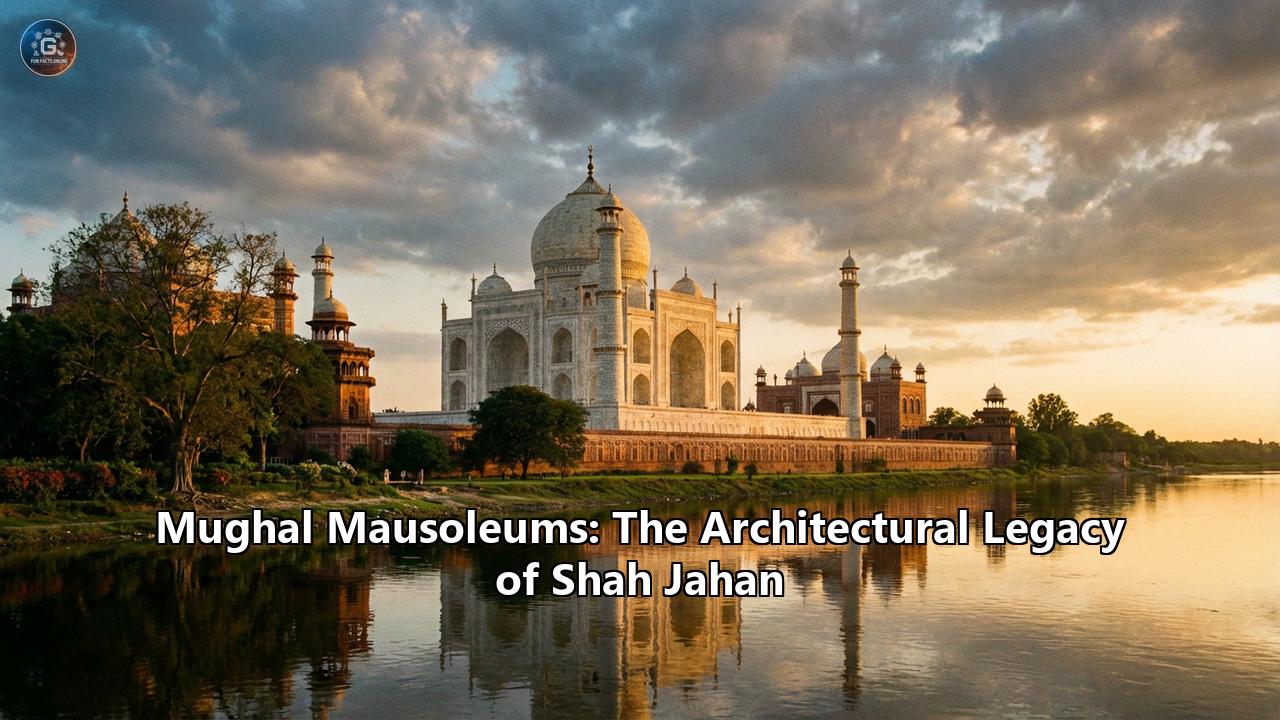

The river Yamuna, sluggish and dark, winds its way through the plains of northern India, a silent witness to the rise and fall of empires. Yet, upon its banks, rising like a mirage from the dust of history, stands a legacy written not in ink, but in white marble and red sandstone—a legacy of symmetry, theology, and an almost obsession with perfection. This is the architectural inheritance of the fifth Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan. While his grandfather Akbar built an empire of swords and alliances, and his father Jahangir cultivated an empire of art and nature, Shah Jahan sought to build an empire of stone that would outlast time itself.

The era of Shah Jahan (1628–1658) is universally recognized as the Golden Age of Mughal architecture. It was a period where the robust, eclectic style of Akbar—which fused Hindu beams with Persian domes—gave way to a more refined, orthodox, and lyrically feminine aesthetic. The sandstone turned to marble; the sturdy lintel curved into the foliated arch; and the simple geometric carving blossomed into the hyper-realistic floral sprays of parchin kari (pietra dura).

To understand this legacy, one cannot simply look at the Taj Mahal, though it is the sun around which all other monuments orbit. One must journey from the dusty plains of Agra to the riverbanks of Lahore, exploring the "forgotten" tombs, the experimental laboratories of design, and the philosophical underpinnings that turned a mausoleum into a map of Paradise. This comprehensive exploration will dissect the engineering marvels, the artistic triumphs, and the human stories embedded within the Mughal mausoleums of the Shah Jahan era.

Chapter 1: The Imperial Canvas – A Shift in Stone

To appreciate the revolution Shah Jahan brought, one must first understand what came before. When Babur, the first Mughal, arrived in India, he complained bitterly of the heat, the dust, and the lack of running water. His contribution was the Charbagh—the four-quartered garden—a geometric imposition of order upon the chaotic Indian landscape. Akbar, the empire-builder, used architecture as a political tool. His buildings at Fatehpur Sikri were muscular and red, carved from the local sandstone, blending Islamic domes with Rajput chhatris (kiosks) and brackets. They were monuments of integration.

Shah Jahan, however, was different. Born Prince Khurram, he was arguably the most "Indian" of the Mughals by blood up to that point, yet his architectural taste veered sharply back toward the Persianate and Timurid roots of his dynasty, albeit refined through an Indo-Islamic lens.

Upon ascending the throne in 1628, his treasury was overflowing. The empire was secure. He did not need to project strength through jagged stone; he wanted to project divinity through polished surfaces. His reign marked the "Age of Marble." In the Red Fort of Agra, he tore down many of Akbar’s red sandstone structures and replaced them with white marble pavilions like the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience).

This shift was not merely aesthetic; it was symbolic. In ancient Hindu treatises (Shilpa Shastras), white stone was often reserved for Brahmins and the divine, while red was for the Kshatriyas (warriors). By wrapping his imperial structures and, eventually, his mausoleums in white marble, Shah Jahan was subtly elevating the Mughal Padishah from a warrior-king to a semi-divine figure, the "Shadow of God on Earth" (Zill-e-Ilahi).

Chapter 2: The Architect and the Vision

No great building exists without a great mind behind it. While Shah Jahan was the visionary patron, deeply involved in the design process, the technical genius is often attributed to Ustad Ahmad Lahori.

Lahori was not just a mason; he was a mathematician, an astronomer, and a master engineer. Hailing from a family of architects with roots in Herat (modern-day Afghanistan), Lahori held the title Nadir-ul-Asar ("Wonder of the Age"). His genius lay in his ability to translate the Emperor's theological concepts into structural reality.

The challenge facing Lahori and his team was immense. The Mughals wanted to build massive domes, but the Indian plains offered soft, alluvial soil. To build the heavy monuments we see today near riverbanks, they had to invent a new kind of foundation. They utilized deep wells (chah) lined with timber and filled with rubble and mortar. These wells acted like the piles of a modern skyscraper, anchoring the structure deep into the water table. It is a supreme irony of history that the Yamuna River, which threatens the Taj Mahal today with its drying bed, was the very thing that kept the timber foundations moist and strong for centuries.

Chapter 3: The Crown Jewel – The Taj Mahal

The narrative of Mughal mausoleums inevitably centers on the Taj Mahal, but to treat it only as a "monument to love" is to ignore its architectural profundity. Completed in 1648 (with the complex finished in 1653), it is the physical manifestation of the Islamic concept of Jannat (Paradise).

The Great Gate (Darwaza-i-Rauza)

The experience of the Taj Mahal is choreographed. One does not simply stumble upon the tomb. One must pass through the Darwaza-i-Rauza, a monumental gateway built of red sandstone. This structure serves as a transition zone—a veil between the chaotic, material world of the bazaar (Taj Ganj) and the spiritual serenity of the garden. The gate is lined with calligraphic inscriptions from the Quran, specifically Surah Al-Fajr (The Dawn), inviting the "soul at peace" to enter the garden of the Lord.

A masterstroke of optical illusion is employed here. As you approach the gate, the Taj Mahal, framed within the arch, appears immense. As you walk through the gate, the monument appears to shrink, as if pulling away, creating a sensation of awe and unreachability.

The Garden (Charbagh)

In previous Mughal tombs, like Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, the mausoleum sat in the exact center of the Charbagh. Shah Jahan broke this rule. He placed the Taj Mahal at the far end of the garden, perched on a raised plinth overlooking the river.

Why? There are two theories.

- Aesthetic: By placing the white mountain of marble against the backdrop of the sky rather than the garden, the silhouette is uninterrupted.

- Theological: The river Yamuna was incorporated into the design as one of the rivers of Paradise. The garden, with its four water channels, represents the rivers of water, milk, wine, and honey promised in scripture.

The planting within the garden was equally symbolic. Cypress trees (representing death and mourning) were planted alongside fruit trees (representing life and renewal), creating a living allegory of the cycle of the soul.

The Main Mausoleum

The structure itself is a marvel of symmetry. It sits on a square plinth of marble, 95 meters on each side. The four minarets, each over 40 meters tall, frame the tomb. Ustad Ahmad Lahori incorporated a subtle fail-safe: the minarets tilt slightly outward. To the naked eye, they look straight, but this tilt ensures that in the event of a massive earthquake, the towers would fall away from the central dome, sparing the tomb.

The dome is the crowning glory. Unlike the lower, hemispherical domes of early Islamic architecture, this is a "bulbous" or "onion" dome, a shape perfected in the Timurid architecture of Central Asia (like the Gur-e-Amir in Samarkand). It sits on a high drum, raising it toward the heavens. It is a double-dome structure—a false ceiling inside creates a proportionate interior scale, while the outer shell rises high for exterior grandeur. The acoustic properties of this hollow space are legendary; a single note sung inside the cenotaph chamber reverberates for several seconds, a sonic metaphor for the lingering voice of God.

Chapter 4: The Art of Parchin Kari (Pietra Dura)

If the structure of the Taj Mahal is masculine engineering, its surface is feminine jewelry. The walls are not painted; they are painted with stone. This is Parchin Kari, often known by the Italian term Pietra Dura.

While the technique—inlaying hard stones into marble—existed in Europe, the Mughals adapted it to their own naturalistic sensibilities. In the Shah Jahan era, the geometric stars of earlier times were replaced by flowers: tulips, lilies, irises, and poppies.

The precision is terrifying. A single flower, no larger than a human hand, might be composed of 60 individual pieces of stone.

- Cornelian (orange/red) from Baghdad.

- Lapis Lazuli (blue) from Afghanistan.

- Turquoise from Tibet.

- Malachite (green) from Russia.

- Jasper from Punjab.

- Jade from China.

The artisans sliced these stones into wafer-thin sections, shaped them on bow-lathes, and then chiseled out the marble base with such exactitude that when the stone was inserted, the gap was invisible to the naked eye. No glue was used; the fit was tight enough to hold, though a secret recipe of lime, molasses, and pulses was used as a binding agent.

This floral obsession was not merely decorative. In Islamic mysticism, the garden is a symbol of the soul, and flowers are the manifestation of divine beauty. By covering the tomb of his wife with eternal flowers that would never wilt, Shah Jahan was literally wrapping her in a blanket of Paradise.

Chapter 5: The Lahore Connection – Jahangir’s Tomb

While the Taj Mahal attracts the world's gaze, the Shahjahani legacy in Lahore offers a fascinating counter-narrative. The Tomb of Jahangir, located in Shahdara on the banks of the Ravi River, was commissioned by Shah Jahan (though heavily influenced by Empress Nur Jahan) and completed around 1637, just as the Taj Mahal was rising.

Here, we see a striking difference in style, dictated by the wishes of the deceased. Jahangir, a lover of nature and a man of Sunni piety, had requested that his tomb be open to the sky, like that of his ancestor Babur, so that the rain and dew of God’s mercy could fall upon him.

Consequently, the tomb has no dome. It is a vast, single-story square plinth with tall octagonal minarets at the corners. It is built primarily of red sandstone inlaid with white marble motifs—specifically, ewers (wine jugs) and fruit dishes. This is a touching tribute to Jahangir’s hedonistic lifestyle and his love for the good things in life.

The interior of Jahangir’s tomb, however, is pure Shahjahani opulence. The corridor ceilings are covered in exquisite frescoes, and the floor is a complex mosaic of stone. The cenotaph itself is a masterpiece of white marble, inscribed with the 99 names of Allah in black marble inlay. It is said to be one of the finest examples of calligraphy in the subcontinent.

The absence of a dome makes the minarets the focal point. Clad in zig-zag patterns of variegated marble, they rise like watchtowers. This monument bridges the gap between the robust red sandstone of Akbar and the refined inlay work of Shah Jahan.

Chapter 6: The Forgotten Experiment – Tomb of Asaf Khan

Just west of Jahangir’s tomb lies the shattered husk of what was once a crucial architectural link: the Tomb of Asaf Khan. Asaf Khan was the brother of Nur Jahan and the father of Mumtaz Mahal. He was the Grand Vizier and the man who secured the throne for Shah Jahan.

When he died in 1641, Shah Jahan ordered a tomb befitting a king. Historically, this structure was a "laboratory" for the Taj Mahal. It featured a high, bulbous double dome (the shape of which mirrored the Taj) and an octagonal plan.

Tragically, the tomb was stripped of its white marble facing during the Sikh period in the 19th century to build pavilions in the Golden Temple (Amritsar). Today, it stands as a skeleton of brick. However, what remains is equally precious. The exposed brickwork reveals the structural engineering of the dome. More importantly, the spandrels of the arches still retain fragments of Kashi Kari—glazed tile work.

Unlike the pietra dura of Agra, Lahore’s architecture favored glazed tiles due to the influence of Persia and Central Asia. The tiles on Asaf Khan’s tomb display the cuerda seca technique, where different colored glazes (yellow, orange, green, blue) are separated by a greasy cord during firing to prevent running. This allows for complex, polychromatic floral designs on a single tile. The presence of these tiles proves that Shah Jahan’s aesthetic was not monolithic; it adapted to the local materials and traditions of his empire’s different capitals.

Chapter 7: The "Hasht Bihisht" and the Philosophy of Death

All these mausoleums share a common floor plan known as Hasht Bihisht (Eight Paradises). Originating in Persia, this plan consists of a central chamber (holding the cenotaph) surrounded by eight smaller rooms or bays (four in the corners, four in the cardinal directions).

This is not just a convenient layout; it is a cosmogram. The eight rooms represent the eight levels of Paradise in Islamic cosmology. The central chamber, where the body lies, is the symbolic center of the universe, the point of ascension.

In the Taj Mahal, this plan is executed with perfect symmetry. The eight surrounding rooms are two stories high, creating a complex web of views and light. The light enters through marble screens (jalis), carved so finely that they look like lace. These screens filter the harsh Indian sun, creating a soft, ethereal glow that bathes the cenotaph. The play of light and shadow changes throughout the day, making the marble appear to breathe—blushing pink at dawn, blinding white at noon, and somber blue at twilight.

Chapter 8: The Calligraphic Voice

The walls of Shah Jahan’s tombs speak. The calligraphy, usually executed in the Thuluth script, was designed by master calligraphers like Amanat Khan (who signed his work on the Taj Mahal, a rare privilege).

The inscriptions are not random. They are carefully selected passages from the Quran that speak of the Day of Judgment and the mercy of God.

- The optical correction: The calligraphers knew that the inscriptions high up on the great arches would look smaller to a viewer on the ground due to perspective. To retain aesthetic balance, they progressively increased the size of the letters as they went higher. To the naked eye standing below, the letters look perfectly uniform from top to bottom—a feat of mathematical artistry.

Chapter 9: The Decline – Aurangzeb and the "Poor Man’s Taj"

Shah Jahan’s obsession with architecture eventually contributed to his downfall. The treasury was strained (though not emptied, as some myths claim) by his grand projects. When his son Aurangzeb took the throne after a bloody war of succession, the era of grand mausoleums effectively ended. Aurangzeb was an austere ruler who frowned upon such extravagance, believing that graves should be open to the sky and unmarked, in the orthodox manner.

However, the shadow of the Taj Mahal was long. In Aurangabad, a mausoleum was built for Aurangzeb’s wife, Dilras Banu Begum. Known as the Bibi Ka Maqbara (Tomb of the Lady), it was commissioned by her son Azam Shah but clearly mimics the Taj.

Often called the "Poor Man’s Taj," it reveals the decline of the empire. The scale is smaller. The symmetry is slightly off. Crucially, due to budget constraints, only the main dome and part of the walls are marble; the rest is plaster and stucco designed to look like marble. The delicate pietra dura is replaced by painted floral sprays. It is a beautiful building in its own right, but when compared to the Taj, it serves as a melancholy bookend to the Shahjahani era—a reminder that the golden moment of perfect proportion and unlimited resources had passed.

Chapter 10: Conservation and the Modern Legacy

Today, the mausoleums of Shah Jahan face a new enemy: the modern world. The Taj Mahal’s marble is suffering from "marble cancer," turning yellow due to sulfur dioxide emissions from local industries and oil refineries. The Indian government has established the "Taj Trapezium Zone," a protected area where emissions are strictly controlled.

To combat the yellowing, conservationists use a traditional beauty treatment called Multani Mitti (Fuller’s earth). A lime-rich mud pack is applied to the marble, left to dry, and then washed off with distilled water, absorbing the impurities from the stone's pores.

Furthermore, the drying of the Yamuna River poses a structural threat. The timber wells of the foundation need moisture to prevent rot. As the water table drops, the wood risks becoming brittle, potentially destabilizing the massive weight of the dome. It is a race against time to preserve these structures that were built to last forever.

Epilogue: A Symphony in Stone

The mausoleums of Shah Jahan are more than just graves. They are the crystallization of an empire’s highest cultural aspirations. They represent a moment in history where the wealth of India, the theology of Islam, and the artistic traditions of Persia fused to create something unique.

From the silent, dome-less peace of Jahangir’s resting place to the soaring, ethereal perfection of the Taj Mahal, these structures tell the story of a dynasty that sought to bring the order of the stars down to the chaos of the earth. Shah Jahan may have died a prisoner in the Agra Fort, gazing at the Taj Mahal from a distance, but in the end, he achieved his goal. He built a legacy that death could not erase.

Reference:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taj_Mahal

- https://travelsetu.com/guide/shah-jahan-s-mosque-tourism/shah-jahan-s-mosque-tourism-history

- https://studydriver.com/taj-mahal-tomb-as-a-symbol-of-india/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHQao6XKarU

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ustad_Ahmad_Lahori

- https://www.newageislam.com/islamic-personalities/adnan-faizi-new-age-islam/ustad-ahmad-lahori-architectural-visionary-mughal-india/d/135537

- https://tourism.punjab.gov.pk/jahangir-tomb

- https://www.archdaily.com/100528/ad-classics-taj-mahal-shah-jahan

- https://worldofstones.in/blogs/news/pietra-dura

- https://mapacademy.io/asif-khans-tomb-the-experiment-that-shaped-the-taj-mahal/

- https://architecturalanatomyblog.wordpress.com/2017/06/28/tomb-of-jahangir-lahore/

- https://heritageofpakistan.org/punjab/tomb-of-emperor-jahangir/

- https://walledcitylahore.gop.pk/jahangir-tomb/

- https://www.theislamicheritage.com/detail/Ajmer-Sharif-Dargah-Ajmer

- https://grave-stories.com/the-taj-mahal-the-most-beautiful-mausoleum-in-the-world/

- https://www.mausoleums.com/taj-mahal-mausoleum/

- https://pakheritage.org/tomb-of-asif-khan/

- https://www.rezovate.com/blogs-for-industries/the-art-of-construction-taj-mahal