Deep within the emerald embrace of the Malaysian rainforest, beneath a canopy that has filtered sunlight for millions of years, a silent heist is taking place. It is a robbery so sophisticated, so chemically complex, and so evolutionarily ancient that it happens entirely without motion. The perpetrator is not a creature of tooth and claw, nor an insect of venom and speed. It is a plant—but a plant unlike any that most of us would recognize. It has no green leaves to catch the sun, no towering stem to compete for the light. Instead, it is a ghostly, thumb-sized apparition that spends nearly its entire life buried underground, emerging only briefly to display a flower that looks less like a blossom and more like an alien artifact left by a miniature civilization.

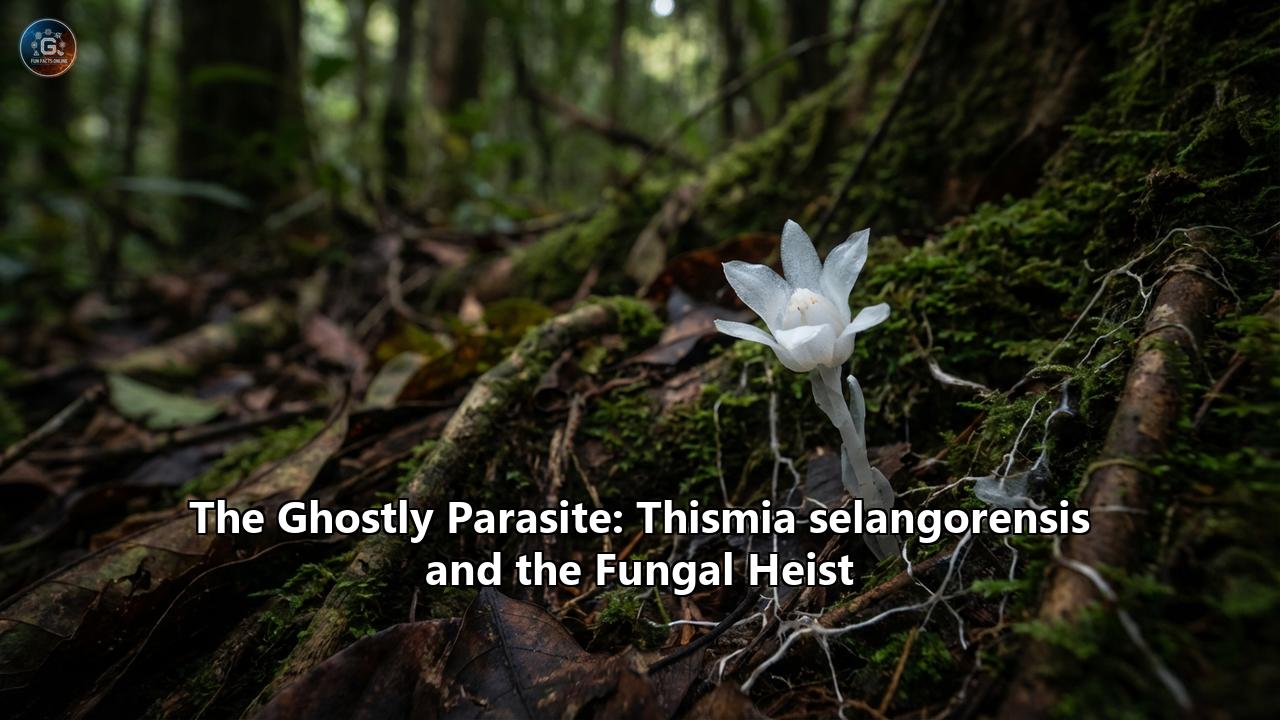

This is Thismia selangorensis, the Selangor Fairy Lantern.

Discovered only in late 2023 and described to science in 2024, this botanical enigma has quickly become a celebrity among botanists and a symbol of the fragility of our planet’s hidden biodiversity. It is a "mycoheterotroph"—a plant that has abandoned the hard work of photosynthesis in favor of a life of piracy. It taps into the vast, invisible fungal networks that pulse beneath the forest floor, stealing the energy harvested by towering trees nearby. It is a ghost in the machine of the rainforest, a beautiful parasite that challenges our very definition of what it means to be a plant.

This article delves deep into the world of Thismia selangorensis, exploring the detective story of its discovery, the intricate mechanics of its "fungal heist," the evolutionary journey that led it to the dark damp earth, and the desperate race to save it from extinction before we even fully understand its secrets.

Part I: The Discovery in the Shadows

The story of Thismia selangorensis does not begin in a remote, inaccessible jungle reachable only by helicopter or a week-long trek. It begins, ironically, at a picnic site.

The Unlikely SettingTaman Eko Rimba Sungai Chongkak is a popular recreational forest in the state of Selangor, Malaysia. It is a place where families go on weekends to escape the heat of Kuala Lumpur, to splash in the cool river waters, and to barbecue chicken under the shade of dipterocarp trees. It is a landscape of laughter, splashing water, and the smell of charcoal smoke—not the typical setting for the discovery of a species new to science.

Yet, biodiversity does not respect human boundaries. The rich, moist soil that lines the banks of the Chongkak River, shaded by the buttress roots of giant trees, provides a microhabitat of exceptional stability and humidity. It was here, in November 2023, that the sharp eyes of a naturalist named Tan Gim Siew spotted something unusual.

The "Eureka" MomentBotany in the tropics is often a game of scale. While the trees soar to forty or fifty meters, the most exciting discoveries are often taking place at the millimeter level in the leaf litter. Tan Gim Siew was scanning the ground near a tree buttress—a dark, sheltered niche often favored by fungi and small saprophytes—when a flash of color stood out against the decaying browns of the forest floor.

It was a small, fleshy flower, no taller than a finger, colored a delicate whitish-peach. It looked nothing like the surrounding vegetation. It had no green leaves, no woody stem. It looked, frankly, like a piece of coral or a strange mushroom that had lost its way.

Realizing the potential significance of the find, photographs were taken and shared with experts. The images eventually reached Siti-Munirah Mat Yunoh, a renowned botanist at the Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM) who has spearheaded the discovery of several Thismia species in recent years. To an expert eye, the plant was unmistakably a Thismia, a genus of rare plants known as "fairy lanterns" for their glass-like, intricate flowers. But it didn't match any known species.

The ConfirmationSubsequent expeditions were launched to the site. The researchers had to tread carefully—literally. The plants were so small and so well-camouflaged that a misplaced boot could wipe out a significant percentage of the known population. They found the plants growing in the moist leaf litter, often nestled in the "caves" formed by tree roots or in hollows near the riverbank.

Detailed morphological analysis followed. Under the microscope, the plant revealed its secrets. Its flower structure was unique. Unlike other Malaysian fairy lanterns, which might be orange or yellow with different ornamentation, this one had a specific "mitriform" (mitre-shaped) cap with three peculiar, club-shaped appendages rising like antennas. The internal structure of the flower, the arrangement of its stamens, and the texture of its floral tube were distinct enough to confirm it as a new species.

It was named Thismia selangorensis, honoring the state of Selangor where it was found. The discovery was a triumph, but it came with a sobering realization: the entire known population of this species consisted of fewer than 20 individuals, all confined to a single patch of forest smaller than a university campus.

Part II: The Ghostly Parasite

To understand why Thismia selangorensis is so special, one must look at what it lacks. It lacks chlorophyll, the green pigment that is the hallmark of the plant kingdom.

Abandoning the SunFor over a billion years, the evolutionary strategy of plants has been defined by photosynthesis. They use the energy of sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into sugars—food. This independence is what makes plants the "producers" of the food web. But photosynthesis is expensive. It requires building complex solar panels (leaves), maintaining rigid structures (stems and trunks) to hold those panels up to the light, and managing the water loss that comes with opening pores to let in carbon dioxide.

At some point in evolutionary history, the ancestors of Thismia took a different path. They found a shortcut. Instead of making their own food, they began to steal it.

The Anatomy of a Ghost Thismia selangorensis is a study in minimalism.- Leaves: Reduced to tiny, scale-like triangles along the stem. Since they don't need to catch light, they have atrophied into vestigial organs, pale and white.

- Stem: Short, fleshy, and white or pinkish. It has no need for wood or height. It only needs to be tall enough to lift the flower just above the rotting leaves so pollinators can find it.

- Roots: These are the business end of the operation. They are "coralliform," meaning they branch repeatedly like marine coral. This maximizes their surface area, not to absorb water from the soil, but to maximize contact with their fungal prey.

- The Flower: This is the only part of the plant that usually sees the light of day. In T. selangorensis, the flower is an architectural marvel. The "lantern" is actually a floral tube formed by fused petals. The top of the tube is covered by a "mitre," a roof-like structure that prevents rain from filling the cup. The three antenna-like appendages likely serve as chemical dispersers, wafting scent into the humid air to attract pollinators.

Part III: The Fungal Heist

The lifestyle of Thismia selangorensis is scientifically termed "mycoheterotrophy" (from Greek mykes = fungus, heteros = another, trophe = nutrition). In simpler terms: it eats fungi.

The Wood-Wide WebTo understand the heist, we must first understand the victim. The rainforest floor is underlain by a massive network of fungal threads called mycelium. These fungi are usually "mycorrhizal," meaning they live in a symbiotic relationship with the trees. The fungi colonize the tree roots, extending far into the soil to gather phosphorus, nitrogen, and water, which they trade to the tree. In return, the giant trees, bathing in the sunlight fifty meters above, pump sugars (carbon) down into the roots and feed the fungi. It is a fair trade: nutrients for sugar.

The Interception Thismia enters this relationship as a hacker. It inserts its roots into the soil, but instead of looking for water, it seeks out the fungal hyphae (threads) of the mycorrhizal network.When the fungal threads encounter the Thismia roots, they penetrate the plant's cells, likely expecting to establish a standard symbiotic trade. The fungus grows coils of hyphae, called pelotons, inside the Thismia root cells. This is where the trap springs.

In a normal plant, this interface would be a marketplace. In Thismia, it is a slaughterhouse.

Once the fungus has grown inside the Thismia cells, the plant activates a digestive mechanism. It releases enzymes that break down the fungal cell walls and digest the contents of the hyphae. The Thismia absorbs the carbon, nitrogen, and other nutrients that the fungus had painstakingly gathered from the soil or received from the trees.

The flow of energy is thus:Sun → Tree → Fungus → Thismia.

The tree photosynthesizes the sugar. The fungus receives the sugar from the tree. The Thismia eats the fungus. Therefore, Thismia selangorensis is indirectly parasitic on the surrounding trees, using the fungus as a bridge. It is the ultimate freeloader, stealing solar energy from the canopy without ever seeing the sun.

The Identity of the VictimWhile the specific fungal partner of T. selangorensis has likely not yet been sequenced due to its recent discovery, most Thismia species are specialists. They target Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF), specifically the phylum Glomeromycota. Research on related species like Thismia tentaculata has shown they can be incredibly picky, parasitizing only a single species of fungus.

This specificity is dangerous. If that one species of fungus dies out, or if the trees that support that fungus are cut down, the Thismia will starve. It binds the fate of the tiny fairy lantern to the health of the giant dipterocarp trees around it.

Part IV: The Fairy Lantern Family

Thismia selangorensis is not alone. It belongs to a genus of about 100 known species, collectively called "Fairy Lanterns." They are found in Asia, South America, Australia, and New Zealand, suggesting an ancient lineage that spread across the supercontinent Gondwana before it broke apart.

The "Geomitra" SectionTaxonomically, T. selangorensis is placed in the section Geomitra. This group of Thismia is characterized by flowers that look like mitres (the ceremonial headgear of bishops). Its closest relatives include:

- ---Thismia clavigera:--- A species found in Sarawak and Thailand, which also has appendages but differs in shape and color.

- ---Thismia malayana:--- Another recently discovered Malaysian species, described in 2024, which has a darker, brownish-purple coloration and lacks the specific antenna-like projections of selangorensis.

- ---Thismia neptunis:--- perhaps the most famous relative, rediscovered in Borneo in 2017 after being lost for 151 years. It looks like a bizarre alien mouth facing the sky.

Each of these species represents a slight variation on the same theme: how to build a flower that attracts pollinators in the dark, damp understory without spending too much energy.

Evolutionary OdditiesThe evolution of Thismia is a story of reduction. Over millions of years, they lost the genes for photosynthesis (the rbcL gene and others in the chloroplast genome are often missing or non-functional). They lost their stomata (air pores). They lost their ability to regulate water transport like normal plants.

In exchange, they gained complexity in their flowers. Because they don't need light, they can grow in the deepest shade where competition is low. Because they don't need to build leaves, they can live as tiny tubers for years, waiting for the perfect moment to flower. They are masters of efficiency, existing as pure potential energy underground until the rains come.

Part V: The Ecosystem of Taman Eko Rimba

To fully appreciate Thismia selangorensis, we must appreciate its home. The Taman Eko Rimba Sungai Chongkak is a dipterocarp lowland forest. This is one of the oldest and most complex ecosystems on Earth.

The Canopy and the FloorAbove, the giants of the forest—species of Shorea and Dipterocarpus—dominate the skyline. They are the "sugar daddies" of the ecosystem, pumping carbon into the soil. Below them, the understory is a tangle of rattans, palms, and gingers.

But down in the leaf litter, where Thismia lives, the world is different. It is a world of decomposition. Bacteria, fungi, termites, and beetles are constantly breaking down the rain of dead leaves from above. This creates a nutrient-rich, humid layer of soil called "humus."

The River's EdgeThismia selangorensis seems to prefer the riparian zone—the area of land immediately adjacent to the river. The soil here is constantly moist, which is crucial for a plant that has little control over its own water retention. The flooding of the river also deposits fresh silt and nutrients, keeping the fungal networks vigorous.

However, this reliance on the riverbank is also its greatest vulnerability.

Part VI: Critically Endangered

When a species is discovered with fewer than 20 individuals in a single location, the celebration is instantly mixed with anxiety. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) uses strict criteria to assess extinction risk. Thismia selangorensis fits the criteria for Critically Endangered (CR) almost perfectly.

The Threats- Hyper-Endemism: As far as we know, this plant exists nowhere else on Earth. A single landslide, a severe flood, or a disease outbreak could wipe out the entire species in a week.

- Trampling: The plant grows right next to picnic areas and hiking trails. It is small, brown, and blends into the leaves. A tourist looking for a spot to set up a camping chair could unknowingly crush the last flowering individual of the species.

- Habitat Alteration: If the park decides to widen a path, build a new gazebo, or clear "brush" to make the area look tidier, the Thismia would be destroyed.

- Poaching: Unfortunately, the rarity of "fairy lanterns" makes them targets for specialized collectors. While Thismia are almost impossible to cultivate (because you can't easily grow the specific fungus and the tree it needs), this doesn't stop people from digging them up.

How do you conserve a plant you can't see for 11 months of the year? You can't fence off every patch of soil. You can't dig them up and move them to a botanical garden, because they will die without their fungal web.

The only way to save Thismia selangorensis is to protect the habitat itself. This means leaving the leaf litter undisturbed. It means educating the park staff and the public. It means treating the messy, rotting floor of the forest as a sacred space, just as vital as the towering trees above.

Part VII: Why It Matters

One might ask: Why does it matter if a tiny, leafless parasite goes extinct? It doesn't provide timber. It doesn't cure cancer (as far as we know). It doesn't feed the birds.

But Thismia selangorensis matters because it is a bio-indicator. Its presence tells us that the forest soil is healthy. It tells us that the mycorrhizal networks are intact. It tells us that the connection between the trees and the fungi is functioning. It is the tip of the iceberg, the visible sign of the immense, hidden complexity of the rainforest.

Furthermore, its specialized lifestyle pushes the boundaries of biological science. Studying how Thismia steals carbon without triggering the fungus's immune system could teach us about plant defense and parasitism. Studying its genes could teach us about how genomes evolve when they stop needing to photosynthesize.

And on a more philosophical level, Thismia selangorensis represents the wonder of the unknown. In a world where we think we have mapped every corner and named every beast, the fact that a strange, alien-looking flower can hide in plain sight at a popular picnic spot is a reminder of how much we still have to learn.

Conclusion: The Lantern in the Dark

The Selangor Fairy Lantern is a paradox. It is a parasite, yet it is beautiful. It is locally abundant in its tiny patch, yet globally on the brink of extinction. It is a thief, yet it is a masterpiece of evolution.

As the monsoon rains fall on the canopy of Taman Eko Rimba Sungai Chongkak, the water trickles down the trunks of the great trees, soaks into the humus, and wakes up the sleeping tubers of Thismia selangorensis. Slowly, silently, the white stems push up through the rotting leaves. The intricate mitres unfold. The antennas rise.

For a few days, the forest floor is lit by these ghostly lanterns. They signal the presence of a hidden world, a complex web of life that connects the tallest tree to the smallest fungus. And then, as quickly as they appeared, they dissolve back into the earth, waiting for the next rain, and hoping that the boots of the giants—us—will tread lightly enough to let them rise again.

Reference:

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/a-rare-parasitic-fairy-lantern-plant-species-was-discovered-in-malaysia-it-might-be-critically-endangered-180987941/

- https://indiandefencereview.com/rare-fairy-lantern-species-malaysia-facing-extinction/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fSlM6YjofVY

- http://novataxa.blogspot.com/2025/12/thismia.html

- https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2021-06-29-botanists-name-astonishing-new-species-fairy-lantern-malaysian-rainforests

- https://botany.one/2019/06/thismia-and-its-unusual-number-of-specialist-relationships/

- https://www.mdpi.com/2673-6500/4/4/41

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12680943/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thismia

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.793876/full