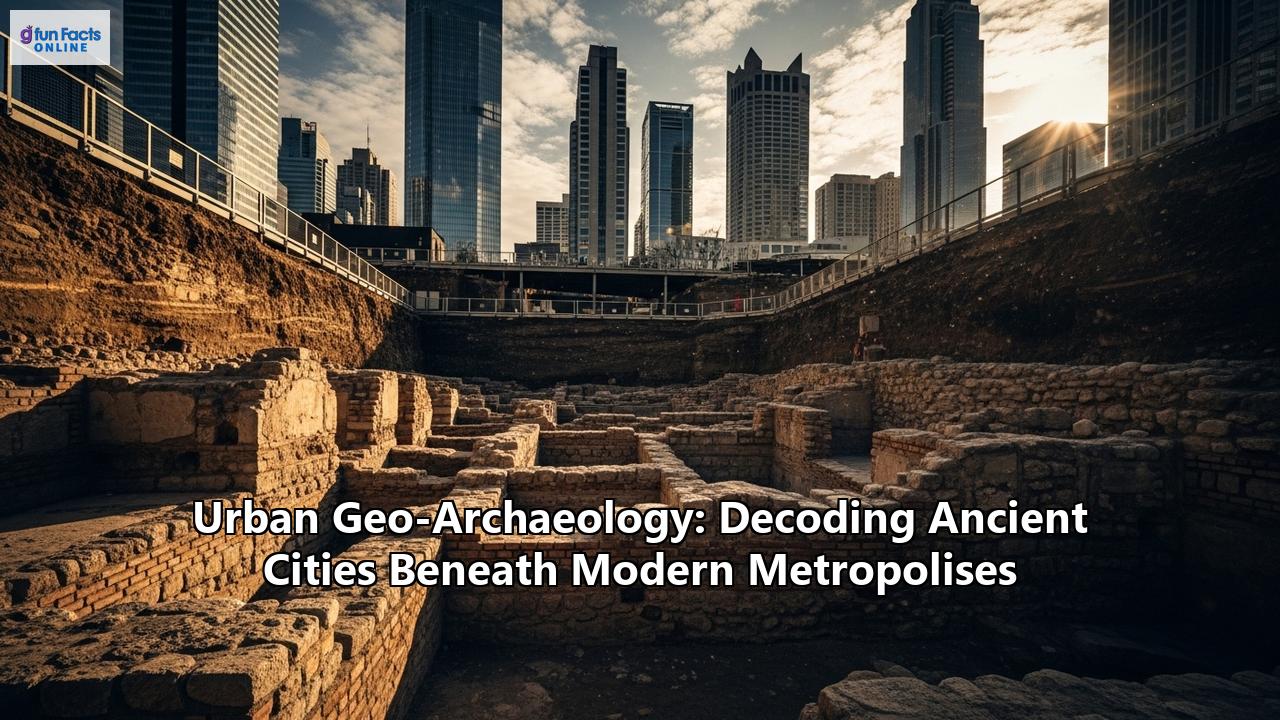

Beneath the bustling streets and towering skyscrapers of our modern cities lies a hidden world, a silent testament to the countless generations that have walked these same paths. These are the realms of ancient cities, buried but not entirely lost, their stories preserved in the very soil and sediment upon which our metropolises are built. Unearthing these stories is the work of a fascinating and complex discipline: urban geo-archaeology. It is a field that peels back the layers of time, not just to reveal individual artifacts, but to decode the very DNA of cities – their growth, their daily life, their relationship with the environment, and their ultimate transformation.

This is not the archaeology of remote, abandoned ruins, but a science conducted amidst the cacophony of urban life, in the basements of office blocks, beneath the rumble of subway lines, and in the shadow of new construction. It is a discipline that requires not only the keen eye of an archaeologist and the analytical mind of a geologist but also the deft negotiation skills of a diplomat and the forward-thinking vision of a city planner. Urban geo-archaeology is where the past and present collide, and where the lessons of ancient civilizations can inform the sustainable future of our own urban world.

The Foundations of Urban Geo-Archaeology: A Hybrid Science

At its core, urban geo-archaeology is an interdisciplinary field that merges the principles of geology with the investigative methods of archaeology. While traditional archaeology focuses on the material culture of past societies, geo-archaeology delves into the physical context of those remains. It examines the soils, sediments, and landforms that make up an archaeological site to understand its formation and the environmental conditions that prevailed in the past.

In an urban context, this becomes exponentially more complex. Cities are dynamic environments where human activity has profoundly reshaped the natural landscape. The ground beneath a city is a complex tapestry of natural geology and anthropogenic deposits – the accumulated layers of human occupation. These "urban soils" or "anthrosols" are a rich archive of a city's history, containing everything from building materials and household waste to the microscopic traces of ancient industries and diets.

The primary goal of urban geo-archaeology is to read this complex archive. By studying the stratigraphy – the layering of deposits over time – geo-archaeologists can reconstruct the history of a site in incredible detail. They can identify the sequence of construction, demolition, and rebuilding that characterizes urban life. They can differentiate between periods of intensive occupation and periods of abandonment or decline. And by analyzing the composition of the soil and sediments, they can paint a vivid picture of the past environment and how it was modified by human hands.

One of the key concepts in urban geo-archaeology is the "tell" or "mound," a feature common in the ancient Near East and Mediterranean basin. These mounds are the result of centuries, or even millennia, of continuous settlement, where new structures were built on top of the ruins of older ones, creating a stratified sequence of occupation layers. While not all ancient cities formed tells in the classic sense, the principle of vertical accumulation is a universal feature of long-occupied urban sites. This "urban stratification" is the primary evidence that geo-archaeologists seek to understand.

The Geo-Archaeologist's Toolkit: Peering Beneath the Pavement

Excavating in a dense urban environment is a far cry from a traditional dig in an open field. The constraints of modern infrastructure, the high cost of land, and the pressures of development mean that archaeologists often have limited time and space to work with. As a result, urban geo-archaeology has become a pioneer in the use of non-invasive and minimally invasive techniques to explore the subsurface.

Geophysical Surveying: The Art of Remote SensingBefore a single spade breaks the ground, geo-archaeologists often deploy an arsenal of geophysical survey techniques to map what lies beneath. These methods use various physical properties of the earth to detect buried features without the need for excavation.

- Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR): This is one of the most widely used techniques in urban archaeology. GPR sends pulses of radar energy into the ground and records the reflections that bounce back from different materials. It can detect buried walls, foundations, floors, and even voids like tunnels or tombs. The data can be processed to create 3D maps of the subsurface, providing a virtual "fly-through" of the buried archaeology. GPR is particularly valuable in urban settings because it is less affected by the metal pipes and cables that can interfere with other geophysical methods. Case studies from Belgrade, Serbia, and Crete, Greece, have demonstrated the effectiveness of GPR in identifying significant archaeological structures in complex urban environments, guiding subsequent excavations and informing construction projects.

- Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT): This technique measures the resistance of the soil to an electrical current. Different materials have different levels of resistance, so by mapping these variations, archaeologists can identify buried features. For example, a stone wall will have a much higher resistance than the surrounding soil. ERT is often used in conjunction with GPR to provide a more complete picture of the subsurface. In Padua, Italy, ERT and GPR were used to investigate the remains of a Roman theatre, providing new details about its extent and location in a challenging urban environment.

- Magnetometry: This method detects minute variations in the Earth's magnetic field caused by buried features. Fired materials like bricks, hearths, and kilns have a strong magnetic signature, making them easily detectable with a magnetometer. While magnetic surveys can be affected by the abundance of metal in urban areas, they can still be highly effective in certain contexts.

Beyond looking beneath the ground, urban geo-archaeologists also employ advanced technologies to document the visible world with unprecedented accuracy.

- LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging): Often deployed from aircraft or drones, LiDAR uses laser pulses to create highly detailed 3D maps of the landscape. By filtering out vegetation, LiDAR can reveal the "bare earth" topography, uncovering subtle features like ancient roads, canals, and building foundations that are invisible to the naked eye. This has been particularly revolutionary in mapping the extent of ancient urban networks, such as the sprawling medieval city of Angkor Wat in Cambodia and the newly discovered Mayan cities in Central America.

- Terrestrial 3D Laser Scanning: On a smaller scale, terrestrial laser scanners are used to create incredibly precise 3D models of excavation sites, individual structures, and even artifacts. This technology is crucial for documenting the complex stratigraphy of urban excavations, allowing archaeologists to revisit and analyze the site virtually long after the excavation has been backfilled. In Chicago, 3D laser scanning has been used to track the progress of deep urban excavations, integrating the as-built data with geotechnical monitoring to ensure the stability of surrounding structures. This highlights the dual role of this technology in both archaeological documentation and modern construction management. The use of 3D laser scanning in preserving fragile artifacts, such as those from Pompeii, also demonstrates its value in creating digital replicas for study and public engagement.

The story of a city is not just written in its grand monuments, but also in the microscopic composition of its soil. This is where the techniques of soil micromorphology and geochemical analysis come into play.

- Soil Micromorphology: This involves taking intact blocks of soil from an archaeological deposit, impregnating them with resin, and then slicing them into thin sections that can be examined under a microscope. This technique allows geo-archaeologists to see the microscopic structure of the soil, revealing a wealth of information about how it was formed. They can identify individual layers of ash from ancient fires, trampled floor surfaces, the remains of decomposed organic materials like wood and textiles, and even the microscopic traces of industrial processes. Studies of "dark earth" – thick, dark, and seemingly uniform layers of soil found in many European cities – have used micromorphology to reveal their complex origins as a mixture of household waste, building debris, and garden soils, providing a detailed picture of waste management and land use in medieval cities like Antwerp and Oudenaarde in Belgium.

- Geochemical Analysis: This involves analyzing the chemical composition of soil samples to identify traces of past human activities. For example, high concentrations of phosphates can indicate the presence of human or animal waste, while elevated levels of heavy metals can point to ancient industrial activities like metalworking. By systematically taking soil samples across a site and analyzing their chemical makeup, archaeologists can create a "chemical map" of past land use, identifying areas of domestic activity, craft production, and agriculture. Geochemical surveys can be a rapid and cost-effective way to evaluate the archaeological potential of a site before excavation.

Tales of the Unexpected: Unearthing Ancient Cities

The application of these sophisticated techniques has led to some of the most spectacular archaeological discoveries in recent memory, fundamentally changing our understanding of ancient urbanism.

Rome: Beyond the ForumThe city of Rome is, in many ways, the quintessential urban archaeological site. While the monumental remains of the Roman Forum have always been visible, urban geo-archaeology has allowed researchers to delve deeper into the city's 3,000-year history. Excavations at the Caesar's Forum, for example, have not only provided new insights into the Roman period but have also uncovered the remains of the medieval and Renaissance-era Alessandrino Quarter, a neighborhood that was demolished in the 1930s to make way for Mussolini's Via dei Fori Imperiali. This project highlights the importance of studying all layers of a city's history, not just the most famous ones. The use of 3D modeling and data sharing has been crucial in documenting the complex stratigraphy of the site and making the findings accessible to a wider audience. Investigations at the foot of the Palatine Hill have revealed an even longer history, with evidence of a pre-urban settlement dating back to the 11th century BCE, as well as the remains of the Palatine Wall from the 8th century BCE.

London: From Londinium to the MegacityThe City of London, the financial heart of the modern metropolis, sits atop the remains of the Roman city of Londinium. For decades, the constant cycle of demolition and redevelopment has provided archaeologists with unique opportunities to glimpse this hidden past. A prime example of this is the recent discovery of the remains of London's earliest-known Roman basilica, a massive public building that was the center of civic life in Londinium. Unearthed during the planning stages for a new skyscraper, this find has been hailed as one of the most significant in recent years. Similarly, excavations along the River Thames have uncovered new sections of the Roman riverside wall, a defensive structure that speaks to the strategic importance of Londinium. These discoveries are a direct result of the legal requirement for developers to fund archaeological investigations before construction, a practice that has made London a world leader in urban archaeology.

Mexico City: The Venice of the New WorldThe story of Mexico City is one of dramatic transformation. The modern city is built directly on top of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, a magnificent city of canals and floating gardens that was largely destroyed by the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century. For centuries, the remains of Tenochtitlan lay hidden beneath the colonial and modern city. However, a chance discovery by utility workers in 1978 led to the excavation of the Templo Mayor, the great temple of the Aztecs. Since then, a dedicated program of urban archaeology has continued to uncover the secrets of the Aztec capital. Excavations are often conducted in the most challenging of circumstances, squeezed between modern buildings, subway lines, and a high water table. Despite these difficulties, archaeologists have unearthed a wealth of artifacts, including sacrificial offerings, monumental sculptures like the Coyolxauhqui stone, and even the remains of an Aztec dwelling with its associated "chinampa" or floating garden. These discoveries provide a powerful connection to the pre-Hispanic past of one of the world's largest cities.

Istanbul: A Tale of Two EmpiresIstanbul's unique location, straddling Europe and Asia, has made it a prize for empires throughout history. The modern city encompasses the remains of both Byzantine Constantinople and the Ottoman capital. Like London, major infrastructure projects have provided opportunities for spectacular discoveries. The excavations for the Marmaray rail line and the Yenikapı metro station, for instance, unearthed the Theodosian Harbor, a Byzantine port filled with the wrecks of 37 ships, as well as a Neolithic settlement dating back 8,500 years. More recent excavations near the Hagia Sophia have revealed the remains of an Ottoman-era neighborhood built upon Byzantine foundations, a clear illustration of the city's layered history. The discovery of 1,500-year-old statues at the site of the Church of St. Polyeuktos further enriches our understanding of the artistic and cultural life of Byzantine Constantinople. These finds are a testament to the incredible density of history that lies just beneath the surface of this ancient city.

The Challenges and Complexities of Urban Geo-Archaeology

While the discoveries of urban geo-archaeology are often spectacular, the practice is fraught with challenges that go far beyond the technical difficulties of excavation.

The Race Against Time: Development vs. PreservationThe primary challenge for urban archaeology is the constant pressure of urban development. Archaeologists often have a very limited window of opportunity to investigate a site before it is destroyed by new construction. This creates a high-stakes environment where difficult decisions have to be made about what to excavate, what to document, and what to leave behind. The tension between the need for modern cities to grow and the desire to preserve their past is a constant balancing act.

Finding this balance requires a collaborative approach. Archaeologists must work closely with developers, architects, and city planners to integrate heritage preservation into the development process from the very beginning. Successful projects are often the result of productive working relationships where archaeology is not seen as an obstacle to development, but as an opportunity to add value to a project, creating a unique sense of place and connecting the new development to the city's deeper history.

Stakeholder Management: A Chorus of VoicesUrban archaeological projects involve a wide range of stakeholders, each with their own interests and concerns. These can include developers, government agencies, local communities, indigenous groups, and the general public. Navigating these often-competing interests requires a high degree of sensitivity and skill.

Community engagement is increasingly recognized as a crucial component of successful urban archaeology. By involving local residents in the process, archaeologists can foster a sense of ownership and pride in their local heritage. Community archaeology projects, where members of the public can participate in excavations and artifact processing, can be a powerful way to connect people to their past and build a constituency of support for heritage preservation. The Archeox project in East Oxford, for example, successfully engaged over 600 volunteers, uncovering significant new archaeological sites and fostering a lasting interest in the local history of the area.

The Preservation Paradox: In-Situ vs. Ex-SituOne of the most difficult questions in urban archaeology is what to do with the remains that are uncovered. Should they be preserved in-situ, left in their original location for the public to see? Or should they be excavated, documented, and then removed to make way for development?

In-situ preservation can be a powerful way to connect people to the past, creating "windows" into the buried city. However, it is often technically challenging and expensive. Exposed archaeological remains are vulnerable to weathering, pollution, and vandalism. Furthermore, integrating them into a new development requires careful planning and design.

Ex-situ preservation, on the other hand, allows for the complete documentation of a site and the recovery of artifacts for further study in a controlled environment. However, it also means the destruction of the site itself. The decision of whether to preserve in-situ or ex-situ is often a difficult one, with no easy answers. It requires a careful weighing of the significance of the remains, the feasibility of preservation, and the needs of the modern city.

The Future of Urban Geo-Archaeology: New Frontiers

As cities continue to grow and technology continues to evolve, the field of urban geo-archaeology is poised for even more exciting developments. The future of the discipline will likely be defined by a greater integration of technology, a more interdisciplinary approach, and a stronger emphasis on public engagement.

The Rise of AI and Big DataThe sheer volume of data generated by modern archaeological techniques presents a major challenge. From high-resolution geophysical surveys and 3D models to the vast archives of historical maps and documents, archaeologists are awash in information. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are emerging as powerful tools for analyzing these massive datasets. AI algorithms can be trained to automatically identify potential archaeological sites from satellite imagery, recognize patterns in artifact distributions, and even help to decipher ancient texts. Predictive modeling, which uses data on known archaeological sites and environmental factors to predict where new sites might be found, is becoming increasingly sophisticated with the use of machine learning. This can help to make archaeological fieldwork more efficient and targeted, a crucial advantage in the fast-paced world of urban development.

A More Interdisciplinary and Holistic ApproachThe future of urban archaeology will also be increasingly interdisciplinary. To fully understand the complex history of a city, archaeologists will need to collaborate more closely with historians, architects, urban planners, sociologists, and environmental scientists. This holistic approach will allow for a richer and more nuanced understanding of the forces that have shaped urban life over the centuries. By integrating archaeological data with historical records, architectural studies, and social analysis, we can move beyond the study of individual sites to a broader understanding of the city as a dynamic and evolving system.

The Power of Citizen ScienceThe future of urban geo-archaeology will also be more democratic. The rise of citizen science, facilitated by the internet and mobile technology, is providing new opportunities for the public to participate in archaeological research. Crowdsourcing platforms are being used to analyze satellite imagery for potential archaeological sites, transcribe historical documents, and even fund research projects. By engaging a wider audience in the process of discovery, citizen science can not only generate valuable new data but also build a stronger public appreciation for the importance of preserving our shared urban heritage.

Conclusion: The City as a Living Museum

The cities we inhabit today are not just collections of buildings and streets; they are living museums, each with a unique and complex history etched into its very foundations. Urban geo-archaeology provides us with the tools to read this history, to decode the stories of the ancient cities that lie just beneath our feet. It is a discipline that reminds us that the past is never truly past, but is an integral part of the present and a vital resource for shaping the future.

As our world becomes increasingly urbanized, the work of the urban geo-archaeologist will become more important than ever. By uncovering the successes and failures of past urban civilizations, we can learn valuable lessons about sustainability, resilience, and the enduring relationship between humanity and the urban environment. The next time you walk through the heart of a great city, remember that you are treading on layers of history, a silent city waiting to be rediscovered. And it is the urban geo-archaeologist, with their unique blend of scientific expertise and historical imagination, who will continue to bring its stories to light.

Reference:

- https://www.historica.org/blog/the-latest-ai-innovations-in-archaeology

- https://www.citizenscience.gov/catalog/432/

- https://www.ultralytics.com/blog/ai-in-archaeology-paves-the-way-for-new-discoveries

- https://skillfloor.com/blog/how-data-analytics-is-revolutionizing-archaeology

- https://student-journals.ucl.ac.uk/pia/article/id/197/print/

- https://group-cc.com/striking-a-balance-between-heritage-preservation-and-urban-regeneration/

- https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a12258-balancing-economic-development-and-heritage-preservation/

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/balancing-progress-and-heritage

- https://www.faithgpt.io/blog/using-ai-to-analyze-patterns-in-archaeological-data

- https://autogpt.net/the-role-of-ai-in-modern-archaeology/

- https://www.ailyze.com/blogs/ai-in-archaeology-qda-unearthing-historical-insights-in-2025

- https://ehhf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Ann-Degraeve_Speech.pdf

- https://www.quora.com/What-are-some-of-the-challenges-faced-by-archaeologists-when-excavating-historical-sites-in-urban-areas

- https://www.archidust.com/blog/2023/03/13/striking-a-balance-balancing-preservation-and-development-in-heritage-cities/

- https://www.mdpi.com/2571-9408/7/5/124

- https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/12/17/2795

- https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a13701-balancing-development-and-preservation-challenges-in-urban-heritage-conservation/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_archaeology

- https://www.una-europa.eu/knowledge-hub/toolkits/citizen-science-toolkit/discover-our-experts-citizen-science-projects

- https://urbanwaterslearningnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Urban-Arch-April-2017-1.pdf

- https://caracol.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Chase-and-Lobo-2024.pdf

- https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A2864525/view

- https://www.digitalmeetsculture.net/article/chnt22-urban-archaeology-and-integration/

- https://www.thepipettepen.com/conquer-pandemic-boredom-become-a-citizen-archaeologist-from-home-responsibly/

- https://www.socsci.ox.ac.uk/transformative-community-archaeology-project-breaks-new-ground

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307826863_Investing_in_Urban_Studies_to_Ensure_Urban_Archaeology's_Future_A_Response_to_'The_Challenges_and_Opportunities_for_Mega-infrastructure_Projects_and_Archaeology'

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/visit-urban-archeology.htm

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262206312_Integrating_new_digital_technology_into_the_humanities_3D_modeling_for_archaeology_art_history_and_urban_planning

- https://researchportal.helsinki.fi/en/publications/the-present-role-and-future-perspectives-of-urban-archaeology-in-

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259733435_Municipal_Archaeology_Programs_and_the_Creation_of_Community_Amenities

- https://www.studysmarter.co.uk/explanations/archaeology/conservation-and-preservation/conservation-challenges/

- https://durham-repository.worktribe.com/OutputFile/1648531

- https://libsearch.cbs.dk/discovery/fulldisplay/alma999900148305765/45KBDK_CBS:CBS

- https://publ.icomos.org/publicomos/jlbSai?html=Pag&page=Pml/Not&base=technica&ref=6AD0E4A292508810556BEE5D42D579FF

- https://www.saa.org/education-outreach/public-outreach/what-is-public-archaeology

- https://www.citizenheritage.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/CitizenHeritage-O1-July-2022.pdf

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7529236/

- https://www.mdpi.com/2220-9964/12/6/238

- https://matthewdharris.com/2016/11/23/archaeological-predictive-modeling-points-of-discussion/

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0239424

- https://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue70/6/index.html

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334703962_Chapter_3_Archaeology_as_a_conceptual_tool_in_urban_planning

- https://www.boston.gov/departments/archaeology/how-get-involved-city-archaeology