The New Iron Age: How Modular Green Smelting is Rewriting the Rules of Heavy Industry

Introduction: The Rust on the MachineFor over three thousand years, the basic recipe for making iron has remained remarkably unchanged: take iron-rich rock, mix it with a carbon-heavy fuel (charcoal, then coal, then coke), and blast it with intense heat to strip away the oxygen. This alchemical violence, known as smelting, built the modern world. It forged the skeletons of our skyscrapers, the hulls of our ships, and the chassis of our cars. But this foundation comes with a staggering cost. The traditional blast furnace is a beast that breathes fire and exhales poison. Today, the steel industry is responsible for approximately 7% to 9% of all global carbon dioxide emissions—a footprint larger than that of the entire nation of India.

If the steel industry were a country, its carbon emissions would rank it third in the world, behind only China and the United States. For decades, this was accepted as the unavoidable price of progress. Steel is the most used metal on Earth; we simply couldn't exist without it. But a quiet revolution is dismantling this assumption. It is not happening in the sooty, sprawling mega-complexes of the 20th century, but in compact, high-tech modules that look more like server farms than foundries.

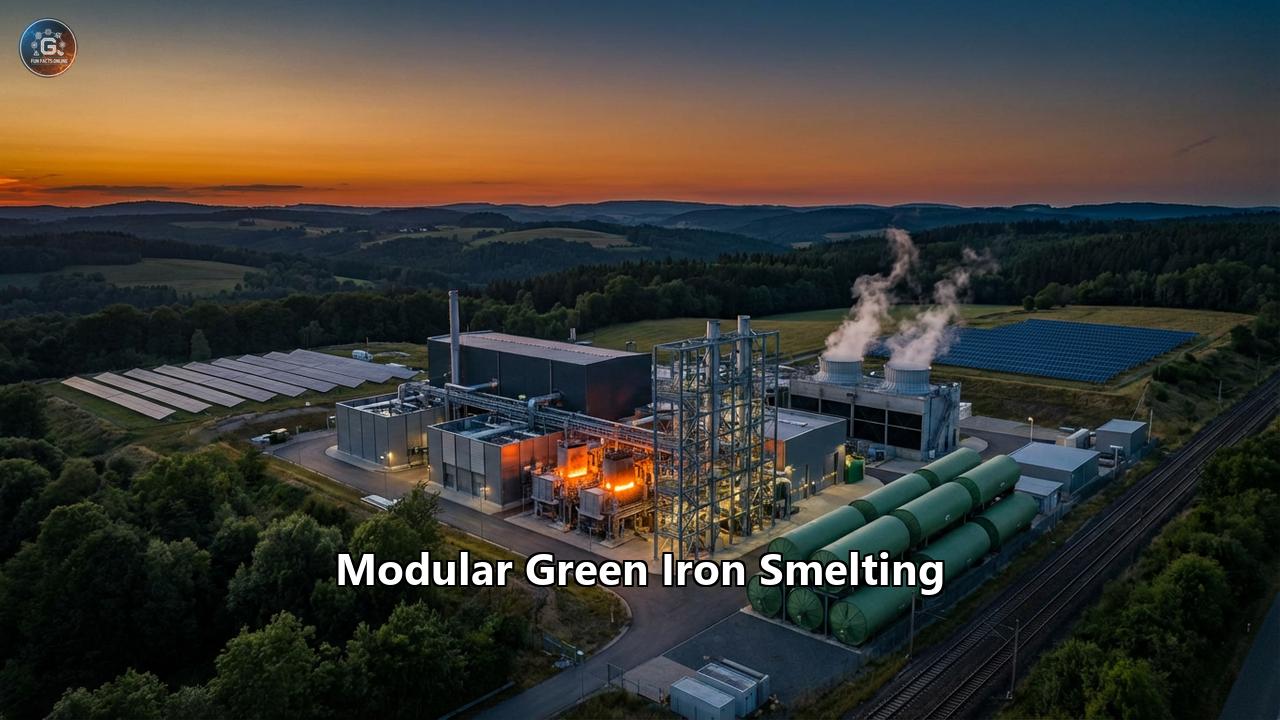

Welcome to the era of Modular Green Iron Smelting. This is not just a tweak to an old process; it is a fundamental unbundling of the industrial supply chain. It promises to decouple ironmaking from steelmaking, move heavy industry from coal-rich regions to sun-drenched deserts, and democratize the production of the world’s most critical material.

Chapter 1: The Monolith vs. The ModuleTo understand the radical nature of modular green iron, we must first understand the "Monolith"—the integrated steel mill.

A traditional integrated steelworks is a marvel of logistical brute force. It requires massive infrastructure: deep-water ports to receive coal and ore, coke ovens to bake coal, sinter plants to prepare ore, and the blast furnace itself—a cathedral of fire that, once lit, cannot be turned off for 15 to 20 years without incurring millions of dollars in damage. These facilities cost billions to build and require decades to pay off. They rely on the "economies of scale" principle: the bigger the furnace, the cheaper the steel.

The Modular DisruptionModular green iron smelting flips this logic on its head. Instead of a single, billion-dollar furnace that demands constant feeding, modular technologies use small, standardized units that can be combined like Lego bricks.

- Scalability: A company can start with ten modules and scale to a hundred as demand grows. This lowers the "barrier to entry" from billions of dollars to millions.

- Flexibility: Modules can be turned up, down, or off to match the fluctuating supply of renewable energy (wind and solar), solving one of the biggest challenges of green electrification.

- Portability: These units are often designed to be truck-transportable. This means ironmaking can move from the industrial rust belts to the source of the iron ore itself—remote mines in Australia, Brazil, or Africa—effectively "exporting sunshine" in the form of green iron.

Three distinct technologies are vying for the throne of this new era. Each offers a different path to the same goal: stripping oxygen from iron ore without using carbon.

1. The Hydrogen Vanguard (H2-DRI)- The Concept: This is the most mature technology. Instead of using carbon monoxide from coal to strip oxygen from iron ore, it uses green hydrogen (H2). The byproduct is not CO2, but H2O—pure water vapor. The result is Direct Reduced Iron (DRI), a porous, metallic "sponge iron."

- The Modular Angle: While companies like Stegra (formerly H2 Green Steel) are building massive plants, the technology is shrinking. Startups and established players like Midrex are designing flexible, smaller-scale shaft furnaces that can run on varying mixtures of hydrogen.

- The Challenge: It requires high-grade iron ore. Impurities in lower-grade ore can clog the electric arc furnaces (EAFs) that eventually melt this iron into steel.

- The Player: Boston Metal, an MIT spinoff, is the poster child for this approach.

- The Tech: Think of it as a battery in reverse. An electrical current is passed through a liquid bath of iron ore. The electricity zaps the chemical bonds holding the iron and oxygen together. Oxygen bubbles off as a gas, and pure molten iron pools at the bottom.

- The "Bus" Factor: Boston Metal’s reactor cells are roughly the size of a school bus. They don’t need a massive complex. You can line up 100 of them in a warehouse. If one breaks, you pull it offline and fix it while the others keep humming. Crucially, MOE can handle low-grade iron ores that H2-DRI cannot, potentially unlocking billions of tons of previously "useless" ore.

- The Players: Companies like Electra and Element Zero.

- The Tech: These systems operate at drastically lower temperatures (around 60°C to 100°C, compared to 1,600°C for traditional smelting). They dissolve iron ore in an acid or alkaline solution and plate out pure iron on an electrode, similar to how copper is refined.

- The Advantage: Because they run at low temperatures, they can easily ramp up and down, making them the perfect partner for intermittent wind and solar power. They essentially act as a "grid battery" that produces iron plates instead of stored charge.

Perhaps the most profound impact of modular smelting is not chemical, but geographical. For two centuries, iron ore has traveled to the coal.

- Australia ships rocks to China.

- Brazil ships rocks to Japan.

- The ore is heavy, but the coal was the energy source, so the industry clustered around energy hubs.

In the new model, iron travels to the sunshine.

It makes little economic sense to ship green hydrogen; it is a fluffy, low-density gas that is nightmare to transport. It is far cheaper to generate the hydrogen (or electricity) right next to the iron mine, smelt the ore into "Green Iron Briquettes" (HBI), and ship that.

- Shipping Economics: Shipping HBI (Hot Briquetted Iron) saves roughly 75% of the transport volume compared to shipping the equivalent hydrogen and iron ore separately.

- The New Map: This creates "Green Iron Hubs" in places like the Pilbara (Australia), the Middle East, Namibia, and Brazil. These regions become the new "Saudi Arabias of Steel," exporting high-value green metal instead of cheap raw rocks.

- The Consumer: Traditional steelmakers in Europe or Japan (like ArcelorMittal or Nippon Steel) stop being "ironmakers." They shut down their dirty blast furnaces and become "melters," buying green iron briquettes from abroad and melting them in electric furnaces to make car bodies and beams. They move up the value chain, leaving the energy-intensive heavy lifting to the renewable-rich south.

"Green Steel" has long carried a "Green Premium"—a higher cost that scared away buyers. But the economics are shifting rapidly due to the modular advantage.

1. CAPEX vs. OPEX- Old Way: Invest $2 billion. Wait 5 years for construction. Hope the market is good in 2030.

- Modular Way: Invest $50 million. Build a pilot plant in 12 months. Start generating revenue. Reinvest profits to add more modules. This lowers the cost of capital and reduces risk, attracting venture capital and tech investors who would never touch a traditional steel mill.

- Renewable energy is now the cheapest form of power in history in sunny/windy locations.

- Modular plants that can "load follow" (ramp up when sun shines, down when it sets) can utilize "spilled" or excess renewable energy that would otherwise be wasted, driving electricity costs toward zero.

- Europe's CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism): Effectively a carbon tariff. If you try to sell dirty steel into Europe, you will pay a penalty. This creates an immediate price premium for green iron.

- USA's IRA (Inflation Reduction Act): Offers massive subsidies for green hydrogen production (up to $3/kg), which acts as rocket fuel for H2-DRI projects in the States.

The path is not without potholes.

- The Green Hydrogen Bottleneck: We need massive amounts of electrolyzers to make enough hydrogen. The supply chain for electrolyzers is currently stretched thin.

- Grid Infrastructure: Even modular plants need grid connections. In remote mining areas, building the high-voltage transmission lines to connect solar farms to smelters is a logistical hurdle.

- The "Grade" War: As mentioned, H2-DRI needs high-grade ore (67% iron content or higher). The world is running out of this "direct shipping ore." This forces a race between finding new high-grade mines (like Simandou in Guinea) and perfecting technologies (like Boston Metal's MOE) that can eat low-grade dirt.

Modular Green Iron Smelting is more than a cleanup operation for a dirty industry. It is a redistribution of global industrial power. It offers developing nations in the "Global South" a chance to industrialize without carbonizing, turning their natural blessings of sun, wind, and ore into high-value exports.

For the first time in history, a steel mill doesn't need to be a monolith that darkens the sky. It can be a clean, quiet collection of modules sitting in the desert, silently turning red dust into the green metal that will build our future. The Iron Age isn't ending; it's just getting an upgrade.

Reference:

- https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/energysource/clean-industrial-policies-a-space-for-eu-us-collaboration/

- https://steelwatch.org/steelwatch-explainers/steelwatch-explainer-why-green-iron-trade-will-catalyse-steel-industry-decarbonisation/

- https://ieefa.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/Australia%20faces%20growing%20green%20iron%20competition%20from%20overseas_Sep23.pdf

- https://discoveryalert.com.au/hydrogen-based-ironmaking-technology-2025-decarbonisation/

- https://usclimatealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/USClimateAlliance_Guide_IndustrialDecarbonizationStatePolicyGuidebook_2022.pdf

- https://greenh2catapult.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/green_iron_corridors_steel_supply_chain_report.pdf

- https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/green-iron-opportunities-in-australia_bbd1e2b8-en/full-report/component-5.html

- https://steelwatch.org/press-releases/importing-green-iron-saves-75-of-transport-capacity-needs-compared-to-separate-hydrogen-and-iron-ore-shipments/

- https://files.core.ac.uk/download/pdf/35142217.pdf

- https://fiia.fi/en/publication/us-eu-climate-change-industrial-policy