The World Before the Green Revolution

To comprehend the sheer scale of the Devonian Marine Revolution, one must first paint a picture of the world that preceded it. The Early to Middle Devonian period (roughly 419 to 383 million years ago) was a planet dominated by water. Two major supercontinents, Gondwana in the south and Euramerica (also known as Laurussia) straddling the equator, were surrounded by a vast global ocean. Sea levels were exceptionally high, creating shallow, warm, sunlit epicontinental seas that stretched for thousands of square miles across the continental crust. These seas were ideal incubators for life, fostering some of the most extensive and spectacular reef systems in Earth's history.

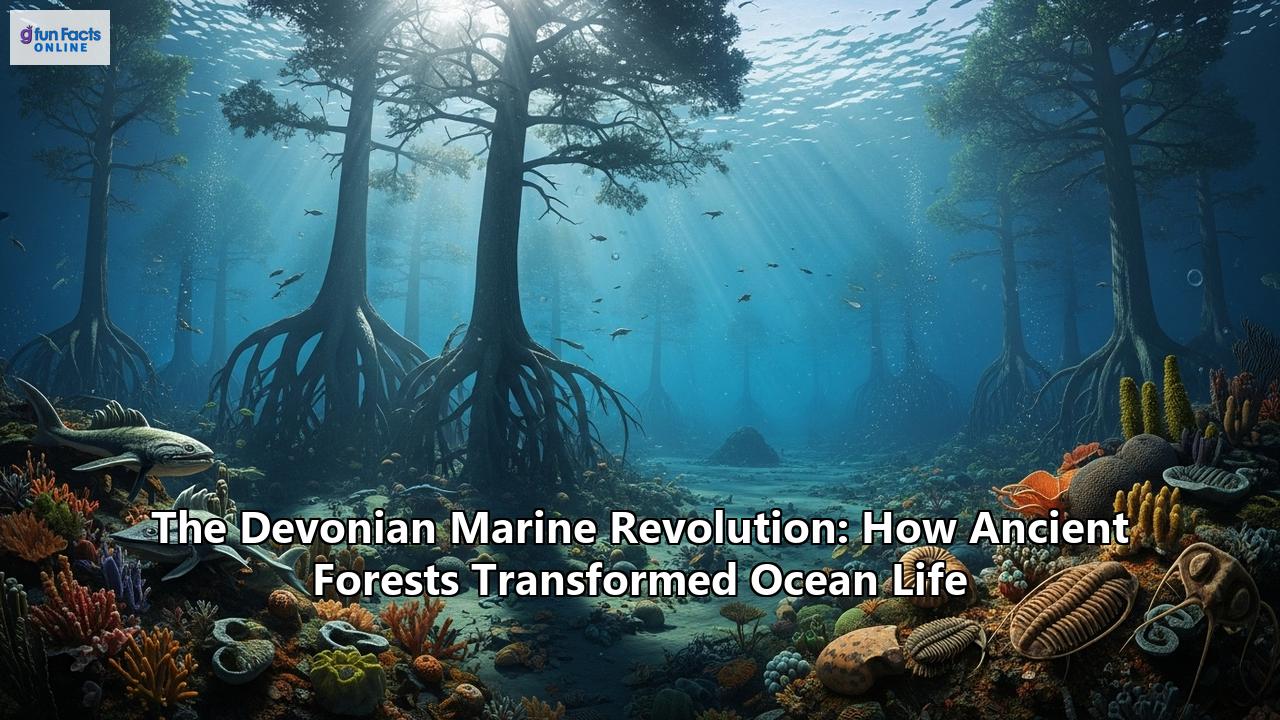

These were not the coral reefs we know today. The primary architects of these colossal structures were tabulate and rugose corals, alongside massive, mound-building organisms called stromatoporoids. These reefs, teeming with life, created complex, three-dimensional habitats. They were bustling metropolises of biodiversity, home to a staggering array of invertebrate life. Brachiopods, with their clam-like shells, were exceedingly common, filtering nutrients from the water. Trilobites, the iconic arthropods of the Paleozoic, scuttled across the seafloor in myriad forms. Crinoids, or "sea lilies," waved their feathery arms in the currents, while early ammonoids—coiled-shelled relatives of squid—began their long and successful evolutionary journey in the deeper waters.

The Devonian is famously nicknamed the "Age of Fishes," and for good reason. The vertebrates of the seas were undergoing a spectacular diversification. Armored, jawless fish known as ostracoderms, which had dominated in the previous Silurian period, were still common, grubbing for food in the sediment. But the great evolutionary innovation of the time was the jaw. This development triggered an explosion in vertebrate evolution. The placoderms, a diverse class of armored fish, rose to become the apex predators of their time. Some, like the formidable Dunkleosteus, grew to the size of a large shark, possessing not teeth, but horrifying, self-sharpening bony plates that could shear through almost any prey. Alongside them, the first cartilaginous fish (the ancestors of modern sharks) and bony fish (Osteichthyes) were becoming increasingly diverse, setting the stage for future dynasties.

Meanwhile, the land was a different world entirely. Compared to the vibrant oceans, the continents were relatively barren. Life had begun its conquest of the land, but it was a tentative occupation. During the preceding Silurian period, the first vascular plants, like Cooksonia, had appeared. These were tiny, simple organisms, rarely more than a few centimeters tall, with forking green stems ending in spore capsules. They lacked true roots, leaves, and the robust vascular tissue needed for height. They clung to the damp edges of rivers and lakes, forming little more than a green fuzz on the landscape. The soil beneath them was little more than broken rock and microbial mats, lacking the deep, organic-rich structure of modern soils. This was a world where the land was largely disconnected from the sea, a silent, static backdrop to the drama unfolding in the oceans. This fundamental separation was about to end, not with a gentle coupling, but with a planet-altering collision of ecosystems.

The Greening of the Continents: The Devonian Plant Explosion

The transition from a world of rock and scrub to one of towering forests was a key chapter in Earth's history, known as the Silurian-Devonian Terrestrial Revolution or the "Devonian Plant Explosion." This was not a single event, but a cascade of evolutionary innovations that unfolded over tens of millions of years, permanently rewiring the planet's systems.

The journey began with the small, waterside plants of the Early Devonian. While still primitive, they began to solve the fundamental problems of life on land. The evolution of vascular tissue—specialized tubes for transporting water and nutrients—allowed plants to grow taller and more complex. Genera like the lycophytes and trimerophytes reached heights of up to a meter, introducing a new, vertical dimension to terrestrial life.

A critical milestone was reached in the Middle Devonian (around 393 to 387 million years ago) with the appearance of the first true forests. Fossil evidence from sites in England reveals forests of cladoxylopsid trees, such as Calamophyton. These were strange-looking plants, with hollow, slender trunks and twig-like growths instead of broad leaves. Though they might appear alien to us, they represented a monumental step. They grew in dense stands, shed vast amounts of organic debris, and, crucially, began to develop more substantial root systems that stabilized the sediment, fundamentally altering how rivers flowed and landscapes formed.

However, the true game-changer was a group of plants called the progymnosperms, and specifically, the genus Archaeopteris. Appearing in the Late Devonian, Archaeopteris was arguably the first modern tree. It possessed a suite of advanced features that allowed it to outcompete other plants and colonize the globe. It had a strong, woody trunk, similar to that of a modern conifer, that could reach heights of 30 meters (nearly 100 feet). It had large, fern-like fronds that formed a dense canopy, shading out competitors. It even had lateral buds, allowing it to continue growing if its main shoot was damaged, a key trait for a long-lived perennial.

Most importantly, Archaeopteris developed the first truly extensive and deep root systems. Prior to this, plant rooting structures rarely penetrated more than 20 centimeters. Archaeopteris roots could drive more than a meter deep into the ground. This evolutionary leap had two profound consequences. First, it gave the tree a powerful anchor and the ability to tap into deeper water sources, freeing it from the wetlands and allowing it to conquer drier, inland floodplains. Archaeopteris rapidly spread, and by the end of the Devonian, it formed the backbone of the world's first global forests, from the tropics to near the Antarctic Circle.

The second consequence was even more significant: these deep, powerful root systems became engines of planetary change. They burrowed into the bedrock, breaking it apart physically. They also released acids and other compounds that dramatically accelerated the chemical weathering of rocks. This process, known as pedogenesis, began to create the world's first deep, complex soils. For the first time, a thick, organic-rich mantle containing a mixture of weathered rock minerals and decaying plant matter began to clothe the continents. This new soil layer held water, stabilized landscapes, and created new habitats. But in doing so, it also began to release a torrent of previously locked-away minerals and nutrients, unleashing them into the world's rivers and, ultimately, into the oceans. The greening of the land was about to trigger a crisis in the blue water.

The Poisoned Chalice: Nutrient Overload and Ocean Anoxia

The newly formed forests, which were transforming the land into a vibrant green world, were inadvertently brewing a toxic cocktail for the oceans. The same deep root systems that allowed Archaeopteris to thrive were also exceptionally efficient at mining the bedrock for nutrients essential for plant growth, most notably, phosphorus. As these vast forests expanded, and as generations of trees lived and died, this immense new reservoir of terrestrial biomass decayed, releasing unprecedented amounts of phosphorus and other nutrients into the river systems. This nutrient flood washed into the shallow epicontinental seas, triggering a process known as eutrophication—a deadly nutrient overdose.

In the sunlit surface waters, this sudden superabundance of nutrients was a spectacular boon for algae and other photosynthetic plankton. Their populations exploded into colossal, planet-spanning blooms. While this might seem like a positive development, it was the first step in a catastrophic chain reaction. As this massive quantity of plankton died, it sank into the deeper water layers. There, aerobic bacteria set to work decomposing the organic rain, and in doing so, they consumed enormous amounts of dissolved oxygen from the water column.

The scale of the organic fallout was so immense that it overwhelmed the ocean's ability to replenish its oxygen, leading to the formation of vast stretches of anoxic (low-oxygen) and even euxinic (anoxic and sulfidic) water. These "dead zones" would have suffocated most marine life that could not escape. Geochemical evidence written in the rock record confirms this scenario. Scientists studying Late Devonian sedimentary layers have found elevated levels of total phosphorus, indicating a massive nutrient influx. These layers are often black shales, rich in organic carbon that failed to decompose in the oxygen-starved environment. Furthermore, the analysis of uranium isotopes in these rocks provides a direct proxy for the extent of global marine anoxia, with data showing significant positive excursions that point to the widespread removal of oxygen from the oceans.

This process was not a single, continuous event but a series of devastating pulses. Two of these stand out in the geologic record as the primary culprits of the mass extinction: the Kellwasser and Hangenberg Events.

The Kellwasser Event, occurring at the boundary between the Frasnian and Famennian ages (around 372 million years ago), was a double-pulse of severe anoxia. Geochemical analysis of rock sections from this time shows clear evidence of widespread nutrient recycling on the sea shelf, where the low-oxygen conditions caused even more phosphorus to be released from the sediment, creating a vicious feedback loop that sustained and intensified the dead zones. This event was a hammer blow to the world's magnificent reef ecosystems. The stromatoporoids and corals, being stationary, shallow-water organisms, were unable to escape the suffocating, deoxygenated waters and were decimated.

Some 13 million years later, as the Devonian period drew to a close, the Hangenberg Event delivered the final blow (around 359 million years ago). This crisis was associated with a dramatic drop in sea level, followed by a rapid rise, which likely helped spread the anoxic waters across the remaining continental shelves. This event is also marked by elevated phosphorus levels, pointing again to terrestrial nutrient runoff as a key driver. The Hangenberg Event was particularly brutal for vertebrates, finishing off the already-struggling placoderms and nearly all remaining jawless fish.

A Perfect Storm: Compounding Crises

While the "Plants as the Trigger" hypothesis is a powerful and well-supported explanation for the Devonian marine crisis, the full picture is likely a complex interplay of multiple Earth-system shocks—a "perfect storm" of extinction. The relentless greening of the continents set the stage, but other dramatic events were unfolding at the same time, compounding the disaster.

The Volcanic Factor: Alongside evidence for anoxia, scientists have discovered another tell-tale chemical signature in the rocks of the Kellwasser event: sharp spikes in the concentration of mercury. On modern Earth, widespread mercury anomalies are a geochemical fingerprint of massive volcanic eruptions from Large Igneous Provinces (LIPs). While the specific volcanic provinces responsible are still being located, the evidence points to major eruptions in Siberia and a supervolcano in what is now Australia. These eruptions would have spewed immense quantities of greenhouse gases, toxic compounds, and aerosols into the atmosphere, directly stressing ecosystems. Some researchers now believe that all of the "Big Five" mass extinctions coincide with major volcanic events, and the Late Devonian is no longer seen as an exception. A leading theory is that the volcanic activity and the plant-driven nutrient crisis worked in tandem, with both needing to occur to push the Earth's systems past a tipping point into mass extinction. The Big Chill: Paradoxically, while volcanoes can cause short-term warming, the long-term effect of the new forests was global cooling. Plants are voracious consumers of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) for photosynthesis. As forests expanded across the globe, they acted as a planetary-scale carbon sink. Furthermore, the chemical weathering of silicate rocks, a process supercharged by the new deep-rooting systems, also draws down CO2 from the atmosphere.Evidence suggests that over the course of the Devonian, atmospheric CO2 levels may have plummeted from a greenhouse high of around 4,000 parts per million (ppm) to near-modern levels of 400 ppm. This dramatic reduction in greenhouse gases likely triggered a period of global cooling, and there is evidence for glaciation in the high-latitude regions of Gondwana toward the end of the Devonian. This cooling would have put immense stress on the tropical marine species, particularly the warm-water reef builders who were already suffering from anoxia. Rapid sea-level falls associated with the expansion of ice sheets would have exposed vast areas of the shallow continental shelf, destroying habitats and further contributing to the extinction.

Therefore, the Devonian Marine Revolution was not caused by a single culprit but by a devastating convergence of factors. The new forests loaded the gun by pumping nutrients into the sea and drawing CO2 from the atmosphere. Volcanic eruptions may have provided the initial trigger, causing short-term climate chaos. And the subsequent global cooling and glaciation added another layer of environmental stress. Caught in this crossfire, the once-stable and thriving marine ecosystems of the Devonian collapsed.

A New Marine World: The Winners and the Losers

Mass extinctions are not just about death; they are also about opportunity. By wiping the slate clean, they create ecological vacuums that surviving lineages can radiate into, fundamentally reshaping the tree of life. The Late Devonian extinctions were a profound evolutionary bottleneck that rerouted the course of marine history. The world that emerged in the subsequent Carboniferous Period was starkly different from the one that had preceded it.

The Losers: The devastation was most severe for the dominant, specialized, and often stationary life forms of the Devonian seas.- The Reef-Builders: The great stromatoporoid-coral reef systems were the single greatest casualty. These massive ecosystems, which had been a cornerstone of marine biodiversity for millions of years, were almost entirely wiped out. It would take over 100 million years, well into the Mesozoic Era, for coral reefs to recover to a similar global extent.

- Placoderms and Jawless Fish: The reign of the armored fish came to a definitive end. The diverse and fearsome placoderms, including the mighty Dunkleosteus, were completely eradicated by the Hangenberg Event. Most of the remaining agnathans (jawless fish) also vanished. Their extinction cleared the way for new vertebrate dynasties.

- Trilobites and Brachiopods: While they did not disappear entirely, these iconic Paleozoic groups were severely crippled. Trilobite diversity plummeted, and they never regained their former prominence, finally succumbing in the great Permian extinction millions of years later. Many families of brachiopods also went extinct, losing their dominance in shallow-water habitats.

- Sharks and their Kin (Chondrichthyes): While present in the Devonian, sharks were relatively minor players. The extinction of the placoderms opened up the niche of apex marine predator. Sharks and their relatives exploded in diversity and abundance, leading to the Carboniferous being dubbed the "Golden Age of Sharks." New and sometimes bizarre forms evolved, such as the stethacanthids with their strange, brush-like dorsal fins, and the petalodonts, flattened ray-like sharks.

- Ray-Finned Fishes (Actinopterygii): This group of bony fish, which includes the vast majority of modern fish species, were also beneficiaries of the extinction. They proved more resilient than their lobe-finned cousins and began a diversification that would eventually see them dominate marine and freshwater environments across the globe, a position they still hold today.

- Ammonoids: These coiled-shelled cephalopods were hit hard, with only a few lineages squeezing through the Hangenberg bottleneck. But from these few survivors, a new radiation began in the Early Carboniferous. They went on to become one of the most successful and diverse invertebrate groups of the Mesozoic Era, a classic example of post-extinction recovery.

The world that emerged from the Devonian extinctions was one where the old guards—the reef-builders and armored fish—were gone. The new world was one of swimmers and hunters, dominated by sharks and fast-moving bony fish. The very structure of the marine food web had been irrevocably altered. The revolution was complete.

The Enduring Legacy: A Modern Planet Forged in the Devonian

The series of events that transpired during the Devonian Period, from the rise of the first forests to the reconfiguration of ocean life, left a legacy that extends to the present day. This was not merely an ancient catastrophe; it was a formative era that established fundamental connections and systems that continue to govern our planet.

The most profound legacy is the permanent link forged between the terrestrial and marine biospheres. The evolution of deep-rooted forests meant that from the Devonian forward, the health of the oceans would be inextricably tied to the processes happening on land. The weathering of rock by roots, the creation of soil, and the subsequent runoff of nutrients became a permanent feature of the Earth system. This ancient crisis serves as a powerful paleo-analogue for modern environmental problems. The eutrophication and anoxia that devastated the Devonian seas are mirrored today in the "dead zones" that form in places like the Gulf of Mexico, where fertilizer runoff from agriculture creates the same nutrient-overload, algal bloom, and oxygen-depletion cycle. The Devonian teaches us that the land and sea are one interconnected system, a lesson of critical importance in the Anthropocene.

The "greening of the continents" had other lasting impacts. The deep, rich soils created by Archaeopteris and its successors changed Earth's surface forever, providing a stable and nutritious medium for all subsequent plant evolution. These soils also became massive carbon sinks, and the burial of organic matter from the vast swampy forests of the subsequent Carboniferous Period (which owed their existence to Devonian innovations) created the enormous coal seams that would one day fuel our own industrial revolution.

Furthermore, the drawdown of atmospheric CO2 by these first forests established a new climatic regime. While this contributed to the Devonian extinction through global cooling, it set the stage for the icehouse conditions of the Late Paleozoic and helped shape the climatic cycles that have governed Earth ever since.

Finally, the revolution in the seas was permanent. The extinction of the placoderms and the near-total collapse of the ancient reef systems created an evolutionary void that allowed for the rise of the modern vertebrate fauna. The sharks and ray-finned fishes that came to dominate the post-Devonian oceans are the direct ancestors of the groups that rule the seas today. The Hangenberg extinction event acted as an evolutionary bottleneck, pruning the tree of life in a way that directly shaped the roots of modern marine biodiversity.

In essence, the world we inhabit is a Devonian world. The soil under our feet, the composition of the air we breathe, the fish in the sea, and the delicate link between our forests and our oceans all have their roots in this turbulent and transformative period. The Devonian Marine Revolution was not just an extinction event; it was the crucible in which the modern Earth system was forged, a dramatic reminder that the greatest innovations on land can have revolutionary and unforeseen consequences in the sea.

Reference:

- https://scitechdaily.com/unraveling-earths-ancient-secrets-new-study-reshapes-understanding-of-devonian-era-mass-extinction/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236595012_The_ammonoid_faunal_change_near_the_Devonian-Carboniferous_boundary

- https://www.livescience.com/planet-earth/plants/plants-have-a-secret-second-set-of-roots-deep-underground-that-scientists-didnt-know-about

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Late_Devonian_mass_extinction

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/change/deeptime/devonian.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Mckye3w0GE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tournaisian

- https://ocean.si.edu/through-time/bony-beginnings-rise-vertebrate-innovation-devonian

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_fish_evolution

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351730761_Encyclopedia_of_Life_Sciences_eLS_Extinction_Late_Devonian_Mass_Extinction

- https://impact.ed.ac.uk/research/climate-environmental-crisis/how-soils-changed-life-on-earth/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ammonoidea

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolution_of_fish

- https://dcmurphy.com/devoniantimes/who/pages/archaeopteris.html

- http://palaeos.com/paleozoic/carboniferous/tournaisian.html

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329437641_GLOBAL_RESURGENCE_OF_CORAL-REEF_ECOSYSTEM_AFTER_THE_LATE_DEVONIAN_MASS_EXTINCTIONS

- https://news.uchicago.edu/story/study-finds-prehistoric-fish-extinction-paved-way-modern-vertebrates

- https://sites.google.com/site/paleoplant/geologic/phanerozoic/paleozoic/carboniferous/tournaisian

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeopteris

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/12/131213092841.htm

- https://cp.copernicus.org/articles/21/239/2025/

- https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/173763/1/1-s2.0-S0034666724001635-main.pdf

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2890420/

- https://library.fiveable.me/paleontology/unit-11/late-devonian-extinction/study-guide/9w2UASntKGzLWHqR

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/29827216_Mass_extinctions_climatic_and_oceanographic_changes_at_the_DevonianCarboniferous_boundary

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331661192_A_lungfish_survivor_of_the_end-Devonian_extinction_and_an_Early_Carboniferous_dipnoan_radiation

- https://www.britannica.com/science/Devonian-extinctions

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259475024_Ammonoid_evolution_in_Late_Famennian_and_Early_Tournaisian

- https://news.iu.edu/live/news/33770-study-reshapes-understanding-of-mass-extinction-in

- https://austhrutime.com/Chondrichthyan_late_palaeozoic_radiation.htm

- https://andrewblitman.com/2014/08/13/the-golden-age-of-sharks/

- http://www.elasmo-research.org/education/evolution/golden_age.htm

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338055810_Mid-Devonian_Archaeopteris_Roots_Signal_Revolutionary_Change_in_Earliest_Fossil_Forests

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carboniferous

- https://news.syr.edu/blog/2023/01/17/researchers-reject-30-year-old-paradigm-emergence-of-forests-did-not-reduce-co2-in-atmosphere/