In the annals of archaeological discovery, we are accustomed to tales of grueling expeditions. We imagine pith-helmeted explorers hacking through mosquito-choked rainforests with machetes, battling dysentery and dehydration for months before stumbling upon a moss-covered ruin. We think of Hiram Bingham at Machu Picchu or Howard Carter peering into the gloom of Tutankhamun’s tomb. We rarely think of a graduate student sitting in an air-conditioned office, scrolling through the sixteenth page of Google search results.

Yet, in 2024, that is exactly how one of the most significant Maya discoveries of the last century was made. Luke Auld-Thomas, a PhD candidate at Tulane University, was not looking for a lost city. He was looking for data. Specifically, he was hunting for lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) surveys—laser mapping data that could peer through the dense canopy of the Mexican jungle.

Most archaeological lidar surveys are purpose-built and exorbitantly expensive, funded by major grants and universities. But Auld-Thomas had a hunch. He suspected that other industries—forestry, environmental monitoring, carbon capture analysis—might have already mapped parts of the Yucatan Peninsula for their own reasons. So, he went digging in the deep web.

On roughly page 16 of his search results—a digital graveyard where few users ever venture—he found it. It was a file buried in a 2013 environmental monitoring report commissioned by the Nature Conservancy. The objective of the original survey had been to measure the biomass of the forest to monitor carbon levels. The surveyors were looking at the trees; they didn't care about the bumps on the ground beneath them.

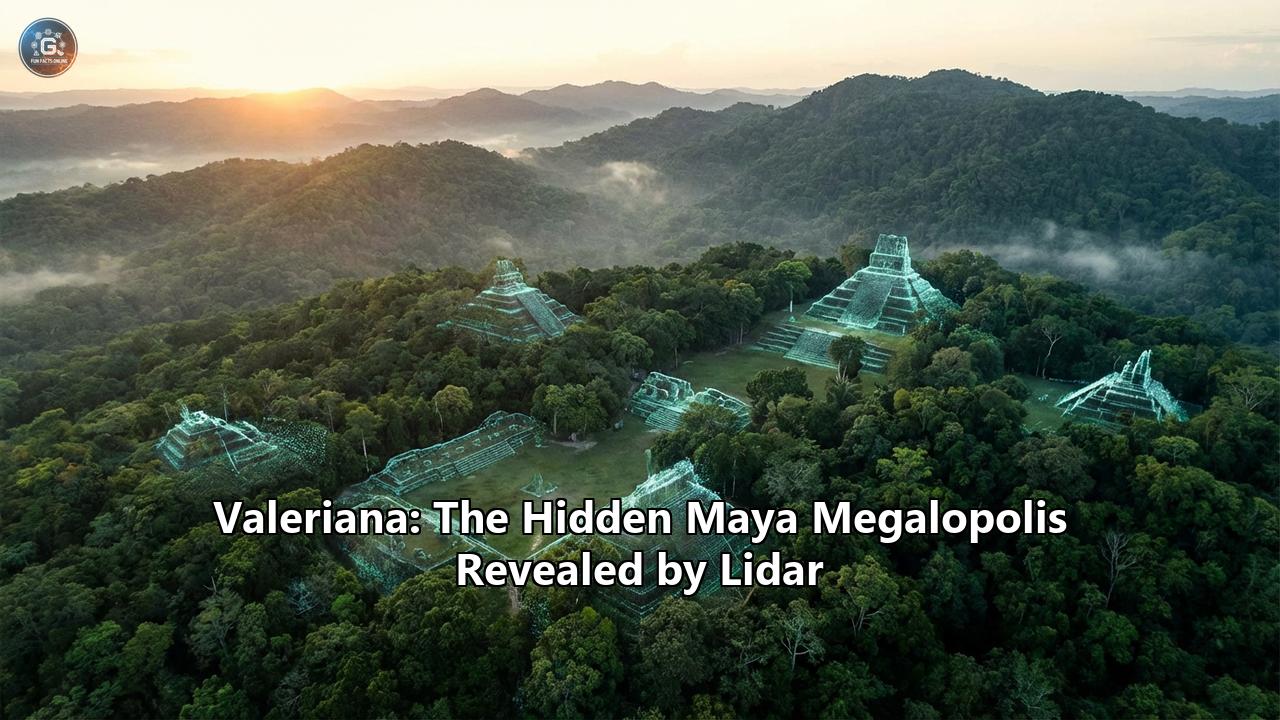

But when Auld-Thomas processed the data using archaeological algorithms, stripping away the digital vegetation, the screen didn't show a flat forest floor. It showed a city.

It wasn't just a small outpost or a rural hamlet. It was a megalopolis. A sprawling urban landscape of 16.6 square kilometers, packed with over 6,700 structures. There were temple pyramids rising nearly as high as those at the famous site of Chichén Itzá. There were enclosed plazas, broad causeways, reservoirs, and a ritual ballcourt. It was a city that had once been home to perhaps 50,000 people—a population larger than the modern region today.

They named it Valeriana, after a nearby freshwater lagoon. And perhaps the most shocking detail of all? It was hiding in plain sight. The ruins lie just a 15-minute walk from a major paved highway near Xpujil, Mexico. Farmers have been cultivating crops among its ancient foundations for decades, unaware that beneath their feet lay the capital of a lost political dynasty.

This is the story of Valeriana: the city that changes everything we thought we knew about the Classic Maya civilization.

Part I: The Magic of "Digital Deforestation"

To understand the magnitude of the Valeriana discovery, one must first understand the technological revolution that made it possible. For over a century, Maya archaeology was a game of pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey. The Maya Lowlands—spanning southern Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize—are covered in some of the densest tropical forests on Earth.

A ruin standing fifty feet away can be completely invisible behind a wall of vines and mahogany trees. Early archaeologists could spend entire careers mapping a single city, cutting survey lines by hand. They naturally assumed that the areas between these known cities were empty—vast, uninhabited buffers of wilderness where jaguars roamed and few humans lived.

Lidar changed the paradigm overnight.

Lidar works by mounting a laser scanner on an aircraft (or sometimes a drone) and flying it over the target area. The scanner fires hundreds of thousands of laser pulses per second at the ground. Most of these pulses hit the tops of trees and bounce back. But a small fraction—sometimes less than 1%—slip through gaps in the leaves and hit the earth below.

By measuring the time it takes for those specific pulses to return, a computer can calculate the distance to the ground with incredible precision. Software then filters out the "noise" of the trees, effectively deleting the forest from the image.

Archaeologists call this "digital deforestation." The result is a naked 3D model of the terrain, revealing every man-made modification: house platforms, irrigation canals, defensive walls, and causeways.

When Auld-Thomas applied this process to the 2013 environmental data, the results were staggering. The survey covered about 50 square miles (130 square kilometers) of the state of Campeche. This region was historically considered a "blank spot" on the archaeological map—a hinterland between the known Chenes region to the north and the Rio Bec region to the south.

The scan revealed that this "empty" space was not empty at all. It was crowded.

The density of structures in Valeriana—55.3 buildings per square kilometer—is second only to Calakmul, the mightiest of all Maya superpowers in the region. This statistic is the smoking gun that shatters the "vacant wilderness" theory. If a city the size of a modern capital can hide in a "blank spot" on the map, it implies that the Maya Lowlands were not a scattering of isolated city-states separated by jungle. They were a continuous, semi-urban landscape, more akin to the sprawling density of modern suburban New Jersey or the Netherlands than the isolated clusters previously imagined.

Part II: Walking the Streets of Valeriana

Though no archaeologist has yet conducted a full-scale excavation of Valeriana, the high-resolution lidar data allows us to take a virtual tour of the city as it stood at its peak, roughly 800 AD.

The Lay of the LandValeriana is not a monolithic block. It is a "poly-nucleated" city, meaning it has multiple centers. The urban sprawl connects two primary monumental precincts located about two kilometers apart. Between them lies a dense continuous settlement of houses, terraces, and smaller district centers. This layout reflects a complex social organization, suggesting that Valeriana grew over centuries, perhaps absorbing smaller neighboring towns into its orbit.

The Monumental CoreThe main precinct is a display of raw imperial power. It features all the hallmarks of a Classic Maya political capital.

- The Pyramids: The city is dominated by large temple pyramids. While exact heights await ground verification, comparisons with the nearby Chactún-Tamchen architectural style suggest these structures could rise upwards of 20 to 25 meters (65 to 80 feet). These were the stages for public theater—sacrifices, coronations, and astronomical alignments.

- The E-Group: Perhaps the most scientifically significant feature identified is an "E-Group" assemblage. This specific architectural arrangement consists of a western pyramid facing a raised platform with three smaller structures to the east. To an observer standing on the western pyramid, the eastern structures mark the sunrise on the solstices and equinoxes.

Significance: E-Groups are very old. Their presence at Valeriana indicates that the city was not just a late boomtown; it likely has roots stretching back to the Preclassic period (before 150 AD). This city had been an anchor of the landscape for nearly a millennium before its collapse.

- The Ballcourt: Like all major Maya cities, Valeriana has a masonry ballcourt. The Maya ballgame was not merely sport; it was a ritual re-enactment of the creation myth, a battle between the Heroes Twins and the Lords of the Underworld. Its presence confirms Valeriana's status as a seat of religious authority.

One of the most impressive features visible on the scan is a dammed reservoir formed by blocking a seasonal arroyo (creek). The Maya of the Classic period were master hydrologists. In a region with a distinct dry season and no major rivers, catching and storing rain was a matter of life and death. The reservoir at Valeriana would have been a massive public works project, capable of sustaining thousands of people through the parched months. It symbolizes the social contract between the rulers and the ruled: the King’s power was justified by his ability to provide water.

The ArchitectureArchitecturally, Valeriana appears to share traits with the Chactún-Tamchen style found to the southeast. This style is characterized by massive volumes of stone, large enclosed plazas, and stelae (stone monuments) that often bear hieroglyphic texts. It is distinct from, though related to, the famous Rio Bec style found at nearby Xpujil. Rio Bec architecture is famous for its "false towers"—non-functional staircases that create an optical illusion of steepness. Whether Valeriana employs these specific optical tricks or the more functional monumentalism of Chactún is a question that will only be answered when boots hit the ground.

Part III: The People of the Megalopolis

Who lived in Valeriana?

If you were a resident of this city in 750 AD, your life was defined by density. You were not living in a lonely hut in the woods. You were likely living in a house compound—three or four stone buildings facing a central patio—surrounded by neighbors on all sides.

The lidar shows a landscape that is "completely full." Every inch of available land between the houses was terraced for agriculture. The Maya were experts at intensive farming. They built terrace walls to stop soil erosion, created "raised fields" in wetlands, and managed kitchen gardens rich in avocado, chili, squash, and maize.

The population estimate of 30,000 to 50,000 is staggering. To put that in perspective, that is roughly the population of a modern city like Atlantic City, New Jersey, or frantic, bustling medieval London.

But Valeriana was not just a city of farmers. The sheer scale of the monumental architecture implies a heavy top-tier of society:

- The Divine Lords (K’uhul Ajaw): A royal dynasty would have ruled here. They would be the ones commissioning the pyramids and stelae.

- The Court: A strata of scribes, astronomers, priests, and minor nobles who managed the bureaucracy of the state.

- Artisans: Stonemasons to build the temples, jade carvers, potters, and weavers.

- Engineers: Experts to maintain the reservoir and the causeway systems (sacbeob) that connected Valeriana to the wider world.

The discovery of Valeriana paints a picture of a cosmopolitan society. The variation in building density—from the crowded urban core to the "suburban" agricultural belts—suggests a complex social hierarchy where inequality was built into the landscape itself.

Part IV: The "Full Landscape" and the Great Collapse

The discovery of Valeriana contributes a crucial piece to the puzzle of the Maya Collapse.

For decades, scholars have debated why this magnificent civilization imploded between 800 and 1000 AD. Theories have ranged from drought and warfare to overpopulation and environmental degradation. Valeriana supports the "systemic stress" theory.

Luke Auld-Thomas noted in his analysis that the landscape at Valeriana was "brittle."

"It’s suggesting that the landscape was just completely full of people at the onset of drought conditions and it didn’t have a lot of flexibility left," he told reporters.

Imagine a bucket filled to the absolute brim with water. The surface tension is holding it together, but it is precarious. The Maya had engineered their environment to the limit. They had cut down the forest to plant corn; they had paved over the watershed for plazas; they had maximized every square meter of soil to feed a booming population.

When the climate turned—when the severe multi-decadal droughts of the 9th century hit—there was no buffer. There was no "empty forest" to retreat to because, as Valeriana shows, the forest was already full of other people.

The interconnectedness that made Valeriana strong—its trade routes, its dense population, its shared water management—became its weakness. When the crops failed in one sector, the ripple effect would have been immediate and catastrophic. The reservoir dried up. The King could no longer guarantee the water. The social contract broke.

The lidar data shows that Valeriana, like Calakmul and Tikal, was eventually abandoned. The jungle reclaimed the plazas. The wooden roofs of the palaces rotted away, and the stone vaults collapsed. For a thousand years, the mahogany trees grew thick over the E-Group temple, hiding it from the Spanish Conquistadors, the loggers of the 20th century, and the tourists driving on the highway just a mile away.

Part V: The Irony of Discovery

There is a profound irony in the story of Valeriana.

Usually, we assume that scientific discoveries come from looking closer—building more powerful microscopes or traveling to more remote frontiers. Valeriana was found by looking backwards at data we already had.

The dataset had been sitting on servers for a decade. It was collected for a noble but entirely different purpose: measuring carbon stocks to fight climate change. The scientists who commissioned the flight were forestry experts. When they looked at the point-cloud data, they saw trees. They filtered out the ground because, to them, the ground was "noise."

Archaeologists do the opposite. They filter out the trees to see the ground.

This highlights a new era of "Data Archaeology." We are generating so much digital information about our planet—via satellites, street-view cars, weather drones, and environmental surveys—that we cannot process it all in real-time. Discoveries are no longer just about going to the field; they are about mining the archives.

How many other "Valerianas" are sitting on a hard drive in a government office in Brazil, Cambodia, or the Congo?

The location of Valeriana adds another layer of irony. It is not in an inaccessible biosphere reserve. It is near Xpujil, a town with hotels and restaurants. It is near Becán and Chicanná, famous tourist sites. Thousands of tourists have likely driven past Valeriana on their way to Calakmul, gazing out the bus window at a "hill" that was actually a buried pyramid.

Local farmers knew there were "mounds" in the forest. They have been plowing around them for generations. But the scientific community—and the world at large—had no idea that these mounds connected to form a coherent, massive urban entity until a student checked page 16.

Part VI: The Future of Maya Archaeology

The discovery of Valeriana forces a reckoning in the field of archaeology.

The Impossible Math of ExcavationWe now know that the Maya world is vastly more populated than we thought. If you extrapolate the density of Valeriana across the unmapped portions of Campeche and Guatemala, the number of "lost cities" could be in the hundreds.

We cannot excavate them all.

Archaeology is slow, destructive, and expensive. Digging a single plaza takes years and millions of dollars. Conserving the ruins once they are exposed costs even more. If we uncovered Valeriana tomorrow, the jungle would try to eat it again the day after.

This leads to a new ethical and logistical reality. Lidar allows us to "discover" sites without touching them. We can map the politics, the economics, and the demographics of the ancient Maya without ever lifting a trowel.

The "Do No Harm" ApproachFor now, there are no immediate plans to excavate Valeriana. This is partly due to funding, but also due to preservation. As long as the city remains under the soil and the trees, it is safe. It is safe from looters (who prefer easier targets), safe from acid rain, and safe from the wear and tear of tourism.

However, the knowledge of its existence puts it at risk. Now that the coordinates are known (roughly), the site becomes vulnerable to looters looking for jade or polychrome pottery. The Mexican government (INAH) and the local communities will face the challenge of protecting a city that is too large to fence off.

A New Map of the PastValeriana joins a growing list of Lidar superstars—Ocomtún (discovered in 2023 by Ivan Sprajc), Aguada Fénix (the massive ceremonial platform in Tabasco), and the sprawling suburbs of Tikal.

Together, these sites are rewriting the history books. We are moving away from the idea of the Maya as a mysterious people living in harmony with a virgin rainforest. We are moving toward a view of the Maya as the "Greeks of the New World"—a civilization of high-density city-states that engineered their landscape on a massive scale, quarreled, traded, and eventually outgrew their environment.

ConclusionLuke Auld-Thomas hasn’t visited Valeriana yet. He has walked its streets only in the digital realm, flying through the point-cloud on his computer screen.

"I’ve got to go to Valeriana at some point," he said in an interview. "It’s so close to the road, how could you not?"*

When he finally does step out of the car near Xpujil and walks into that patch of forest, he won't be hacking through the "primeval" jungle. He will be walking into a graveyard of ambition. He will be walking over the terraces where families once argued over property lines. He will be standing in the shadow of pyramids where kings once commanded the rain.

Valeriana is a reminder that the world is not fully explored. It is also a warning. It shows us a civilization that was crowded, complex, and sophisticated—and which pushed its world a little too far. In the age of climate change and urbanization, the ghost city on page 16 has never been more relevant.

Reference:

- https://news.artnet.com/art-world/lidar-reveals-lost-mayan-city-valeriana-2561336

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Hh70tv8cfo

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valeriana_(archaeological_site))

- https://bigthink.com/strange-maps/lidar-finds-valeriana/

- https://www.ladbible.com/news/uk-news/student-discovery-maya-city-mexico-valeriana-505926-20241029

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chact%C3%BAn

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/found-dataset-reveals-lost-maya-city-hiding-in-plain-sight-beneath-a-mexican-forest-180985354/

- https://english.elpais.com/culture/2024-10-30/valeriana-the-ancient-mayan-city-found-thanks-to-laser-imaging.html

- https://mayaruins.com/rio-bec.html

- https://www.jpost.com/archaeology/archaeology-around-the-world/article-826833

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R%C3%ADo_Bec

- https://www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-maya-ruins-city-chactun-mexico-discovered-yucatan-20130621-story.html

- https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/190924/1/download4.pdf

- https://www.caracol.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ACDC2017-e-groups.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Chactun-and-the-surrounding-area-to-the-southwest-A-Tamchen-B-Lagunita-C_fig4_358034304

- https://yucatantoday.com/en/blog/maya-architectural-styles

- https://ancientmayalife.blogspot.com/2012/08/rio-bec-architecture.html