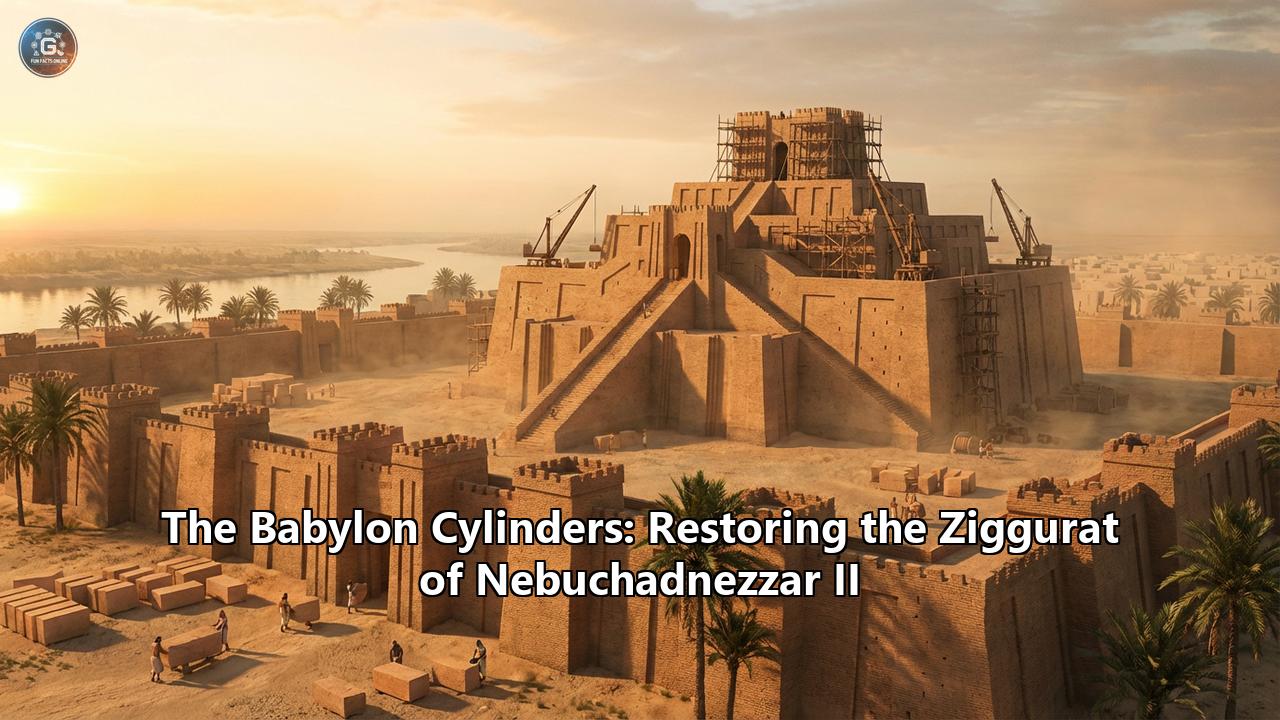

In the flat, sun-baked plains of Mesopotamia, roughly 90 kilometers south of modern-day Baghdad, lies a waterlogged depression in the earth. To the untrained eye, it is nothing more than a muddy square, choked with reeds and surrounded by the broken debris of history. But to the archaeologist and the historian, this square is the "ground zero" of human ambition. It is the footprint of the Etemenanki—the "Temple of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth." It is the ghost of the Ziggurat of Babylon. It is, in all probability, the historical reality behind the biblical Tower of Babel.

For centuries, the Etemenanki was a creature of myth. It existed in the indignant verses of Genesis, where humanity’s hubris was punished with the confusion of tongues. It existed in the fantastical accounts of Herodotus, who described a tower of eight solid layers stacked like a wedding cake, spiraled by a ramp. But for the last century, and particularly in light of recent discoveries, the tower has moved from myth to tangible history.

Central to this resurrection are the voices of the builders themselves. Buried deep within the mudbrick foundations of the great Mesopotamian cities were the "time capsules" of the ancient world: the Foundation Cylinders. These barrel-shaped clay artifacts, inscribed with the intricate wedges of cuneiform script, were never meant for human eyes. They were messages written by kings to the gods, buried in the dark earth to certify that a ruler had performed his sacred duty.

Among the most significant of these are the cylinders and steles of Nebuchadnezzar II, the great Neo-Babylonian king who reigned from 605 to 562 BCE. Through these texts—some known for decades, others analyzed only recently—we can now reconstruct the story of the Great Ziggurat not as a fable of divine punishment, but as a triumph of engineering, logistics, and religious devotion. We can now "read" the restoration of the tower in the king's own words, hearing the voice of a man who looked at a ruin and resolved to make it rival the stars.

Part I: The Voice in the ClayThe foundation cylinder is a uniquely Mesopotamian phenomenon. While Egyptian pharaohs carved their boasts onto towering stone obelisks for all to see, Babylonian kings were more concerned with the audience below the earth (the netherworld deities) and the audience of the future (kings who would one day dig up their ruins).

The cylinders relevant to the Etemenanki are masterpieces of propaganda and piety. They are typically made of fine clay, fired to a buff or greenish hardness that has allowed them to survive 2,500 years in damp soil. The script is often tiny, requiring a magnifying glass to read, yet executed with calligraphic precision.

One of the most famous excerpts comes from a cylinder found in the ruins of Babylon, now held in collections like the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In it, Nebuchadnezzar speaks directly about the ziggurat:

"Etemenanki, the Ziggurat of Babylon, of which Nabopolassar, the king of Babylon, my father, had fixed the foundation, but had not raised its top to the heavens. I set my hand to build it. I made it the wonder of the people of the world. I raised its top to heaven, made doors for the gates, and I covered it with bitumen and bricks."

This is not the lament of a confused builder; it is the project report of a successful one. The inscriptions reveal that Nebuchadnezzar did not build the tower from scratch. He was the restorer. The tower was ancient even in his time, a holy relic that had fallen into disrepair. His father, Nabopolassar, had begun the work, clearing the debris and laying the new foundation mantle, but he had died before the "head" of the tower could be raised.

The "Tower of Babel Stele"While the cylinders provide the text, a spectacular artifact from the Schøyen Collection, known as the "Tower of Babel Stele," provides the visual. Discovered in the late 20th century, this black stone monument features the only known contemporary depiction of the Etemenanki.

On the stele, we see Nebuchadnezzar himself. He is depicted standing tall, wearing the conical royal hat, holding a staff in one hand and plans—or perhaps a foundation nail—in the other. Facing him is the Great Ziggurat. It is not a spiral minaret as shown in medieval European paintings. It is a stark, stepped pyramid with seven distinct stages, culminating in a high temple at the summit.

The inscription on this stele is thrillingly specific. Nebuchadnezzar boasts:

"I mobilized all countries everywhere, each and every ruler who had been raised to prominence over all the people of the world... The base I filled in to make a high terrace. I built their structures with bitumen and baked brick throughout. I completed it raising its top to the heaven, making it gleam bright as the sun."

The reference to "mobilizing all countries" and "people of the world" offers a fascinating historical echo of the Biblical "confusion of tongues." Babylon was a metropolis of deportees. Jews, Assyrians, Syrians, Elamites, and Egyptians were all present in the city, many as forced laborers. A construction site of this magnitude would indeed have been a cacophony of different languages—Aramaic, Akkadian, Hebrew, Egyptian—making the "Babel" legend a poetic interpretation of a sociological reality.

Part II: The Architecture of AweWhat exactly was Nebuchadnezzar restoring? Based on the cylinders, the stele, and the famous "Esagila Tablet" (a later copy of a Neo-Babylonian dimension text), we can reconstruct the Etemenanki with high accuracy.

The DimensionsThe base was a perfect square, measuring roughly 91 meters (300 feet) on each side. The height, according to the texts, was equal to the width—another 91 meters. For context, this is roughly the height of a 30-story modern building, an unimaginable skyscraper in a world of single-story mud huts.

The StructureThe core of the ziggurat was made of sun-dried mudbrick—millions upon millions of them. This was the traditional building material of Mesopotamia, but it had a fatal flaw: it dissolved in rain. A ziggurat with an exposed mud core would eventually melt into a shapeless mound (which is exactly what the Etemenanki is today).

Nebuchadnezzar’s great innovation—or rather, his extravagant application of technology—was the "baked brick mantle." He encased the soft mud core in a shell of kiln-fired bricks, which were as hard as stone and impervious to water. These bricks were not just stacked; they were bonded with bitumen (asphalt), a natural tar that bubbled up from the ground in Iraq. This bitumen mortar was waterproof and flexible, allowing the massive structure to settle without cracking.

The Bible remembers this engineering detail with surprising accuracy: "And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime [bitumen] had they for mortar." (Genesis 11:3).

The Seven StagesThe tower rose in seven stages. The first stage was a massive block, 33 meters high. Above that, five smaller platforms stacked up like stairs. The seventh and final stage was the Sahuru—the High Temple.

The cylinders describe this summit in lavish terms. It was plated with "blue glazed bricks," likely meant to blend with the sky, making the tower appear to connect physically with the heavens. The roof beams were made of cedar imported from Lebanon, covered in gold and silver. At the corners, bronze bulls or dragons stood guard.

This was not a tomb, like the Egyptian pyramids. It was a machine. It was a "stairway to heaven," designed not for humans to go up, but for the god Marduk to come down. The High Temple at the top was a bedchamber for the god, containing a massive couch and a golden table, awaiting his visitation.

Part III: The King Who BuiltTo understand the restoration, one must understand the restorer. Nebuchadnezzar II is often villainized in Judeo-Christian tradition as the destroyer of Jerusalem and the enslaver of the Jews. But in his own cylinders, he presents a different face: the pious architect.

Nebuchadnezzar was obsessed with legitimacy. His father, Nabopolassar, had been a usurper who helped destroy the Assyrian Empire. Nebuchadnezzar needed to prove that he was the true, divinely appointed heir to the ancient traditions of Babylon.

Restoring the Etemenanki was the ultimate act of piety. The ziggurat had been destroyed by the Assyrian king Sennacherib in 689 BCE in an act of calculated sacrilege. Sennacherib had not just knocked it down; he had dumped the debris into the canals to erase it from the earth. By rebuilding it, Nebuchadnezzar was healing a national wound. He was proclaiming that the Assyrian age of chaos was over and the Babylonian Golden Age had begun.

The "Project Manager" KingThe cylinders reveal Nebuchadnezzar as a micromanager. He didn't just order the tower built; he claims to have participated.

"I fashioned mattocks, spades, and brick-moulds from ivory, ebony, and musukkannu-wood, and set them in the hands of a vast workforce... I myself carried the basket on my head."

While the image of the king carrying a basket of wet clay is ceremonial—a ritual trope of Mesopotamian kingship—it underscores the importance of the work. The "basket-carrier" icon was a symbol of the king as the servant of the gods. The cylinders found at Kish in early 2026, which describe his restoration of the ziggurat there, reinforce this image. They show a king who traveled from city to city—Babylon, Borsippa, Kish, Ur—assessing the structural integrity of ancient temples ("its walls had buckled," "rain had carried away its brickwork") and authorizing vast resources to fix them.

Part IV: The Context of the CityThe restored Ziggurat did not stand in isolation. It was the anchor of a vast urban plan that Nebuchadnezzar executed to make Babylon the center of the world.

If you were a visitor to Babylon in 570 BCE, the Etemenanki would have dominated your view from miles away, a blue-tipped mountain rising from the plains. As you approached the city, you would pass through the Ishtar Gate, a towering double-gate facade covered in lapis-lazuli blue glazed bricks adorned with golden dragons (symbols of Marduk) and bulls (symbols of Adad).

Passing through the gate, you would walk down the Processional Way, a paved avenue flanked by walls decorated with 120 lions (symbols of Ishtar) striding alongside you. This road was designed for the gods. During the Akitu (New Year) festival, the statues of the gods were carried along this path.

The Processional Way ran parallel to the massive enclosure of the Etemenanki. The ziggurat sat inside a vast courtyard, surrounded by administrative buildings, storerooms, and priests' quarters. To the south lay the Esagila, the ground-level temple of Marduk, a sprawling complex of shrines and altars. The Ziggurat and the Esagila were a pair: the "Low Temple" for the daily worship of the people and priests, and the "High Temple" for the celestial communion of the god.

The Wet Pit and the "Bitumen Flood"One of the most evocative details in the cylinders is the description of the foundation work. The water table in Babylon has always been high. To build a tower that wouldn't sink, the engineers had to dig deep. Nebuchadnezzar describes using "asphalt and bitumen like a mighty flood."

Archaeological evidence bears this out. Excavations have shown that the entire precinct was raised and paved. The amount of bitumen used was astronomical. It was floated down the Euphrates from Hit (modern-day Anbar province). The smell of hot tar, the smoke of the brick kilns, and the dust of crushed gypsum would have filled the air of Babylon for decades.

Part V: The Fall and the AftermathThe tragedy of the Etemenanki is how short-lived its glory was. Nebuchadnezzar finished his great work around 570 BCE. Babylon fell to the Persians under Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE—less than 40 years later.

Initially, the Persian kings respected the ziggurat. Cyrus and his son Cambyses may have performed rituals there. But as Babylon rebelled against Persian rule, the city’s fortifications and symbols of power were targeted. By the time Herodotus allegedly visited (c. 450 BCE), the tower was still standing, but perhaps already showing signs of neglect.

The death blow came not from an enemy, but from time and structural failure, followed by a failed rescue attempt. When Alexander the Great conquered Babylon in 331 BCE, he was mesmerized by the ancient city. He wanted to make it the capital of his new empire. He saw the Etemenanki, now crumbling, and decided to restore it to its Nebuchadnezzar-era glory.

However, the Greek engineers realized that the rubbish and debris from the eroding superstructure were so vast that they couldn't simply patch it. They decided to dismantle it completely to build it anew. Alexander conscripted 10,000 men to tear the ziggurat down to its foundations.

They succeeded in the demolition. But before the reconstruction could begin, Alexander died in Nebuchadnezzar’s palace in 323 BCE.

The empire fractured. The project was abandoned. The great "Tower of Babel" was left as a flat, leveled foundation—a void in the landscape. Over the ensuing centuries, the baked bricks were carted away by locals to build houses, and the mud core dissolved back into the swamp.

Part VI: The Modern ResurrectionFor two millennia, the location of the tower was lost. Early travelers mistook the nearby ruins of Borsippa (the Ziggurat of Nabu, which was vitrified by heat and remained standing) for the Tower of Babel.

It was not until the German excavations led by Robert Koldewey in 1913 that the true Etemenanki was found. Koldewey located the square footprint, the "wet pit," and fragments of the triple staircase described in the texts. He also found the scattered bricks stamped with Nebuchadnezzar’s name.

Today, the site remains a challenge. The high water table—the same enemy Nebuchadnezzar fought with bitumen—makes excavation difficult. But the cylinders have allowed us to bypass the mud. We don't need to dig up the tower to see it; we can build it in our minds using the blueprints left by the king.

The "Kish" Connection: A 2026 DiscoveryThe story of the cylinders is not over. In early 2026, archaeologists announced the translation of new foundation cylinders found at the site of Kish, a sister city to Babylon. These cylinders, also from Nebuchadnezzar II, describe the restoration of the Ziggurat of Kish (dedicated to the war god Zababa).

These new texts are crucial because they confirm the consistency of Nebuchadnezzar’s program. The language is nearly identical to the Babylon cylinders: the lament over the ruin, the divine command to rebuild, the pride in the "shining" result. They confirm that the restoration of the Etemenanki was not a vanity project, but part of a systematic, empire-wide policy of religious revival. Nebuchadnezzar was trying to "reset" the clock of Mesopotamian history, anchoring his new empire in the deepest bedrock of the past.

Conclusion: The Enduring SignalThe Babylon Cylinders are more than just clay receipts. They are the voice of a civilization asserting its place in the cosmos. When we read Nebuchadnezzar’s words—"I raised its top to heaven"—we are reading the historical kernel of the Babel myth.

The irony, of course, is that the Bible was right, but for the wrong reasons. The builders did make a name for themselves that has lasted forever. They did build a tower that reached the heavens, not physically, but culturally. Through the preservation of these clay cylinders, the Ziggurat of Babylon has outlasted its own destruction. The bricks may be gone, scattered into the hovels of Hilla or dissolved into the Iraqi mud, but the idea of the tower—the "Structure of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth"—stands inviolate in the text.

Nebuchadnezzar II failed to build a tower that would last forever. But by writing his story in clay, he built a memory that the waters of the Euphrates could never wash away.

Glossary of Key Terms

- Etemenanki: Sumerian for "Temple of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth." The proper name of the Ziggurat of Babylon.

- Ziggurat: A stepped pyramidal tower characteristic of major Mesopotamian cities.

- Esagila: The "Low Temple" of Marduk located near the ziggurat, the center of daily worship.

- Marduk: The patron god of Babylon and the head of the Babylonian pantheon.

- Bitumen: A natural asphalt used as mortar and waterproofing agent.

- Cuneiform: The wedge-shaped writing system of ancient Mesopotamia.

- Koldewey, Robert: The German archaeologist who excavated Babylon (1899-1917) and identified the foundations of the Etemenanki.

- Schøyen Collection: A private collection of manuscripts that holds the "Tower of Babel Stele."

Timeline of the Etemenanki

- c. 1700s BCE: Possible original construction (Hammurabi era).

- 689 BCE: Destroyed by Sennacherib of Assyria.

- c. 650 BCE: Partial restoration begun by Esarhaddon.

- c. 605-562 BCE: The Great Restoration by Nebuchadnezzar II (The era of the Cylinders).

- 539 BCE: Babylon falls to Persia; Ziggurat remains standing.

- 331 BCE: Alexander the Great conquers Babylon.

- 323 BCE: Alexander demolishes the tower to rebuild it, but dies. The project is abandoned.

- 1913 CE: Rediscovered by Robert Koldewey.

- 2026 CE: New cylinders from Kish shed light on Nebuchadnezzar's building program.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Etemenanki

- https://www.schoyencollection.com/history-collection-introduction/babylonian-history-collection/tower-babel-stele-ms-2063

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/321676

- https://alongthesilkroad.com/2025/10/07/the-tempel-of-the-foundation-of-heaven-and-earth-the-etemenanki/

- https://www.archaeology.wiki/blog/2011/12/29/the-tower-of-babel-king-nebuchadnezzar-ii-and-the-sch%C3%B8yen-collection/

- https://grokipedia.com/page/Etemenanki

- https://madainproject.com/tower_of_babel_stele

- https://www.livius.org/articles/place/babylon/etemenanki/

- https://www.kchanson.com/ANCDOCS/meso/nabo.html

- https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3019&context=ocj

- https://api.repository.cam.ac.uk/server/api/core/bitstreams/77b2c5db-900a-4f70-b297-cf8eafac8c1e/content

- https://www.quantumgaze.com/ancient-history/representation-tower-babel-stele/