involved extensive geotechnical monitoring to ensure the stability of the ground during and after construction.

Marina Bay Sands, Singapore: A Sky Park in the Clouds

Before One Za'abeel claimed the title, the world's longest cantilever belonged to the iconic Marina Bay Sands in Singapore. Designed by architect Moshe Safdie, this integrated resort is famous for its three 55-story hotel towers connected by a 340-meter-long SkyPark. The SkyPark, which sits nearly 200 meters above the ground, features a 65-meter cantilevered observation deck that offers stunning panoramic views of the city.

The design and construction of the Marina Bay Sands cantilever presented numerous challenges. The structure had to be able to withstand the significant forces of wind and potential seismic activity at such a height. To address this, extensive dynamic studies were conducted to understand the building's potential swaying and vibration modes. The cantilever itself is a massive steel structure that was assembled in sections and lifted into place. A significant engineering feat was the design of the infinity pool that runs along the top of the SkyPark. To maintain a perfectly level edge for the infinity effect, a system of 500 hydraulic jacks was installed to compensate for the natural movement of the towers.

56 Leonard Street, New York: A Jenga-like Tower of Cantilevers

In the heart of New York's Tribeca neighborhood stands 56 Leonard Street, a residential skyscraper that has been affectionately nicknamed the "Jenga Tower." Designed by the Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron, the building is a dramatic stack of irregular, cantilevered boxes, creating a pixelated effect against the city skyline. The cantilevers range from 10 to 25 feet, resulting in a unique and varied floor plan for each of the 145 luxury apartments.

The seemingly random arrangement of the cantilevered volumes posed a significant structural challenge. The engineering team at WSP developed a solution that utilized a strong concrete structure with a central core linked to external columns by outriggers at two mechanical levels. For the smaller cantilevers, the thickness of the concrete floor slabs provides sufficient support. For the larger projections, additional beams were incorporated, and for the most extreme cantilevers, a Vierendeel truss—a frame with fixed joints that can resist bending—was used, engaging two floors without obstructing the interior space. The tower is also equipped with a slosh damper, a large tank of water at the top of the building, to counteract the effects of wind-induced movement.

The Role of Computational Tools: Designing the Impossible

The design and analysis of complex cantilevered skyscrapers would be impossible without the aid of advanced computational tools. Structural engineers rely on a suite of sophisticated software to model, simulate, and optimize these structures.

Structural Analysis and Design Software: Programs like ETABS, STAAD.Pro, and SAP2000 are industry standards for the structural analysis and design of buildings. These tools allow engineers to create detailed 3D models of skyscrapers and subject them to a wide range of load conditions, including gravity, wind, and seismic forces. They can perform complex calculations to determine the stresses, strains, and deflections throughout the structure, ensuring that it will be both safe and efficient. For more advanced analysis, particularly for complex geometries and material behaviors, engineers may use finite element analysis (FEA) software like ANSYS or S-FRAME. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD): One of the biggest challenges in designing tall, slender buildings with cantilevers is understanding and mitigating the effects of wind. Wind can cause not only significant lateral forces but also vibrations that can affect the comfort of occupants. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has become an indispensable tool for analyzing the aerodynamic performance of skyscrapers. Software like Autodesk CFD and ANSYS Fluent allows engineers to simulate the flow of air around a building, predicting wind pressures and forces on the facade. This information is crucial for designing the building's shape to minimize wind loads and for developing effective damping systems. Building Information Modeling (BIM): Modern construction projects are incredibly complex, involving the coordination of numerous disciplines. Building Information Modeling (BIM) software, such as Autodesk Revit, has revolutionized the way buildings are designed and constructed. BIM allows architects, engineers, and contractors to work on a single, integrated 3D model, improving collaboration, reducing errors, and increasing efficiency.The Future of Cantilever Engineering: Reaching for the Horizon

As cities continue to grow and densify, the demand for innovative and iconic skyscrapers will only increase. Cantilever engineering will undoubtedly play a crucial role in shaping the skylines of the future. We can expect to see several key trends emerge:

- Longer and More Daring Cantilevers: Advances in materials science, such as the development of ultra-high-strength concrete and lightweight carbon fiber composites, will enable engineers to design even longer and more audacious cantilevers.

- Smart and Responsive Structures: The integration of sensors and smart materials will allow cantilevered structures to monitor their own health in real-time and adapt to changing environmental conditions. This could lead to buildings that can actively dampen vibrations and even harvest energy from the wind.

- Sustainable Design: There will be an increased focus on the sustainability of cantilevered structures, with engineers using advanced computational tools to optimize designs for energy efficiency and minimize the use of materials.

- Integration of Green Spaces: The trend of incorporating green spaces into skyscrapers, as seen in the SkyPark at Marina Bay Sands, will likely continue, with cantilevers providing unique opportunities for elevated parks and gardens.

Cantilever engineering is more than just a structural technique; it is a form of architectural expression that allows for the creation of buildings that are both functional and breathtakingly beautiful. From the ancient temples of China to the supertall skyscrapers of Dubai, the cantilever has captivated the human imagination for centuries. As technology continues to advance, we can only imagine the incredible cantilevered structures that will grace the skylines of tomorrow, forever changing our relationship with the vertical world.

Reference:

- https://www.google.com/search?q=time+in+Dubai,+AE

- https://www.cadd.net.in/top-structural-analysis-and-design-software/

- https://avestaconsulting.net/blogs/software/top-structural-engineering-software/

- https://www.scribd.com/document/40220526/Marina-Bay-Sands-Sky-Park-Cantilever

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Marina-Bay-Sands-Singapore-Safdie-Architects-2010_fig6_318656447

- https://www.wsp.com/en-us/projects/56-leonard

- https://digitalcommons.bau.edu.lb/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1158&context=apj

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/cantilever-architecture-historical-perspective

- https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/12677-leonard-street-by-herzog-de-meuron

- https://www.encardio.com/blog/one-zaabeel-cantilever

- https://buildingspecifier.com/history-of-construction-pt-1-engineers-demonstrate-cantilever-system-in-1887/

- https://www.dezeen.com/2008/09/14/56-leonard-street-by-herzog-de-meuron/

- https://sameerabuildingconstruction.com/understanding-cantilever-beams-design-applications-and-building-structures/

- https://www.wsp.com/en-gl/projects/56-leonard

- https://misfitsarchitecture.com/2014/01/31/architectural-myths-10-the-daring-cantilever/

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/cantilever-in-architecture

- https://www.archdaily.com/tag/cantilever

- https://www.herzogdemeuron.com/projects/305-56-leonard-street/

- https://www.novatr.com/blog/structural-analysis-and-design-softwares

- https://www.archdaily.com/932623/dubais-under-construction-one-zaabeel-tower-holds-the-longest-cantilever-in-the-world

- https://newatlas.com/architecture/one-zaabeel-nikken-sekkei/

- https://fastcompanyme.com/co-design/inside-the-making-of-the-worlds-longest-cantilever/

- https://www.builtconstructions.in/OnlineMagazine/BuiltConstructions/Pages/Marina-Bay-Sands,-Singapore-0226.aspx

- https://www.tonygee.com/our-work/marina-bay-sands

- https://www.engineering.com/marina-bay-sands-unique-design-an-engineering-marvel/

- https://altair.com/structural-engineering

- https://www.azobuild.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=8724

- https://www.researchgate.net/post/Which-is-the-most-user-friendly-and-accurate-software-for-CFD-application-on-buildings

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316487682_The_Application_of_Using_Computational_Fluid_Dynamic_CFD_To_Modern_Building_Design

- https://www.simscale.com/blog/cfd-simulation-aec/

- https://dokmimarlik.com/en/evolution-of-skyscraper-design/