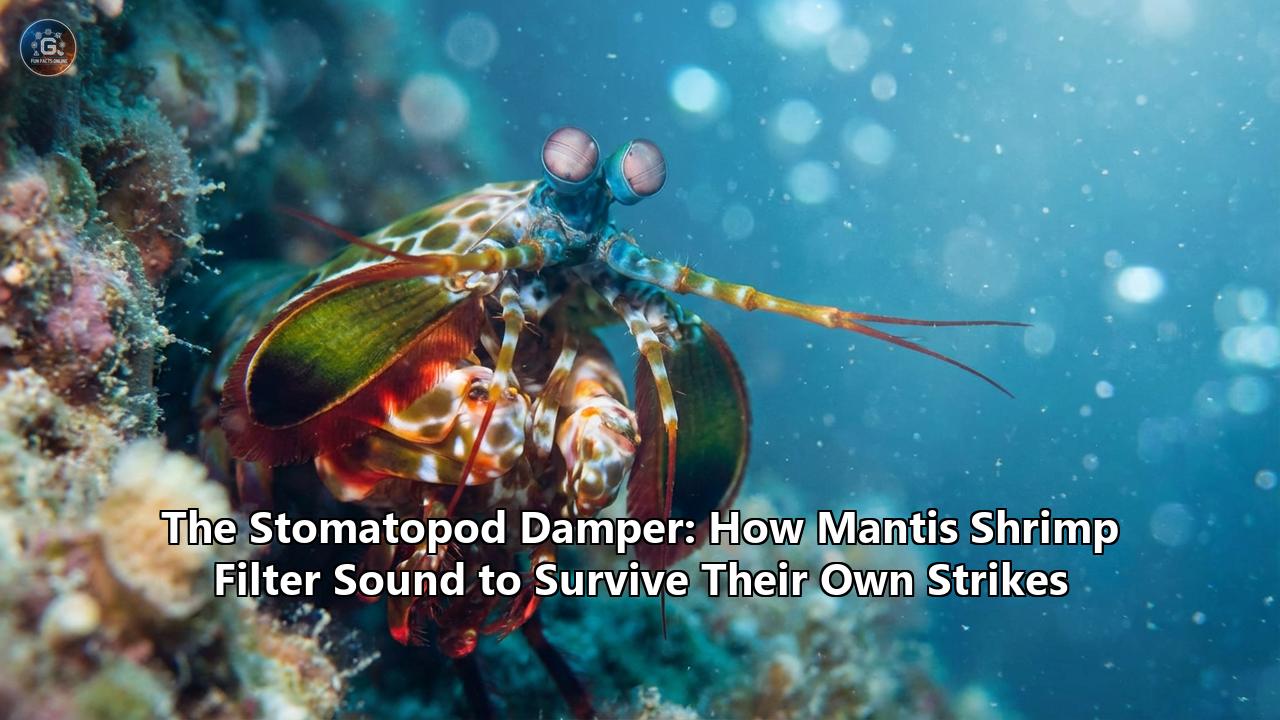

In the warm, shallow waters of the Indo-Pacific, a creature no larger than a cigar stalks the coral reefs. To the casual observer, the peacock mantis shrimp (Odontodactylus scyllarus) appears to be a flamboyant, if somewhat alien, crustacean. Its carapace is a riot of electric blues, vibrant greens, and alarm-fire reds, and its stalked eyes swivel independently with a robotic precision that suggests a calculating intelligence. But beneath this psychedelic exterior lies a weapon of such terrifying power that it breaks the conventional rules of biology and physics.

The mantis shrimp is the "Mike Tyson of the sea," a title it has earned through a strike that is arguably the most extreme movement in the animal kingdom. When it spots a crab, a snail, or a rival, it unleashes a pair of hinged raptorial appendages—its "dactyl clubs"—with the acceleration of a .22 caliber bullet. The strike occurs so rapidly that the human eye cannot register it; one moment the shrimp is still, and the next, its target is shattered.

The numbers are staggering. The club accelerates at over 10,000 g (gravity), reaching speeds of 23 meters per second (50 mph) in less than a thousandth of a second. upon impact, it delivers a force of 1,500 Newtons—more than 2,500 times the animal's own body weight. If a human could accelerate their arm at the same rate, they could throw a baseball into orbit.

But this incredible superpower presents a lethal paradox, one that has puzzled biomechanists and materials scientists for decades. According to Newton’s Third Law of Motion, for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. When the mantis shrimp strikes a granite-hard snail shell with enough force to vaporize water and generate a flash of light, that same force is instantly reflected back into the shrimp’s own arm.

By all logic, the mantis shrimp should shatter its own limb with every punch. The shockwaves generated by the impact, combined with the catastrophic collapse of cavitation bubbles, should pulverize the microscopic structures of its club, tearing muscles and snapping tendons. Yet, the shrimp strikes thousands of times over its lifetime, cracking open the hardest shells in the ocean without sustaining a scratch.

The secret to this impossibility is not just "hard armor." It is something far more sophisticated, a mechanism that borders on science fiction. Recent discoveries have revealed that the mantis shrimp possesses a biological "damper"—a specialized structure that acts as a "phononic shield." This shield does not just block force; it actively filters sound. It manipulates the laws of physics to strip away the damaging frequencies of the shockwave, allowing the shrimp to punch with impunity.

This is the story of the Stomatopod Damper—a masterpiece of evolutionary engineering that uses advanced acoustics, quantum-like physics, and material architecture to survive the deadliest punch on Earth.

II. The Physics of the "Suicide Strike"To understand the brilliance of the mantis shrimp’s defense, we must first appreciate the violence of its offense. The strike is not powered by muscle alone. Muscles, no matter how strong, are limited by the speed at which they can contract. To break the "muscle speed limit," the mantis shrimp uses a spring-loaded mechanism, similar to a crossbow or a mousetrap.

The shrimp possesses a saddle-shaped structure in its arm called a "hyperbolic paraboloid," which acts as a biological spring. Large muscles slowly compress this spring, storing immense potential energy. When the latch is released, the spring uncoils, swinging the dactyl club forward with an acceleration that defies belief.

The Double Impact: CavitationThe strike is so fast that it creates a localized area of low pressure behind the club, dropping below the vapor pressure of water. This causes the water to literally rip apart, forming cavitation bubbles—voids of vapor in the liquid. These bubbles are unstable. As the water pressure crashes back down upon them, they collapse with catastrophic violence.

This collapse generates a secondary shockwave, often as powerful as the initial physical impact. The implosion releases a tremendous amount of energy in the form of heat, sound, and light. Temperatures inside the collapsing bubble can reach 4,400 degrees Celsius (nearly as hot as the surface of the sun), and the release of energy produces a flash of light known as "sonoluminescence" or "shrimp luminescence."

For the prey, this is a double tap. If the physical blow of the club doesn't crack the shell, the subsequent cavitation blast often will. But for the shrimp, this is a double threat. It must survive the recoil of the physical impact and the omnidirectional shockwave of the cavitation bubble, which explodes mere millimeters from its own appendage.

The Danger of Shear WavesThe most dangerous component of this recoil is not the compressive force (pushing in), but the "shear waves." Compressive waves travel through a material by compressing it, which most hard materials can handle well. Shear waves, however, move by sliding layers of material past each other. They cause tearing, delamination, and structural failure.

In a biological structure made of fibers (like the shrimp's club), shear waves are devastating. They threaten to rip the layers of the armor apart from the inside out. If these high-frequency shear waves were allowed to propagate through the club and into the shrimp's softer tissues, they would shred the animal's muscles and nerves. The shrimp would essentially be punching its own arm off from the inside.

III. The Discovery: A Phononic ShieldFor years, scientists believed the secret lay solely in the club's hardness. They analyzed the mineral content, finding high concentrations of hydroxyapatite (the same mineral in human bone) and amorphous calcium carbonate. But hardness alone cannot explain the resistance to shear waves. Hard materials are often brittle; they shatter under high-frequency vibration.

The breakthrough came in early 2025, when a team of researchers from Northwestern University, led by Horacio D. Espinosa, utilized advanced laser ultrasonics and computer simulations to look deeper than the chemistry—into the geometry of the club.

They discovered that the mantis shrimp employs "phononic mechanisms." In physics, a phononic crystal is a synthetic material designed to control the flow of sound and heat. It works by having a periodic structure (a repeating pattern) that creates "bandgaps." A bandgap is a range of frequencies that cannot pass through the material. Any vibration within that frequency range is simply stopped—reflected or dissipated—because the material’s structure effectively forbids it from existing there.

The researchers found that the mantis shrimp’s dactyl club is a natural phononic crystal. It has evolved a specific microscopic architecture that creates a "phononic bandgap" tuned exactly to the frequencies of the dangerous shear waves generated by its strike.

The Damper MechanismWhen the shrimp strikes, the impact generates a chaotic storm of vibrations. Some are low-frequency (safe), but others are high-frequency shear waves (lethal). As these waves travel from the impact surface into the core of the club, they hit the "damper"—a region of the club with a specific, twisting structure.

This structure filters the waves. It allows the safe, low-frequency waves to pass through (which the shrimp might use for sensory feedback), but it completely blocks the high-frequency shear waves. The energy of these dangerous waves is trapped and dissipated within the armor, preventing it from reaching the delicate soft tissues of the arm.

The mantis shrimp is wearing a "soundproof vest." It doesn't just block the physical blow; it silences the lethal noise of the impact before it can do harm.

IV. Anatomy of a Super-Weapon: The Bouligand StructureTo create this phononic shield, nature evolved a structure that engineers call a "Bouligand structure." It is named after Yves Bouligand, who first described the architecture, but the mantis shrimp perfected it millions of years ago.

The dactyl club is composed of three distinct regions, each with a specialized role in the damper system.

1. The Impact Region (The Diamond Cap)The very outer layer of the club is the "impact region." This is the business end of the weapon. It is composed of highly mineralized hydroxyapatite crystals arranged in a "herringbone" pattern. This pattern is unique to the impact surface. It is incredibly hard and stiff, designed to deliver the maximum amount of energy to the prey without deforming. The herringbone structure also serves as the first line of defense, deflecting cracks and preventing them from propagating straight into the club.

2. The Periodic Region (The Phononic Filter)Beneath the hard outer cap lies the "periodic region," and this is where the magic happens. This region is made of chitin fibers (a polysaccharide found in insect shells) mineralized with amorphous calcium carbonate.

The fibers are not laid down in straight lines. Instead, they are stacked in sheets. Each sheet is rotated slightly relative to the one below it, creating a twisted, helicoidal structure—like a spiral staircase or a corkscrew.

This helicoidal arrangement is the Bouligand structure.

- Periodicity: The "twist" of the spiral repeats at regular intervals (the "pitch").

- Chirality: The spiral has a "handedness" (it twists in a specific direction).

This twisting architecture is what creates the phononic bandgap. As a shear wave tries to travel through this spiral, it encounters a constantly changing orientation of fibers. The wave is forced to change direction continuously. For certain frequencies (specifically the damaging high frequencies), the wave cannot navigate the twist. It becomes "frustrated" and is reflected or scattered.

The Northwestern study revealed that the specific "pitch" (the distance for one full 360-degree rotation of the fibers) is evolutionarily tuned. It is the exact dimension required to filter out the shear waves produced by the cavitation collapse. If the pitch were slightly tighter or looser, the shield would fail, and the shrimp would be injured.

3. The Striated Region (The Containment)On the sides of the club is the "striated region." This area contains parallel fibers that wrap around the club, acting like tape wrapped around a boxer’s hands. This region prevents the club from expanding outward under the immense pressure of the impact, keeping the periodic region compressed and intact.

V. Evolutionary Origins: The Arms RaceThe Stomatopod Damper did not appear overnight. It is the result of a 400-million-year evolutionary arms race. Stomatopods diverged from other crustaceans (like crabs and shrimp) long before the dinosaurs appeared.

Smashers vs. SpearersOriginally, all mantis shrimp were likely "spearers." These species, which still exist today, have spiny appendages designed to snag soft-bodied prey like fish. Spearers are stealthy ambush predators that hide in soft sand. They strike fast, but they don't hit hard objects, so they don't need heavy armor or phononic dampers.

However, during the Mesozoic Era, a new food source became abundant: hard-shelled mollusks and crabs. To access this nutrient-rich resource, a lineage of stomatopods began to evolve a different strategy. Instead of snagging, they started smashing.

This transition from "spear" to "club" created a massive evolutionary pressure. The harder the shrimp hit, the more food it got—but the more damage it did to itself. The shrimp that could withstand their own strikes survived; those that shattered their arms starved. This selective pressure drove the evolution of the club from a simple chitinous bump into the complex, mineralized, phononic crystal we see today.

The Telson ConnectionThe evolution of the damper wasn't just about eating snails. It was also about fighting each other. Mantis shrimp are fiercely territorial. They live in burrows in coral rock, which are scarce and valuable real estate.

When two "smashers" fight for a burrow, they engage in a behavior called "telson sparring." The defender curls into a ball, presenting its "telson" (the armored tail plate) as a shield. The aggressor then unleashes full-power strikes against the defender's telson.

The telson, like the dactyl club, contains the energy-absorbing Bouligand structure. It essentially acts as a catcher's mitt for the club's baseball pitch. This ritualized combat means that mantis shrimp have evolved to be both the "unstoppable force" and the "immovable object." The damper in the club protects the attacker, while the damper in the telson protects the defender. It is a mutually assured survival strategy, allowing them to resolve conflicts without death.

VI. The Alien Intelligence: Vision and PrecisionThe damper allows the shrimp to strike, but it is the shrimp's sensory systems that ensure the strike connects. The mantis shrimp’s eyes are as famous as its punch. While humans have three color receptors (red, green, blue), the mantis shrimp has 16.

They can see ultraviolet light, polarized light, and circularly polarized light. This visual system allows them to detect the contrast of prey against the reef, even in murky water. But more importantly, it allows them to see stress.

Some researchers hypothesize that the polarized vision allows mantis shrimp to see the mechanical stress patterns in the shells of their prey (or the telsons of their rivals). They may be able to target the weak points in a snail's shell, ensuring that their expensive biological strike is not wasted.

The coordination required to aim a strike moving at 50 mph, correct for the refraction of water, and hit a specific millimeter-wide target is immense. The shrimp’s brain, though small, is a dedicated ballistic computer. Once the target is locked, the strike is committed; there is no steering mid-punch. The damping system ensures that even if they miss and hit a rock (or the glass of an aquarium), the arm survives.

VII. Biomimetics: From Shrimp to SoldierThe discovery of the Stomatopod Damper has sent shockwaves through the engineering world. We are currently in a "golden age" of biomimetics—stealing design ideas from nature—and the mantis shrimp is the crown jewel.

The Problem with Man-Made ArmorHuman armor usually works by bulk. Kevlar works by catching the bullet in a web of fibers; ceramic plates work by shattering to dissipate energy. But most human armor is heavy, and it degrades quickly after impact. A ceramic plate can stop a bullet, but it usually shatters in the process and cannot stop a second one.

The mantis shrimp club can strike thousands of times without failing. It is "damage tolerant."

Helicoid IndustriesCompanies like Helicoid Industries are already commercializing this technology. By mimicking the Bouligand structure (the twisted stacking of fibers), they are creating composite materials that are lighter and stronger than traditional carbon fiber.

- Aerospace: Airplane wings made with "shrimp-structure" composites are more resistant to impact from birds or debris. They don't crack catastrophically; the cracks twist and stall, just like in the shrimp's club.

- Wind Turbines: Wind turbine blades suffer from erosion and fatigue. Helicoid composites can extend their lifespan, reducing the cost of renewable energy.

- Sports Equipment: A hockey stick or a bicycle helmet designed with a phononic shield could absorb impacts better, protecting the athlete’s brain from shockwaves (concussions) just as the shrimp protects its own arm.

- Defense: The Holy Grail is body armor that is thin, light, and capable of withstanding multiple hits. The "shear wave filtering" property of the shrimp club is exactly what is needed to stop the blunt-force trauma that often kills soldiers even if the bullet is stopped.

Where does the mantis shrimp rank in the pantheon of biological super-materials?

- Spider Silk: Long held as the champion, spider silk is incredibly strong (high tensile strength) and elastic. It is tougher than steel by weight. However, it is soft. It cannot deliver a blow.

- Limpet Teeth: In 2015, researchers discovered that the teeth of limpets (aquatic snails) are actually the strongest biological material known, beating spider silk. They are made of goethite nanofibers and are incredibly stiff to scrape rock.

- The Mantis Shrimp Club: While limpet teeth may be stronger (harder to pull apart), the mantis shrimp club is the king of toughness and damping. Strength is resisting breaking; toughness is absorbing energy. The shrimp club combines extreme hardness (impact surface) with extreme energy absorption (phononic core). It is a composite material, much more complex than the single-material limpet tooth.

The mantis shrimp is unique because it is an active material. It doesn't just sit there; it interacts with the physics of waves to filter its own reality.

IX. Conclusion: The Masterpiece of the ReefThe peacock mantis shrimp is more than just a pretty face or a viral internet meme. It is a walking (or swimming) lesson in advanced physics.

For 400 million years, this creature has been refining a technology that humans are only just beginning to understand. It has solved the problem of self-destruction through geometry. It has turned the spiral—one of nature’s favorite shapes—into a high-tech shield that filters sound and stops shockwaves.

As we look to the future of materials science, we are finding that the answers to our hardest problems—how to build safer cars, better planes, and stronger armor—are already swimming around in the coral reefs, punching snails with the force of a bullet. The Stomatopod Damper reminds us that nature is the ultimate engineer, and evolution is the longest-running research and development program on Earth.

Reference:

- https://pateklab.biology.duke.edu/research/mechanics-of-ultrafast-movement/mechanics-of-movement-mantis-shrimp/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mantis_shrimp

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EKcK73UBW5I

- https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/mantis-shrimp-inspires-next-generation-ultra-strong-materials

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QY4AEubKFh0

- https://northbaycorvettes.com/spearer-mantis-shrimp-vs-smashing-mantis-shrimp-what-makes-them-different/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=npz3svrAG8E

- https://helicoidind.com/technology.html

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/facts/mantis-shrimp

- https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Odontodactylus_scyllarus/

- https://www.livescience.com/52273-mantis-shrimp-ritual-sparring.html

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/spider-silk-loses-top-spot-natures-strongest-material-snails-teeth-180954346/

- https://www.livescience.com/49844-limpet-teeth-strongest-natural-material.html

- https://www.comsol.com/blogs/exploring-the-natural-strength-of-limpet-teeth

- https://www.irishtimes.com/news/science/limpet-teeth-overtake-spider-silk-as-strongest-biological-material-1.2107443