A Sunken Treasure Trove: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Antikythera Shipwreck

In the vast, azure expanse of the Aegean Sea, nestled between the Greek mainland and the island of Crete, lies the small, windswept island of Antikythera. For centuries, its rugged cliffs and treacherous waters guarded a secret of immense historical and technological importance. It was here, in the year 1900, that a chance discovery would set in motion a century-long saga of archaeological exploration, revealing the richest ancient shipwreck ever found and an object that would rewrite the history of technology. This is the story of the Antikythera shipwreck, a tale of heroic divers, visionary explorers, and cutting-edge science, all converging on a single, fateful spot on the seabed.

A Chance Discovery in the Deep

The story of the Antikythera shipwreck begins not with archaeologists, but with a team of Greek sponge divers from the island of Symi. Around Easter in 1900, Captain Dimitrios Kondos and his crew were en route to their fishing grounds off the coast of North Africa when a violent storm forced them to take shelter by Antikythera. While waiting for the tempest to subside, one of the divers, Elias Stadiatis, decided to explore the local waters in his standard diving dress of the era—a canvas suit and a heavy copper helmet.

Descending to a depth of 45 meters (about 148 feet), Stadiatis was confronted with a startling and macabre sight. He frantically signaled to be pulled back to the surface, where he described a nightmarish scene of "rotting corpses and horses" strewn across the seafloor. Kondos, initially suspecting his diver was suffering from nitrogen narcosis, a common affliction at such depths that can cause hallucinations, decided to descend himself to verify the claim. He soon resurfaced, not with a tale of horror, but with a tangible piece of history: the bronze arm of a statue. The "rotting corpses" Stadiatis had seen were, in fact, the scattered remains of magnificent bronze and marble statues.

Realizing the magnitude of their find, Kondos and his crew reported their discovery to the authorities in Athens. The Greek government, recognizing the potential significance of the wreck, acted swiftly. Hellenic Navy vessels were dispatched to support a salvage effort that would last from November 1900 through the summer of 1901. This operation, undertaken by the sponge divers with the assistance of the Royal Hellenic Navy and the Greek Ministry of Education, is now considered the first major underwater archaeological expedition in history.

The Perils and Triumphs of the First Salvage

The conditions for the early salvage operation were incredibly challenging. The divers were working at the very limits of what was possible with the technology of the time. They had only a single diving suit to share, and each man could only spend a few minutes at the dangerous depth twice a day. The work was perilous, a constant battle against the crushing pressure and the ever-present danger of decompression sickness, or "the bends." The toll was heavy: the expedition was ultimately cut short after the death of one diver, Giorgos Kritikos, and the permanent paralysis of two others.

Despite the immense risks, the haul of artifacts was staggering. By the time the operation concluded, the divers had brought to the surface an astonishing collection of treasures that would fill galleries at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. The recovered items included a stunning bronze statue of a young man, now famously known as the Youth of Antikythera (or Antikythera Ephebe), dated to around 340 BC. They also salvaged 36 marble sculptures, including depictions of mythological figures like Hercules, Odysseus, Diomedes, Hermes, and Apollo. Three life-size marble horses were recovered, though a fourth was tragically dropped during the recovery and lost back to the depths.

The cargo was not limited to fine art. The divers retrieved ornate glassware, beautiful ceramics, gold jewelry, and silver and bronze coins. Elements of the ship itself were also recovered, including lead scupper pipes and hull sheeting, as well as a set of lead sounding weights, which are the only examples of their kind ever discovered on an ancient shipwreck in the Aegean.

The Antikythera Mechanism: A Revelation in a Corroded Lump

Among the treasures brought to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens was a heavily corroded and unassuming lump of bronze and wood. It was initially overlooked amidst the more spectacular statues and was set aside in storage. It sat there for two years, until May 17, 1902, when a perceptive archaeologist named Valerios Stais was studying the finds. He noticed that the corroded lump had split open, revealing something extraordinary within: a complex assembly of gear wheels with legible Greek inscriptions.

This object, which came to be known as the Antikythera Mechanism, was unlike anything ever seen from the ancient world. It was so technologically advanced that many scholars initially refused to believe it could have come from the same wreck, deeming it an anachronism. The device, originally housed in a wooden case roughly the size of a shoebox, was a sophisticated, hand-powered astronomical calculator. It is now widely regarded as the world's oldest known analog computer.

Decades of intense research, including the use of advanced X-ray tomography and high-resolution scanning, have revealed the breathtaking complexity of the Mechanism. It consisted of at least 37 meshing bronze gears that could, with the turn of a hand-crank, model the movements of the Sun and the Moon through the zodiac. It could predict solar and lunar eclipses with remarkable accuracy and even track the four-year cycle of the ancient Olympic Games. The device incorporated sophisticated astronomical theories of its day, including a model for the irregular orbit of the Moon, a feat that would not be matched by any known technology for over a millennium. The discovery of the Antikythera Mechanism single-handedly rewrote our understanding of the technological capabilities of the ancient Greeks, proving they were far more advanced than previously imagined.

The Intervening Years: A Long Silence

After the initial heroic but tragic salvage effort ended in 1901 and the subsequent discovery of the Mechanism's importance, the Antikythera wreck lay largely undisturbed on the seabed for over half a century. The site was too deep and the conditions too hazardous for the diving technology available for most of the early 20th century. While the artifacts in Athens were studied, the wreck itself remained a silent testament to a forgotten voyage.

The silence was briefly broken in 1953 when the legendary French naval officer and undersea explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau, accompanied by MIT professor Harold "Doc" Edgerton, paid a short visit to the site. Edgerton was testing a new underwater strobe light, and their three-day dive was enough to convince Cousteau of the site's immense potential. However, it would be another 23 years before he could mount a full-scale expedition.

Cousteau's Return: "Diving for Roman Plunder"

In the summer and autumn of 1976, at the invitation of the Greek government, Jacques Cousteau returned to Antikythera with his famous research vessel, the Calypso. This new expedition, conducted under the supervision of Greek archaeologist Dr. Lazaros Kolonas, marked the second major phase of exploration of the wreck. The expedition was documented in an episode of Cousteau's television series, aptly titled "Diving for Roman Plunder."

Cousteau's team employed the latest technology of the era, including a suction dredge to carefully remove sediment that had accumulated over the wreck for more than two millennia. This allowed them to uncover and recover nearly 300 additional artifacts. The finds included more ceramic jars, bronze and silver coins, pieces of bronze and marble sculptures, bronze statuettes, and gold jewelry.

Crucially, the coins recovered during the 1976 expedition helped to more precisely date the shipwreck. Analysis showed they were minted between 76 and 67 BC, suggesting the ship could not have sunk before the latter date. This new evidence effectively debunked a long-standing theory that the ship might have been carrying loot from the Roman General Sulla's sack of Athens in 86 BC. The dating of the coins pointed to a later, though no less significant, voyage.

Perhaps most poignantly, Cousteau's team also recovered human skeletal remains belonging to at least four individuals. For the first time since the wreck was discovered, there was direct evidence of the people who had sailed on this ill-fated voyage. However, the scientific techniques of the time were limited in what they could reveal about these ancient mariners.

The 1976 expedition brought the Antikythera shipwreck back into the global spotlight, captivating a new generation with its story of sunken treasure and ancient mysteries. Yet, even after Cousteau's work, it was clear that the wreck still held many more secrets. Following this expedition, another long period of silence fell over the site, with no further dives taking place for more than three decades.

The Return to Antikythera: A New Era of Exploration

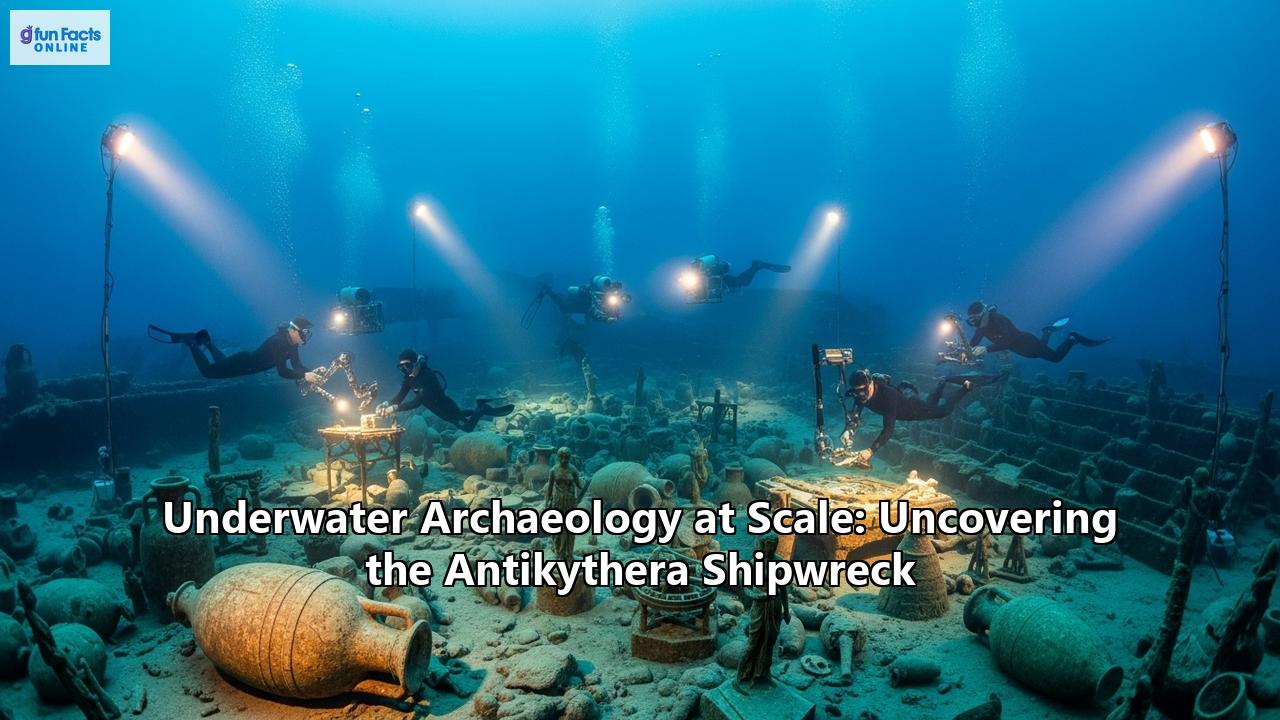

The dawn of the 21st century brought with it a revolution in underwater technology, opening up new possibilities for exploring the deep sea with unprecedented precision and safety. In 2012, a new international and interdisciplinary project, aptly named "Return to Antikythera," was launched, heralding a new era of scientific investigation at the famous wreck site. This ambitious undertaking has been a collaboration between the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), and, since 2021, the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece (ESAG) at the University of Geneva.

The project has been led by a team of renowned marine archaeologists, including Brendan Foley (formerly of WHOI and now at Lund University), Theotokis Theodoulou of the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, and Lorenz Baumer of the University of Geneva. The overarching goal of the new project is to conduct the first-ever systematic, scientific excavation of the shipwreck, employing a suite of advanced technologies to formulate a much clearer and more detailed understanding of the ship, its route, its cargo, and the circumstances of its sinking.

The Technological Arsenal

The "Return to Antikythera" project has been defined by its use of cutting-edge technology, which has allowed researchers to overcome the challenges of depth and harsh conditions that so hampered previous efforts.

- Robotic Mapping: Before any excavation began, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) were deployed to create highly detailed, 3D maps of the wreck site and the surrounding seabed. These robotic vehicles, equipped with stereocameras and sonar, could survey large areas with incredible precision, providing the archaeologists with a comprehensive blueprint of the site. This allowed them to identify areas of interest and plan their excavations with surgical accuracy.

- Advanced Diving Technology: The depth of the wreck, at around 55 meters (180 feet), places it at the edge of what is safe for conventional scuba diving. To overcome this, the modern expeditions have utilized mixed-gas closed-circuit rebreathers. Unlike traditional scuba gear, which releases exhaled air into the water, rebreathers recycle the diver's air, scrubbing out carbon dioxide and adding precise amounts of oxygen. This allows for much longer and deeper dives—up to three hours at a time—greatly increasing the amount of productive work that can be done on the bottom.

- The Exosuit: In 2014, the team brought in a truly futuristic piece of equipment: the Exosuit. This atmospheric diving system is essentially a wearable submarine, a one-of-a-kind, $1.5 million diving suit that looks like something out of a science fiction film. Made of an aluminum alloy, the Exosuit allows a single diver to descend to depths of up to 1,000 feet while remaining at normal sea-level air pressure inside the suit. This completely eliminates the risk of decompression sickness and the need for long, dangerous decompression stops on the way back to the surface. Equipped with thrusters, powerful grippers, and HD cameras, the Exosuit provides a revolutionary platform for deep-water archaeological work.

A Cascade of New Discoveries

Armed with this advanced technology, the "Return to Antikythera" team has made a series of spectacular discoveries, adding rich new chapters to the story of the shipwreck.

The project began in 2012 with a preliminary survey that relocated the main wreck and, intriguingly, identified a second ancient shipwreck a few hundred meters to the south. The years that followed brought a steady stream of finds. The 2015 season yielded over 50 artifacts, including a bronze armrest that may have belonged to a throne, the remains of a bone flute, fine glassware, and a pawn from an ancient board game, offering intimate glimpses into life aboard the ship.

One of the most significant finds came in 2016 with the discovery of a human skeleton, buried under a thick layer of sediment and broken pottery. Nicknamed "Pamphilos," this was the first skeleton to be recovered from an ancient shipwreck in the age of DNA analysis. The find included a skull with teeth, arm and leg bones, and ribs. This discovery offered the tantalizing possibility of extracting ancient DNA to learn about the victim's ethnicity and geographic origin.

The discoveries have continued in more recent years. In 2022, the team, now under the coordination of the University of Geneva, lifted several massive boulders that had been partially covering the wreck, giving them access to a previously unexplored area. This led to the discovery of a magnificent, larger-than-life-size marble head of a bearded man, identified as a depiction of Hercules of the Farnese type. It is believed that this head belongs to the headless statue of Hercules that was recovered by the sponge divers back in 1900. In the same season, two human teeth were also found, offering further opportunities for genetic and isotopic analysis to shed light on the origins and diet of the people on board.

The most recent expeditions in 2024 and 2025 have yielded even more groundbreaking finds. The team successfully recovered a significant portion of the ship's hull, with several planks and frames still attached. This has provided definitive confirmation that the ship was built using the "shell-first" method, a common technique in the Mediterranean between the 4th and 1st centuries BC, where the outer hull was constructed before the internal ribs were installed. Initial analysis of the wood has identified it as elm and oak.

The 2024 season also confirmed the presence of a second wooden vessel at the site 200 meters away from the main wreck. Initial analysis suggests that this second ship dates from around the same period, raising fascinating new questions. Was this a companion vessel that sank in the same storm? Or was it an unrelated tragedy that occurred at a different time? Further investigation is needed to unravel this new mystery.

Weaving Together the Story of a Lost Voyage

Thanks to more than a century of exploration and the application of ever-advancing technology, a clearer picture of the Antikythera ship and its final, tragic voyage is beginning to emerge.

The ship itself was a massive vessel for its time, a large merchant ship, possibly a grain carrier, estimated to have been up to 50 meters in length. The isotopic analysis of lead objects from the ship, such as the hull sheathing and anchor components, aims to pinpoint the origin of the lead, which could in turn reveal the ship's home port. The cargo itself tells a story of immense wealth and luxury. The collection of fine art, including both original Greek masterpieces from the 4th century BC and later Hellenistic copies, suggests the ship was carrying a specially commissioned collection for a wealthy Roman patron. Some have speculated that the ship was sailing from a major port in the Eastern Mediterranean, such as Pergamon or Ephesus, and was destined for a port in Italy, possibly to furnish the villa of a powerful Roman aristocrat.

The personal effects found on board—the jewelry, the gaming pieces, the musical instruments, the fine tableware—paint a picture of the people on the ship. They were not just a crew of sailors, but likely included wealthy passengers as well. The human remains, from the four skeletons found by Cousteau to "Pamphilos" and the more recently discovered teeth, are the most direct link we have to these individuals. Ongoing DNA and isotopic analysis may soon tell us more about who they were, where they came from, and what their lives were like.

The discovery of a potential second shipwreck adds another layer of complexity and intrigue to the story. Was this a small fleet of ships traveling together, perhaps for safety, that was caught in the same ferocious storm that drove the main vessel onto the rocks of Antikythera? The answer to this question may lie buried in the sediment, waiting for the next phase of exploration.

A Legacy of Discovery and Innovation

The Antikythera shipwreck is more than just a collection of priceless artifacts. It is a time capsule that has preserved a unique moment from the ancient world, offering unparalleled insights into art, trade, technology, and daily life in the 1st century BC. The discovery of the wreck in 1900 gave birth to the very field of underwater archaeology, and for over 120 years, it has been a crucible for innovation, pushing the boundaries of what is possible in the exploration of the deep.

From the heroic but ill-equipped sponge divers of 1900 to the "iron man" Exosuit of the 21st century, the story of the Antikythera shipwreck is a testament to the enduring human quest for knowledge and discovery. Each new expedition builds on the work of those who came before, and with each new find, the wreck offers up a few more of its long-held secrets. The "Return to Antikythera" project is ongoing, and as archaeologists continue to meticulously excavate the site, there is no telling what other wonders lie waiting in the silent depths off this remote Greek island. The adventure, as it has been for more than a century, is far from over.

Reference:

- https://www.google.com/search?q=time+in+Attiki,+GR

- https://www.unige.ch/medias/en/2025/anticythere-une-portion-du-navire-antique-remonte-la-surface

- https://www.greece-is.com/mapping-the-antikythera-wreck-in-3d/

- https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/antikythera-shipwreck-excavation/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=owVfI4p0zgs

- https://archaeologymag.com/2024/07/secrets-from-ancient-antikythera-shipwreck/

- https://www.egconf.com/videos/brendan-foley-marine-archaeologist-eg9

- https://greekreporter.com/2024/07/01/second-ancient-shipwreck-discovered-antikythera-greece/

- https://archaeology.org/news/2025/07/11/new-discoveries-from-famed-antikythera-shipwreck/

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/antikythera-shipwreck-greece-divers-find-second-wreck-new-treasures/

- https://www.whoi.edu/ocean-learning-hub/ocean-topics/ocean-human-lives/underwater-archaeology/antikythera-shipwreck/

- https://antikythera.org.gr/

- https://athenscentre.gr/return-to-the-antikythera-shipwreck-the-exosuits-first-mission/

- https://antikythera.org.gr/participants/team/2012-2017/

- https://kytherianassociation.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Return-to-the-Antikythera-Shipwreck.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antikythera_wreck

- https://nuttersworld.com/roman-era-shipwrecks-mediterranean/antikythera-shipwreck/

- https://antikythera.org.gr/participants/special-thanks/hublot/

- https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/science/swiss-researchers-uncover-second-ship-in-antikythera-shipwreck-investigation/82471105

- https://www.esag.swiss/return-to-antikythera-2022/

- https://www.sydney.edu.au/engineering/news-and-events/news/2016/09/29/diving-for-dna-2000-year-old-skeleton-discovered-on-antikythera.html

- https://www.sci.news/archaeology/science-antikythera-shipwreck-new-artifacts-03279.html

- https://www.livescience.com/46339-photos-antikythera-shipwreck-diving-mission.html

- https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/archaeology-today/archaeologists-to-probe-antikythera-shipwreck-with-hi-tech-diving-suit/

- https://www.livescience.com/47860-exosuit-mission-antikythera-shipwreck.html

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/09/160919160803.htm

- https://www.livescience.com/antikythera-mechanism-shipwreck-new-artifacts

- https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/archaeology-today/two-shipwrecks-for-the-price-of-one/