The earth beneath Mosul is not merely soil; it is a ledger of empires, written in layers of ash, mudbrick, and blood. For three thousand years, the city has stood as a witness to the rise and fall of civilizations, from the iron-fisted rule of the Neo-Assyrian kings to the medieval grandeur of the Zengids, and finally, to the catastrophic occupation by the Islamic State (ISIS) in the 21st century. But in late 2023, from the gloom of a looted tunnel dug by terrorists, a ghost emerged—a spirit of protection that had waited in the dark for nearly three millennia.

They call it the "Mosul Colossus."

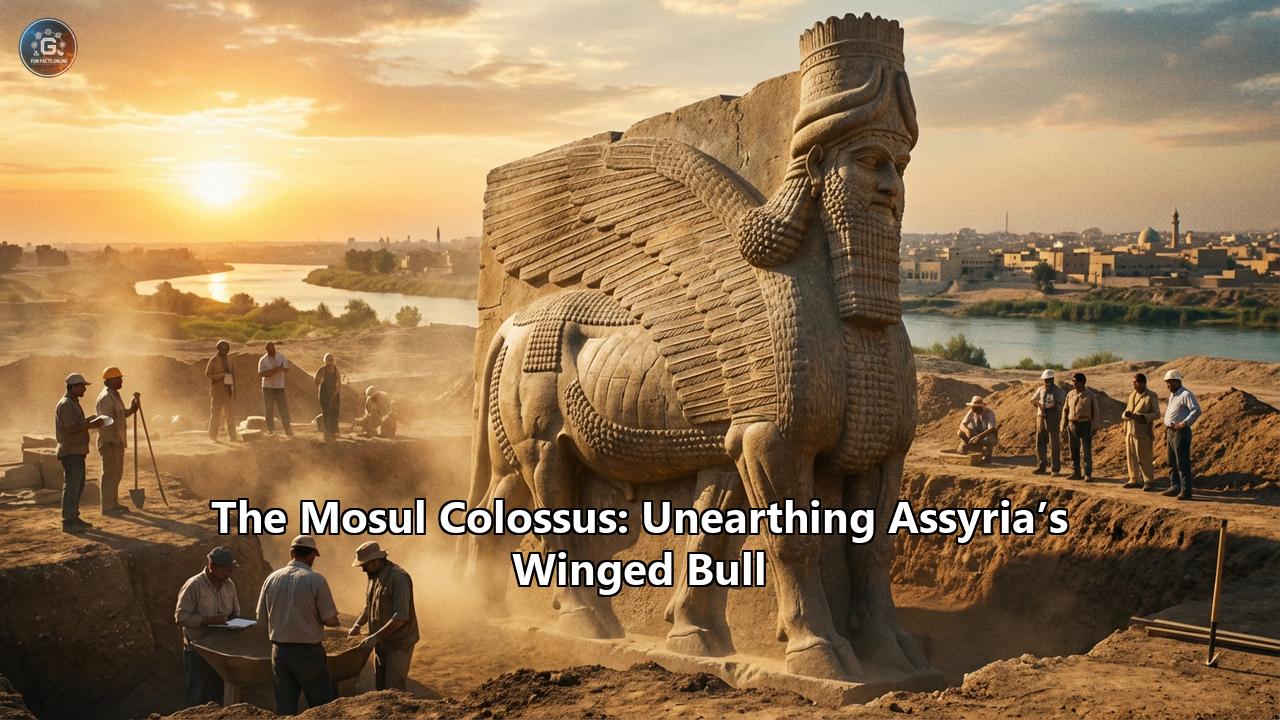

It is a Lamassu—a celestial hybrid with the head of a human, the body of a bull, and the wings of an eagle. Standing nearly 18 tons in weight and carved from a single block of translucent gypsum alabaster, it is one of the largest and most pristine examples of Assyrian monumental art ever recovered. Its rediscovery is not just an archaeological triumph; it is a story of survival. This creature has survived the fall of Sargon II, the neglect of centuries, the greed of 19th-century colonial excavators, and the jackhammers of modern zealots.

This is the definitive story of the Mosul Colossus—a journey that takes us from the scented throne rooms of ancient Dur-Sharrukin to the sinking rafts of the Tigris River, and finally to the high-tech resurrection of a city reclaiming its soul.

Part I: The Guardians of the Gate

To understand the Colossus, one must first understand the world that necessitated its creation. The Neo-Assyrian Empire (c. 911–609 BCE) was the first true superpower of the ancient world. Its kings—figures like Ashurnasirpal II, Sennacherib, and Sargon II—ruled a territory that stretched from the Zagros Mountains of Iran to the Nile Delta of Egypt. Their power was absolute, maintained by a military machine of terrifying efficiency. But their dominance was not just physical; it was psychological.

The Assyrian capital cities—Nimrud (Kalhu), Nineveh, and Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad)—were designed as machines of intimidation. When a foreign diplomat or a tributary prince approached the royal palace, they were meant to feel small. The architecture was a weapon. The walls soared dozens of meters into the air, painted in blinding stripes of cobalt blue, red ochre, and white. And at every vulnerable point—every gate, every doorway, every threshold—stood the Lamassu.

The Anatomy of a God

The Lamassu (and its female counterpart, the Apsasu) was an apotropaic deity—a figure intended to ward off evil. In the Assyrian worldview, the universe was teeming with chaotic forces: demons, spirits of disease, and the gallu of the underworld. The king, as the earthly representative of the god Ashur, sat at the center of a cosmic order that required constant defense.

The composition of the Colossus is a masterclass in theological symbolism. The human head, crowned with a tiara of three sets of bull horns, represents intelligence and divinity. The bearded face is that of the king himself, freezing his wisdom in stone. The body of the bull (or sometimes a lion) represents physical strength and virility, the raw power of the natural world harnessed by the state. The wings of the eagle, sweeping backward in intricate feather patterns, represent swiftness and a connection to the heavens.

But the true genius of the Lamassu lies in its perspective. These statues were not meant to be viewed as static objects in a museum. They were architectural machines. If you look closely at the legs of the Mosul Colossus, you will see a strange anomaly: it has five legs.

This was a deliberate optical trick by the Assyrian sculptors. When a visitor approached the gate head-on, they saw the two front legs planted firmly side-by-side. The creature appeared to be standing still, a sentinel blocking the path, demanding submission. However, as the visitor passed through the gate and looked up at the creature from the side, the fifth leg became visible, while one of the front legs disappeared behind the other. Suddenly, the creature appeared to be striding forward. The static guardian became a moving escort, walking alongside the visitor as they entered the presence of the king. It was an animation in stone, a 700 BCE predecessor to the motion picture.

The Sensory Palace

We often imagine these ancient ruins as they appear today: beige, dusty, and silent. This is a mistake. The palace of Sargon II at Dur-Sharrukin, where the Mosul Colossus was born, was a riot of sensory overload.

Recent chemical analyses of pigment traces on similar statues have revealed that the Lamassu were not left as bare stone. They were painted. The beards were likely black or dark blue, using expensive bitumen or Egyptian Blue pigment. The whites of the eyes were enameled, the pupils painted jet black to create a piercing stare. The wings may have been tipped with red and blue, echoing the colorful glazed bricks of the palace walls.

Imagine the experience of an ancient visitor. You walk up a ramp to the citadel, the smell of cedarwood from the massive palace doors (imported from Lebanon) filling the air. You hear the rhythmic chanting of priests, the clinking of bronze sistrums, and the lowing of sacrificial animals. As you reach the gate, you pass between two 40-ton Lamassu, their colors vibrant in the Mesopotamian sun. You are not just entering a building; you are entering the belly of a beast, a space where the boundary between the human and the divine is thin.

Between the legs of the Colossus, inscribed in dense cuneiform, is the "Standard Inscription." It is a text found on nearly every major Assyrian monument, serving as both a résumé and a curse. It lists the king's titles—King of the World, King of Assyria—and his conquests. But it ends with a warning to any future ruler who might deface the statue:

"May Ashur, the father of the gods, and Ishtar, the lady of battle, look upon him with anger, overthrow his kingdom, and blot out his name and his seed from the land."

For 2,700 years, that curse seemed to hold.

Part II: The Great Game of Archaeology

The modern story of the Assyrian bulls begins not in Iraq, but in the gas-lit libraries of Europe. By the 19th century, Nineveh and Babylon were considered by many to be myths, cities that existed only in the pages of the Bible. The Ottoman Empire controlled Mesopotamia, and the mounds of earth dotting the Tigris were largely ignored by the local Pashas, who saw them only as sources of old bricks.

Enter the French and the British.

In 1842, the French government appointed Paul-Émile Botta as consul to Mosul. Botta was a naturalist and a diplomat, but his true passion was the hunt for Nineveh. He began digging at the mound of Kuyunjik, directly across the river from Mosul, but found little but pottery shards.

Desperate and running out of funds, Botta heard a rumor from a local dyer about a village called Khorsabad, a few hours north. The villagers there complained that they couldn't dig foundations for their houses without hitting massive stones carved with "pictures of devils."

Botta moved his operation to Khorsabad. almost immediately, his shovel hit stone. He had not found Nineveh (though he thought he had); he had found Dur-Sharrukin, the "Fortress of Sargon," a capital city built by Sargon II in 706 BCE and abandoned shortly after his death.

Botta unearthing the first Lamassu was a moment of shock. Here were monsters that matched no classical Greek or Roman style. They were alien, terrifying, and undeniably powerful. He wrote to Paris: "I believe I have discovered Nineveh."

The Rivalry: Botta vs. Layard

Across the political divide was Austen Henry Layard, a young British adventurer who would become Botta’s friendly but fierce rival. While Botta dug at Khorsabad, Layard focused on Nimrud (Biblical Calah) and later the true Nineveh at Kuyunjik.

The extraction of these Colossi became a proxy war between the Louvre and the British Museum. It was a "gold rush" for granite and gypsum. The logistics were a nightmare. These statues weighed between 10 and 40 tons. The Assyrians had moved them using thousands of prisoners of war, sledges, and rollers. Botta and Layard had to make do with local villagers, primitive carts, and the fickle Tigris River.

Layard’s accounts of moving the winged bulls from Nimrud are legendary. He describes building a massive cart, which required teams of buffalo and hundreds of men to pull. As the first bull was lowered onto the cart, the ropes strained and snapped. The bull fell, but miraculously landed safely on the soft earth. The villagers, seeing the "beast" move, were terrified, believing the spirit of the Jinni had been awakened.

Botta, lacking the resources of Layard, made a decision that makes modern archaeologists weep: he sawed his Lamassu into pieces. To transport them to Paris, the great bulls of Khorsabad were sliced into manageable blocks, to be reassembled later in the Louvre. Layard, more purist (or perhaps just more stubborn), insisted on moving his bulls whole.

The Qurnah Disaster

Not all the bulls made it to Europe. The Tigris River is treacherous, and in the mid-19th century, it was plagued by piracy and unpredictable currents.

In 1855, a massive convoy of rafts (known as keleks, made of wood supported by inflated sheepskins) set off from Mosul. They carried hundreds of crates of reliefs and statues from Khorsabad and Kuyunjik, destined for the Louvre. It was the "Elgin Marbles" of Assyria.

Near the town of Al-Qurnah, where the Tigris meets the Euphrates, disaster struck. Local tribes, in rebellion against the Ottoman governor, attacked the convoy. In the chaos, or perhaps due to the treacherous currents, the rafts capsized.

Several colossal Lamassu and winged genies, along with hundreds of cases of exquisite bas-reliefs, sank into the silt of the riverbed. They are still there today. Somewhere beneath the muddy waters of southern Iraq lies a lost fleet of Assyrian gods, buried not by time, but by the folly of extraction. The "Qurnah Disaster" remains one of the greatest losses in archaeological history, a reminder that the journey from the ancient world to the modern museum is fraught with peril.

Part III: The Dark Age (2014–2017)

Fast forward to June 2014. The black flags of the Islamic State swept across the Nineveh Plains. Mosul, the second-largest city in Iraq, fell in days.

For the archaeologists of Iraq, this was the beginning of a nightmare. The ideology of ISIS (Daesh) viewed the pre-Islamic heritage of Mesopotamia as Jahiliyyah—the age of ignorance. To them, the Lamassu were idols, affronts to the unity of God that had to be destroyed.

In February 2015, ISIS released a video that shocked the world. It showed men in the Mosul Museum taking sledgehammers to statues. We watched, helpless, as a bearded militant took a power drill to the face of a granite Lamassu at the Nergal Gate of Nineveh. The dust of 3,000 years puffed into the air as the face of the king was obliterated.

But the destruction was not just performative; it was cynical. While they destroyed statues on camera for propaganda, they were quietly looting others to sell on the black market.

The Secret of Nebi Yunus

The most dramatic story of this era centers on the Shrine of Nebi Yunus.

Nebi Yunus (Prophet Jonah) is a hill on the eastern side of Mosul. For centuries, a mosque stood atop it, believed to house the tomb of Jonah, the biblical prophet swallowed by the whale. It was a site sacred to both Muslims and Christians.

In July 2014, ISIS rigged the mosque with explosives and blew it up. The explosion leveled the shrine, leaving a mound of rubble. But ISIS did not stop there. They knew that beneath the mosque lay the ruins of an older palace—the Military Palace of Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BCE).

Under the cover of night, ISIS recruited locals to dig tunnels into the hill. They were looking for artifacts to loot—cylinder seals, gold, pottery. They dug a honeycomb of unstable tunnels, shored up with wood and corrugated iron, deep into the heart of the Assyrian mound.

They found the palace. And in the darkness of the tunnels, they found the guardians.

The Miracle of Khorsabad

While Nineveh burned, a quieter drama was unfolding in Khorsabad, the site where Botta had dug nearly two centuries prior.

In 1992, Iraqi archaeologists had uncovered a massive Lamassu near the village. It was pristine, its body intact, though its head had been stolen by looters in 1995 (the head was later recovered and is now in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad). To protect the body, the Iraqi authorities reburied it in the 1990s.

When ISIS approached Khorsabad in 2014, the local villagers—the descendants of the men who had worked for Botta—knew the location of the buried bull. A legend persists that the villagers, knowing the terrorists were coming, heaped more earth and debris over the site, effectively hiding the god from the iconoclasts. ISIS ravaged the surface ruins, but they missed the prize beneath their feet.

The curse of the Lamassu, it seemed, had evolved. It was no longer protecting the king from demons; the people were protecting the Lamassu from the new demons.

Part IV: The Resurrection

Mosul was liberated in 2017. The battle was brutal, leaving the Old City in ruins. But as the smoke cleared, the archaeologists returned.

At Nebi Yunus, the scene was precarious. The tunnels dug by ISIS were on the verge of collapse. Entering them was a risk to life and limb. But when archaeologists from the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH), supported by teams from Heidelberg University, crawled into the gloom, they turned on their flashlights and gasped.

There, carved into the limestone walls of the tunnels, were the reliefs of Esarhaddon. And guarding the entrance to the throne room was a Lamassu of unprecedented size.

This was the "Mosul Colossus" of the headlines.

It stands—or rather, sits in the earth—at nearly 6 meters tall. To put that in perspective, the famous Lamassu in the British Museum are about 3.5 to 4 meters tall. This new find dwarfed them. It was a monster among monsters.

The discovery fundamentally changed our understanding of the site. We now knew that Esarhaddon’s palace was not just a military garrison, but a royal seat of immense splendor. The Lamassu was unfinished in parts, offering a rare glimpse into the sculptor's process—the rough chisel marks showing how the form was liberated from the block.

The Khorsabad Excavation (2023)

Meanwhile, back at Khorsabad, a French-Iraqi team led by the indefatigable Pascal Butterlin returned in October 2023 to check on the buried bull.

When they carefully removed the earth that had shielded it for 30 years (and from ISIS), they found it remarkably intact. The alabaster was white and gleaming. The feathers of the wings were crisp, the muscles of the bull taut.

"I have never unearthed anything this big in my life," Butterlin told reporters. It weighed 18 tons. The fact that it had survived the chaotic 1990s, the 2003 invasion, the looting that followed, and the ISIS occupation was nothing short of a miracle.

Technology Meets Antiquity

The resurrection of these Colossi is not just about shovels and brushes. It is about lasers and code.

Because the tunnels at Nebi Yunus are too dangerous to open to the public, and too unstable to move the artifacts easily, archaeologists have turned to photogrammetry. Using thousands of high-resolution photos taken in the cramped dark, they have created 3D "point clouds"—digital twins of the tunnels.

One such project, "Rekrei" (formerly Project Mosul), crowdsourced photos from tourists who had visited the Mosul Museum before its destruction to create 3D models of the lost statues. In London’s Trafalgar Square, the artist Michael Rakowitz created a full-scale replica of the destroyed Lamassu using 10,000 empty cans of Iraqi date syrup—a poetic commentary on the extraction of resources and the destruction of culture.

But in Mosul, the work is more visceral. The "Revive the Spirit of Mosul" initiative, led by UNESCO, is training a new generation of Iraqi stonemasons. They are learning to work with "Mosul marble," the local alabaster that Sargon and Sennacherib used. They are rebuilding the Al-Nouri mosque and the churches of the Old City. And they are stabilizing the Colossus.

The Future of the Colossus

The question now faces the Iraqi authorities: What do to with the Mosul Colossus?

Do you cut it up, like Botta did, to move it to a museum? Do you leave it in the tunnels, forever in the dark? Or do you excavate the entire mound, removing the ruins of the mosque to reveal the palace below?

It is a dilemma of stratigraphy. To reveal the Assyrian past is to destroy the Islamic layer above it. In a city as religiously diverse and scarred as Mosul, this is political dynamite.

For now, the Colossus waits. It has been reburied or secured, protected by sensors and guards. The head of the Khorsabad bull sits in Baghdad, while its body lies in the north—a symbol of a fractured country slowly knitting itself back together.

Conclusion: The Fifth Leg

There is a profound irony in the story of the Lamassu. These creatures were built to project strength, to terrify, to say "Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair." But today, their power comes not from their intimidation, but from their vulnerability.

We do not look at the Mosul Colossus and feel fear. We feel a desperate protectiveness. We see the scars of the jackhammers and the cuts of the saws, and we see our own shared history.

When the Assyrian sculptors carved that fifth leg, they intended to create an illusion of movement, to make the stone walk. They succeeded more than they could have imagined. These bulls have walked through fire, through water, through time. They have walked from the palaces of tyrants to the halls of the Louvre, and from the darkness of ISIS tunnels back into the light of the Iraqi sun.

The King is dead. The Empire is dust. But the Bull still stands. And as long as the people of Mosul are willing to hide it, protect it, and unearth it, it always will.

Reference:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8QNfoWK-a4

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamassu

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/lamassu

- https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/ancient-near-east1/assyrian/a/lamassu-backstory

- https://smarthistory.org/lamassu-from-the-citadel-of-sargon-ii/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mseeiHn-iA

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/sparking-imagination-rediscovery-assyrias-great-lost-city

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289087530_Space_Sound_and_Light_Toward_a_Sensory_Experience_of_Ancient_Monumental_Architecture

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/digital-preservation-syria/

- https://qz.com/697225/european-researchers-used-3d-modeling-and-instagram-to-recreate-a-museum-destroyed-by-the-islamic-state