The Caribbean Sea, usually a turquoise playground for tourists, hides a darker, colder secret some 600 meters beneath its surface. For over three centuries, it has held the broken spine of the San José, a Spanish galleon that took 600 souls and an empire’s fortune to the bottom in 1708. Often called the "Holy Grail of Shipwrecks," its cargo of emeralds, gold, and silver has haunted treasure hunters for generations. But the true revolution isn't the bullion; it is the machine hand that recently reached out to touch it.

As of late 2025, the world watched in awe as the Colombian government confirmed the successful recovery of the first artifacts from this abyssal grave. This feat was not accomplished by divers in wetsuits, but by avatars of steel and silicon—advanced deep-sea robots that have turned the San José into the world's deepest, most high-tech archaeological dig.

This is the story of how robotics is rewriting history, transforming a legendary tragedy into a triumph of maritime archaeology.

The Ghost of 1708

To understand the magnitude of the extraction, one must first understand the loss. On June 8, 1708, the San José was the flagship of the Spanish treasure fleet, sailing from Portobelo, Panama, to Cartagena. Its hold was groaning under the weight of taxation from the Spanish colonies: chests of Peruvian emeralds, millions of gold and silver coins struck in the Andes, and personal fortunes of viceroys.

It never reached port. Near the Barú Peninsula, the fleet was ambushed by a British squadron led by Commodore Charles Wager. The British intended to capture the ship and its prizes, but in the heat of the cannonade, the San José’s powder magazine detonated. The explosion was apocalyptic. The massive vessel shattered and vanished almost instantly, taking its captain, the general of the fleet, and nearly the entire crew to the seafloor.

For 307 years, the wreck remained a ghost story, its location a mixture of myth and conjecture, until the silence was broken in 2015.

The Discovery: A Triumph of Autonomous Technology

The 2015 discovery of the San José was not a stroke of luck; it was a masterpiece of engineering led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and the Colombian Navy. The hero of this chapter was the REMUS 6000, an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV).

Unlike traditional ship-tethered sonars, the REMUS 6000 is a torpedo-shaped robot capable of "mowing the lawn"—scanning vast swathes of the ocean floor autonomously with side-scan sonar. It identified the wreck not by the glint of gold, but by the geometric unnaturalness of bronze cannons scattered on the seabed. Specifically, the dolphin engravings on the cannons, captured in high-resolution photos by the AUV’s cameras just meters above the bottom, provided the positive identification needed to confirm the ship's identity.

The "Robotic Archaeologist": Engineering the Extraction

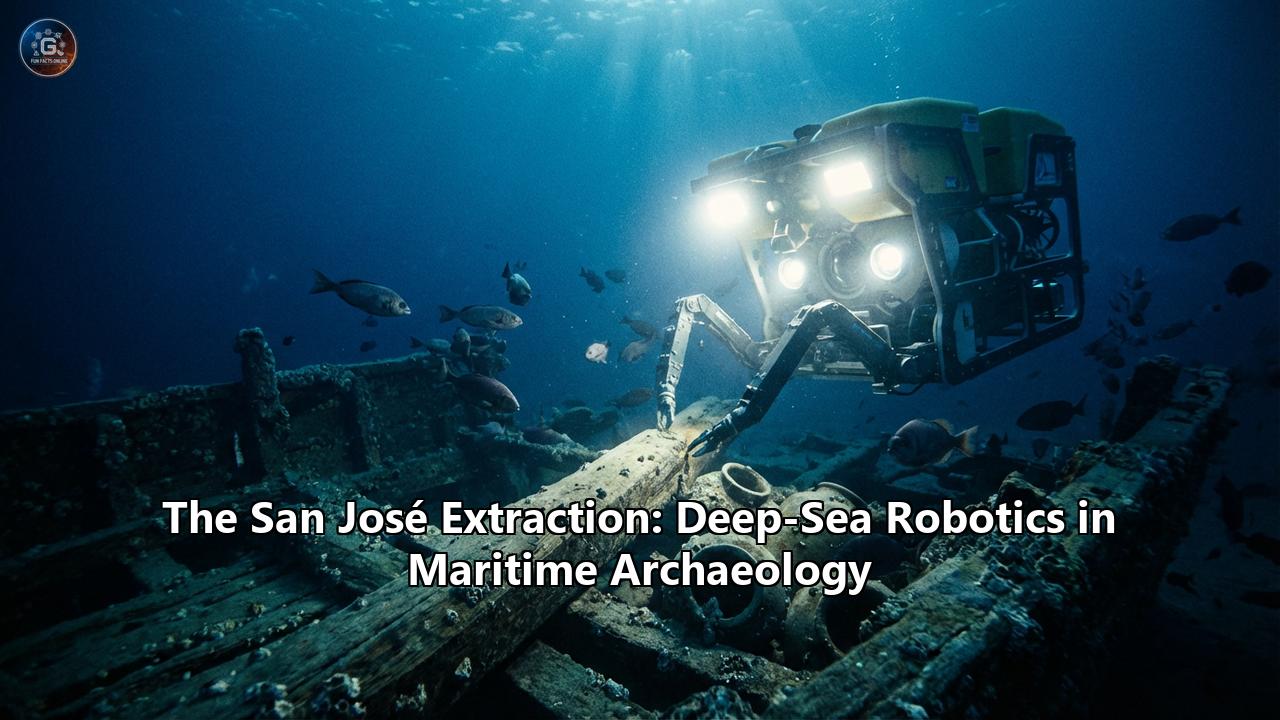

The transition from finding the ship to touching it represents a quantum leap in maritime capability. At 600 to 900 meters deep, the environment is hostile. The pressure is crushing (roughly 60 to 90 atmospheres), the darkness is absolute, and the currents can be unpredictable. No human diver can work here. The archaeologist must become a pilot, operating through the eyes and hands of a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV).

The Machine Interface

The recovery operation, code-named "Towards the Heart of the San José Galleon," utilized a specialized heavy-work class ROV. These machines are the size of a minivan, tethered to a mothership on the surface by an umbilical cord that transmits power and massive amounts of data.

The ROV is equipped with a suite of sensory equipment that makes it "hyper-aware" of its surroundings:

- 4K and 8K Cameras: Providing clarity superior to the human eye, allowing archaeologists on the surface to inspect the hallmark of a coin or the glaze of a teacup in real-time.

- Laser Scalers: Projecting parallel laser beams onto objects to measure their size precisely without physical contact.

- Sub-bottom Profilers: Acoustic tools that can "see" through the sediment, revealing artifacts buried meters deep in the mud without digging.

The Soft Touch of Hard Metal

The most critical challenge in the 2024-2025 extraction phase was the physical interaction with the artifacts. A standard hydraulic claw, designed for oil rig valves, would crush a Ming dynasty porcelain cup into dust.

To solve this, the mission employed soft robotics and force-feedback (haptic) technology.

- Soft Grippers: Unlike rigid claws, these end-effectors mimic the human hand, often using silicone fingers inflated with fluid to gently wrap around an object. They conform to the shape of a fragile artifact—like a 300-year-old ceramic jug—distributing pressure evenly to prevent cracking.

- Suction Limpets: For objects partially buried, low-flow suction devices (dredges) act like gentle vacuum cleaners, removing centuries of silt without the abrasive violence of a standard commercial dredge.

- Variable Buoyancy Lift Systems: Once an object is gripped, it isn't just yanked up. It is placed in a basket with its own buoyancy control, or "elevator," which gently ascends to the surface at a controlled rate to manage the change in pressure.

In November 2025, this technology proved its worth. The world saw the first fruits of this labor: a bronze cannon, a pristine porcelain cup, and silver coinage. They were not encrusted lumps, but recognizable treasures, handled with the delicacy of a surgeon by a robot pilot sitting in an air-conditioned control room kilometers above.

The Science of Survival: Conservation

Bringing an artifact up from the deep is a traumatic event for the object. For three centuries, materials like wood and iron have reached an equilibrium with the saltwater. The iron is saturated with chlorides (salts), and the wood’s cellular structure is often held up only by the water inside it.

If a wooden timber from the San José were simply brought to the surface and allowed to dry, the water would evaporate, and the cells would collapse, turning the wood into dust. If an iron cannon were exposed to oxygen without treatment, it would rapidly corrode and disintegrate.

The Colombian Navy, in partnership with archeological institutes, has established a world-class conservation facility in Cartagena specifically for this project. The protocols are rigorous:

- Desalination: Artifacts are immediately placed in tanks of chemical solutions to gradually leach out the salts. This process can take years for large cannons.

- Electrolysis: To save the metal, artifacts are hooked up to an electrical current in a bath of electrolytes. This reverses the oxidation process, converting the rusty crust back into stable metal or allowing it to be safely removed.

- PEG Impregnation: For organic materials, the water is slowly replaced with Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), a wax-like substance that bulks up the cell walls, ensuring the wood keeps its shape even when dry.

The War for Ownership: A Legal Maelstrom

While the robots work silently in the deep, the surface is noisy with legal and diplomatic thunder. The San José is not just a shipwreck; it is a geopolitical flashpoint.

1. Colombia’s Stance:For Colombia, the wreck is part of its submerged cultural heritage. The government, particularly under the administration leading the 2025 recovery, has pivoted the narrative from "treasure" to "heritage." They argue that the ship lies in their territorial waters and that they have the sovereign right to manage it. They have declared the site a "Protected Archaeological Area."

2. Spain’s Claim:Spain argues that the San José was a "State Vessel"—a warship of the Spanish Armada. Under international maritime law (and the UNESCO convention, which Colombia has not signed), warships remain the property of their flag state regardless of where or when they sink. Spain views the site as a war grave for its 600 sailors and has historically opposed commercial salvage.

3. Sea Search Armada (SSA):This group of American investors claims to have located the wreck initially in the early 1980s (a claim Colombia disputes, stating the coordinates were wrong). They have engaged in a decades-long legal battle, demanding 50% of the "treasure's" commercial value, estimated at up to $20 billion.

4. The Bolivian Indigenous Claim:Perhaps the most morally compelling claim comes from the Qhara Qhara nation of Bolivia. They argue that the gold and silver in the galleon’s hold were mined from the bowels of the Andes (Potosí) by their enslaved ancestors. To them, the "treasure" is blood money that should be returned to the people from whom it was stolen.

Beyond Gold: The True Value

As the robotic arms of the San José expedition continue their work, a shift in perspective is occurring. The initial headlines screamed about billions of dollars in gold. But the artifacts recovered in late 2025 tell a more human story.

The porcelain teacups speak of the global trade networks connecting China, the Americas, and Europe. The personal armaments reveal the fear of the crew in pirate-infested waters. The coins are not just currency; they are historical documents stamped with the date and place of their creation, offering a snapshot of the colonial economy.

The extraction of the San José is a testing ground for the future of archaeology. It proves that we can access the deepest museums on Earth without destroying them. We are no longer smashing and grabbing; we are visiting and learning.

The "Holy Grail" has been found, but the real treasure isn't what we can melt down and sell. It’s the technology that allows us to reach back through the crushing depths of time and ocean to hold history in our hands, intact and unspoken, for the first time in 300 years.

Reference:

- https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/new-details-on-discovery-of-the-san-jose-shipwreck/

- https://colombiaone.com/2024/05/24/san-jose-galleon-ship-protected-area-colombia/

- https://apnews.com/general-news-1dfdface8b074eb28e8fe9cce48b7561

- https://english.elpais.com/culture/2023-11-25/colombia-aims-to-salvage-the-sunken-treasure-of-the-san-jose-but-experts-remain-skeptical.html

- https://www.chosun.com/english/world-en/2025/11/21/OMF7CFQE6JFR5OPCQ2ZOAWLDRY/

- https://nzdrc.co.nz/the-treasure-of-the-san-jose/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_galleon_San_Jos%C3%A9

- https://shiprex.net/2013/09/10/preserving-artifacts-from-shipwrecks/

- https://www.jpost.com/archaeology/archaeology-around-the-world/article-833492

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j2fMPYiT0SI

- https://www.scribd.com/document/244071291/Assignment-2

- https://thecitypaperbogota.com/culture/colombia-to-recover-artifacts-from-san-jose-galleon-in-2024/