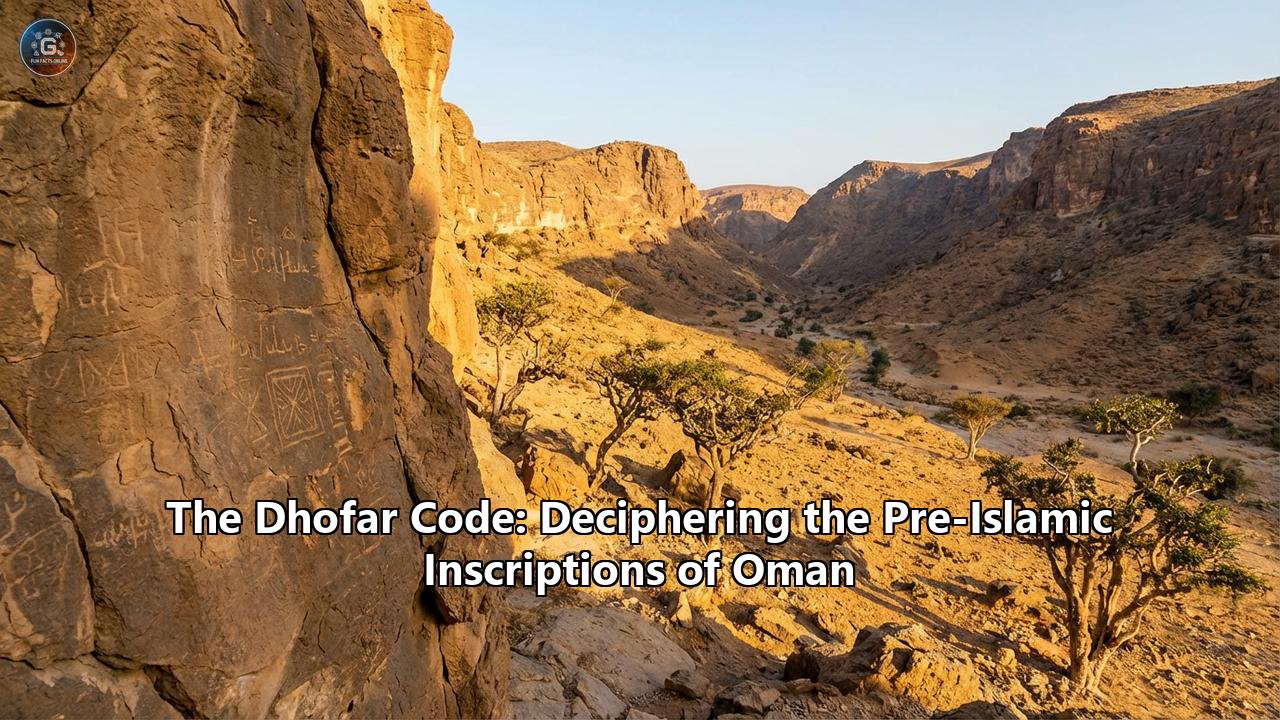

The air in Wadi Darbat is heavy with moisture, a stark contrast to the arid vastness of the Arabian Peninsula that stretches endlessly to the north. Here, in the Dhofar region of southern Oman, the monsoon—known locally as the Khareef—performs an annual miracle, turning the limestone cliffs emerald green and feeding the waterfalls that cascade into turquoise pools. For centuries, this mist-shrouded landscape has guarded a secret. etched in red pigment on the walls of caves and carved into the boulders of dry riverbeds.

For over a hundred years, scholars and travelers stood before these markings, baffled. They saw snake-like squiggles, geometric diamonds, and trident shapes that defied translation. They were clearly a script, but they belonged to no known alphabet. In the absence of science, myth rushed in to fill the void. Locals whispered that these were the writings of the ’Ad, the colossal giants mentioned in the Quran who built the pillared city of Iram before being destroyed by a divine wind. The inscriptions became a "Dhofar Code," a silent testament to a lost civilization that had seemingly vanished without a whisper.

But the silence has finally been broken. In a landmark breakthrough in late 2025, the code was cracked. We now know that these texts are not the work of mythical giants, but the intimate, prayerful, and mundane voices of the ancestors of the people who still walk these valleys today.

This is the story of that decipherment, the ancient world it revealed, and the enduring legacy of Oman’s unique linguistic heritage.

Part I: The Ghost of the 'Ad

To understand the magnitude of the decipherment, one must first understand the shadow that hung over these inscriptions for so long. Dhofar is not just a geological anomaly; it is a place steeped in folklore. The Quran speaks of the tribe of 'Ad, a powerful civilization of "stature and power" to whom the prophet Hud was sent. They were said to have built "Iram of the Pillars," a city of unmatched splendor, only to be buried by the sands for their hubris.

For generations, the Bedouin of Dhofar and the Jibbali (mountain) people looked at the strange, painted characters in the caves of Wadi Darbat and the caves of the Nejd plateau and saw the handwriting of the 'Ad. The script was unlike the majestic Musnad—the monumental South Arabian script found on the temples of Yemen and in the ruins of Sumhuram nearby. Musnad was the script of kings and incense merchants, geometric and orderly. The Dhofar script, by contrast, was fluid, often painted, and chaotic. It looked like the scratching of a people who lived apart.

Western explorers who arrived in the 19th and early 20th centuries, like Bertram Thomas and Wilfred Thesiger, noted these "curious characters" but could make no headway in reading them. They were cataloged simply as "graffiti," a dismissive term that belied their importance. As the search for the "lost city of Ubar" intensified in the 1990s—culminating in the discovery of the site at Shisr—the mystery of the script deepened. Was this the language of Ubar? Was it a cipher used by the frankincense caravans to hide their trade secrets?

Without a "Rosetta Stone"—a bilingual text comparing the unknown script to a known one—the Dhofar Code remained unbreakable. It sat in the "undeciphered" column of human history, alongside the Indus Valley script and Linear A.

Part II: The Breakthrough

The turning point came not from digging in the dirt, but from looking at the patterns of the letters themselves. In 2025, Ahmad Al-Jallad, a philologist and epigrapher renowned for his work on the languages of pre-Islamic Arabia, turned his attention to high-resolution photographs of the Dhofar inscriptions documented years earlier by researchers like Ali Maḥāsh al-Shahri and Geraldine King.

The problem with deciphering short texts—and most Dhofar inscriptions are very short—is that there isn't enough data to find statistical patterns. If you see a three-letter word, it could be "dog," "god," "cat," or a name. However, Al-Jallad noticed something peculiar in a few longer inscriptions found in the deep interior.

These texts didn't look like sentences. They consisted of a string of signs that did not repeat. In the world of epigraphy, a non-repeating sequence of unique signs usually means one thing: an abecedary.

An abecedary is simply the alphabet written out in order—A, B, C, D... Ancient scribes used them to practice, just as children do today. Al-Jallad realized that if he was looking at the Dhofar alphabet in its fixed order, he could compare it to the fixed orders of other known Semitic alphabets.

The ancient Semitic world had two main "orders" for their alphabets:

- The Abjad Order: (A-B-G-D...) which gives us the word "Abjad" and is the ancestor of our A-B-C-D order.

- The Halḥam Order: (H-L-Ḥ-M...) This was the order used by the Ancient South Arabians in Yemen.

When Al-Jallad tested the Dhofar signs against these sequences, the lock clicked open. The "snake" sign aligned with the position of Lam (L). The "trident" aligned with H. The script followed the southern Halḥam order, but the letter shapes themselves were not South Arabian Musnad. They were a distinct, independent evolution—a "missing link" in the history of the alphabet.

With the phonetic values of the letters established, the "gibberish" on the cave walls suddenly transformed into sound. The first word to emerge from the darkness was not a magical incantation or a king's decree. It was a relationship.

brIn many Semitic languages, bin or ben means "son of." But in the Modern South Arabian languages spoken in Dhofar today, the word is ber or bar. The inscriptions were full of the word br.

Ḥayb br Mys — "Ḥayb son of Mys." ’Akay br Thabn — "’Akay son of Thabn."The code was broken. The "Giants" were actually fathers, sons, and daughters.

Part III: The Voice of the Ancestors

What does a lost civilization have to say after 2,000 years of silence? The content of the Dhofar inscriptions, now that we can read them, is profoundly human. They are not the boastful propaganda of emperors. They are the personal expressions of a pastoral people living in a dangerous and beautiful world.

Protective Invocations:Many inscriptions are prayers found at the entrances of caves or near water sources. They call upon deities for protection (s-t-r). They ask for safety from predators, perhaps the Arabian leopard or the wolf, which still roam these mountains. One touching inscription simply reads, hĝf-h, meaning "Help him!"—a cry across the centuries from someone in distress.

Names and Lineage:The obsession with genealogy is a hallmark of Arabian tribal society, and the Dhofar texts are no different. Men and women carved their names to mark their presence. "I am [Name], son of [Father], of the lineage of [Tribe]." These names allow us to reconstruct the social web of ancient Dhofar. We see family clusters returning to the same caves season after season, likely following the grazing patterns of their camels and goats.

The "Paint" vs. The "Chisel":One of the most striking features of the Dhofar script is that it was often painted. Using red ochre and animal fat, these ancient scribes created a calligraphy that is unique in the peninsula. While the rest of Arabia was hammering crude graffiti into hard basalt, the Dhofaris were painting flowing, cursive-like symbols on limestone. This suggests a culture that valued the visual aesthetic of writing. It implies that there were likely perishable materials—palm leaves or leather—that they wrote on, which have long since rotted away, leaving only the cave paintings as the surviving "hard drives" of their culture.

Part IV: The Linguistic Fossil – A Living Heritage

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the Dhofar Code is not that it is dead, but that it is, in a way, still alive.

For decades, linguists have studied the Modern South Arabian Languages (MSAL). These are six small languages spoken in Oman and Yemen: Mehri, Shehri (also called Jibbali), Harsusi, Hobyot, Bathari, and Soqotri.

Crucially, these are not dialects of Arabic. They are independent Semitic languages, as different from Arabic as French is from Spanish. They retain ancient sounds (like the lateralized "dad" sound) that Arabic lost over a thousand years ago. When Al-Jallad deciphered the Dhofar script, the language that emerged was clearly an ancestor or a close aunt of these modern languages.

For the speakers of Mehri and Shehri, this discovery is a vindication. They have long maintained that they are the indigenous people of this land, with a history pre-dating the arrival of northern Arab tribes. The inscriptions prove them right. When a modern Shehri speaker says ber for "son," he is using the exact same word his ancestor painted on a cave wall in Wadi Darbat 2,000 years ago.

The Dhofar script is the "missing body" to the "living soul" of the MSAL languages. It shows that these tribes were not illiterate nomads on the fringe of history; they had a literacy of their own, independent of the powerful Sabaean kingdoms to the west (Yemen) and the Arab kingdoms to the north.

Part V: The Land of Frankincense

We cannot separate the script from the land. The people who wrote these texts were living in the epicenter of one of the most important trade networks in human history: the Frankincense Route.

The Boswellia sacra tree, which bleeds the aromatic white resin when cut, grows only in this specific microclimate. In the ancient world, frankincense was more valuable than gold. It was burned in the temples of Rome, Jerusalem, and Babylon to carry prayers to the gods. It was used to mask the stench of burning bodies in funeral pyres and to treat everything from toothaches to indigestion.

The writers of the Dhofar inscriptions were the harvesters of this "white gold."

Imagine the scene: A shepherd in the high plateau of the Nejd, watching his herd grazing among the gnarled frankincense trees. He takes a break in the shade of a limestone overhang. He mixes a bit of red pigment and paints his name and a prayer for rain. Below him, down the precipitous escarpment, caravans are loading the resin onto camels to trek across the Empty Quarter to the Mediterranean. To the south, at the port of Sumhuram (Khor Rori), ships are setting sail for India.

The inscriptions reveal that while the trade was international, the harvesters were locals. They lived a life distinct from the cosmopolitan merchants in the coastal cities. The coastal cities like Sumhuram used the "international" script of the time (Musnad) for their official receipts and temple dedications. But up in the hills, in the caves, the people stuck to their own script—the Dhofar script. It was a mark of identity, a way of saying, "We are the people of the mountains."

Part VI: The "Atlantis of the Sands" Revisited

The decipherment also forces us to re-evaluate the legends of Ubar. In the 1990s, when the site of Shisr was identified as a potential candidate for the legendary city, headlines screamed about the "Atlantis of the Sands."

The Dhofar inscriptions found near Shisr and other trade outposts do not reveal a magical city of giants. Instead, they reveal a pragmatic network of water management and tribal alliances. The "pillars" of Iram might well have been the wooden supports of the trade structures or the limestone formations of the caves themselves.

The reality is perhaps more impressive than the myth. The survival of these people in such a harsh environment—managing water resources, harvesting resin, and maintaining a distinct cultural identity for millennia—is a feat of human resilience. The "Giants" of Dhofar were not physical giants; they were giants of survival.

Part VII: A New Chapter for Omani Heritage

For the Sultanate of Oman, the deciphering of the Dhofar Code is a cultural milestone. It places Dhofar on the map not just as a source of raw resources (frankincense), but as a center of intellectual production.

This discovery is leading to a renaissance in Omani archaeology.

- Conservation: The painted caves, previously vulnerable to touch and vandalism by tourists who didn't understand their value, are now being recognized as open-air archives. Steps are being taken to protect the pigments which have survived for 2,000 years but could disappear in a decade of careless tourism.

- Education: There is a push to integrate this history into Omani textbooks. Children in Salalah can now learn that their ancestors had their own alphabet.

- Language Revitalization: For the endangered Modern South Arabian languages, this is a lifeline. Seeing their language in an ancient script gives young speakers a sense of pride and historical weight, countering the pressure to shift entirely to Arabic.

Conclusion: The Message on the Wall

In a quiet cave in Wadi Darbat, there is a small inscription that roughly translates to "Grant safety to [Name] and his camels."

It is a simple request. But deciphering it has collapsed the distance between us and the past. We no longer see a mysterious, alien symbol. We see a man, worried about his livelihood, looking up at the sky, and leaving a mark of his hope.

The Dhofar Code has not revealed the location of hidden gold or magical technology. It has revealed something far more valuable: the humanity of the pre-Islamic past. It has given a voice back to the shepherds, the mothers, and the frankincense harvesters who walked these wadis long before the modern world arrived.

The mists of the Khareef will continue to roll over the Dhofar mountains, turning the brown earth to green. But now, when we look at the red marks on the cave walls, we will not see a mystery. We will see a greeting.

Author's Note: The decipherment of the Dhofar script is a developing field. As more inscriptions are found and analyzed, our understanding of this ancient language will continue to grow, further illuminating the rich tapestry of human history in the Arabian Peninsula.