A Realm of Perpetual Night: The Astonishing Life of the Hadal Zone

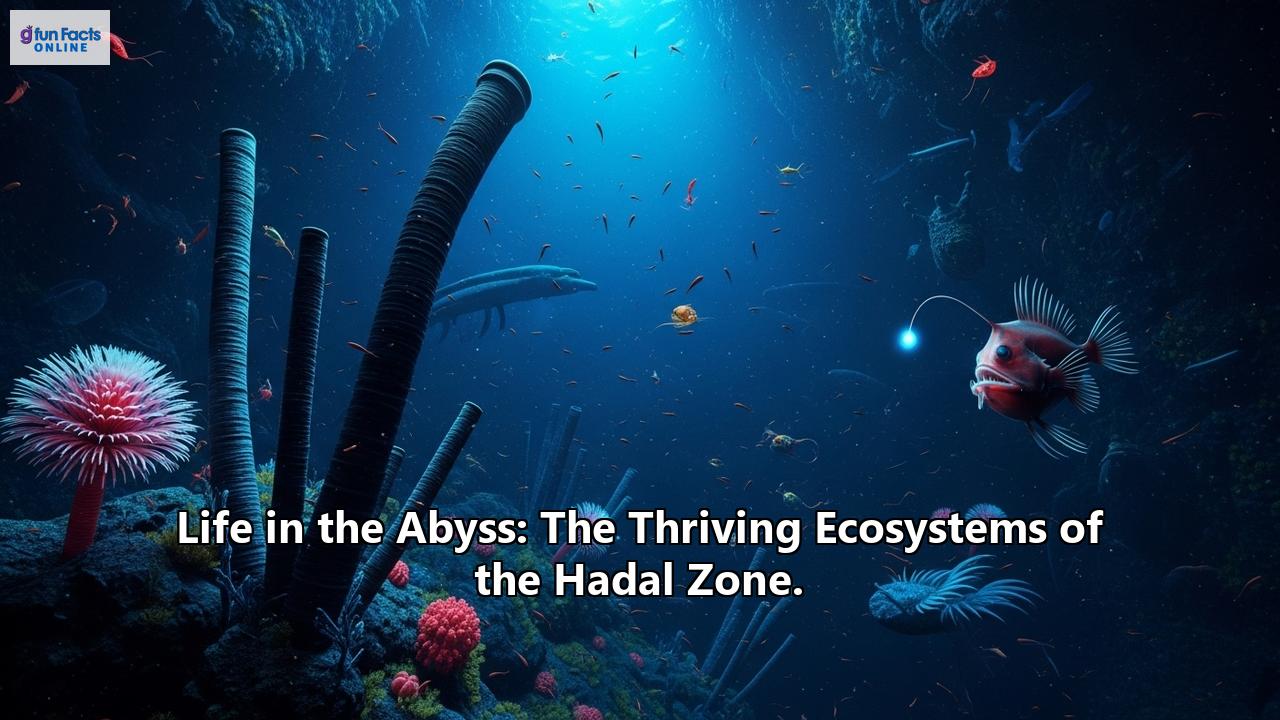

Plunge deep into the ocean, far beyond the reach of the sun's rays, and you will discover a world of crushing pressure and profound darkness. This is the hadal zone, the deepest and most enigmatic part of our planet's oceans, a realm once thought to be devoid of life. Named after Hades, the Greek god of the underworld, this region extends from 6,000 meters (about 20,000 feet) to the very bottom of the ocean's deepest trenches, some of which plummet to nearly 11,000 meters (about 36,000 feet). It is a world of extremes, yet against all odds, it is home to a surprisingly vibrant and unique ecosystem.

The hadal zone is not a vast, uniform abyss but is instead comprised of at least 47 geographically disjunct trenches, troughs, and basins that punctuate the abyssal plains. These V-shaped depressions are primarily found around the Pacific Rim, formed by the dramatic process of one tectonic plate subducting beneath another. The conditions here are almost beyond comprehension. The pressure can exceed 1,100 standard atmospheres, equivalent to the weight of a large truck balanced on your fingertip. Temperatures hover just above freezing, and there is a complete and utter absence of sunlight. These factors, combined with the geographical isolation of each trench, have created a series of unique habitats that have driven the evolution of extraordinary life forms.

Surviving the Abyss: A Masterclass in Adaptation

The creatures that inhabit the hadal zone are a testament to the tenacity of life, having evolved a remarkable suite of adaptations to thrive in such an unforgiving environment. To counteract the immense pressure that would crush most organisms, many hadal species have developed specialized physiological and biochemical mechanisms. A key adaptation is the production of a chemical called trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), which helps to stabilize proteins and other critical molecules within their cells. This adaptation is so crucial that it is believed to set the depth limit for fish; at a certain point, the concentration of TMAO required becomes so high that it is no longer physiologically possible to produce, suggesting a theoretical maximum depth for vertebrate fish of around 8,000 to 8,500 meters.

The absence of a gas-filled swim bladder is another common trait among hadal fish, as such a structure would collapse under the extreme pressure. Many deep-sea fish have also evolved bodies that are more gelatinous and have lower bone density. For instance, the hadal snailfish, one of the deepest-living fish ever recorded, has an almost translucent appearance and a cartilaginous skeleton, allowing it to withstand the immense pressure.

In the perpetual darkness, eyesight as we know it is of little use. Consequently, many hadal creatures have lost their photoreceptor genes and are blind. Instead, they have developed other heightened senses to navigate and find food. Some have acute chemoreceptor organs to detect the scent of falling carcasses, while others possess tactile appendages to feel their way through the dark. Bioluminescence, the ability to produce light, is another common adaptation, used for communication, attracting prey, or deterring predators in the inky blackness.

A Food Web Fueled by Darkness

With no sunlight to support photosynthesis, the foundation of the hadal food web is fundamentally different from that of shallower ecosystems. Life in the abyss is largely dependent on a "rain" of organic material from the upper layers of the ocean. This "marine snow," consisting of dead plankton, fecal matter, and other fine organic particles, slowly drifts down to the seafloor, providing a steady, albeit meager, source of nutrition for many organisms.

Larger windfalls, such as the carcasses of whales, fish, and squid, also sink to the hadal depths, creating ephemeral but bountiful feasts for scavengers. Hadal amphipods, a type of crustacean, are particularly adept at locating and consuming these large food falls. These creatures, which can exhibit "gigantism" and grow to surprisingly large sizes compared to their shallow-water relatives, are considered dominant scavengers in the hadal food web.

Beyond this reliance on falling detritus, some hadal ecosystems are fueled by a process called chemosynthesis. At hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, bacteria and other microorganisms harness chemical energy from compounds like hydrogen sulfide and methane that are released from the Earth's crust. These chemosynthetic microbes form the base of a unique food web, supporting a diverse community of organisms, including giant tube worms, bivalves, and sea anemones.

The Frontiers of Exploration

For a long time, the hadal zone remained one of the most unexplored and misunderstood habitats on Earth. The extreme conditions pose immense technological challenges for exploration. However, with advancements in marine technology, our understanding of this deep-sea realm is rapidly expanding.

The development of sophisticated underwater vehicles, such as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), has allowed scientists to explore these depths in unprecedented detail. These vehicles can withstand the crushing pressure and navigate the complex terrain of the trenches, capturing high-definition video, collecting biological and geological samples, and mapping the seafloor.

These modern expeditions have revealed a surprising diversity and abundance of life. Far from being a desolate wasteland, the hadal zone is home to a wide range of organisms, including fish, sea cucumbers, bristle worms, bivalves, isopods, and sea anemones. In fact, recent research suggests that hadal trenches can be hotspots of biodiversity and biological activity, acting as funnels that concentrate organic matter from the surrounding abyssal plains.

Guardians of the Deep

The study of the hadal zone is not just about discovering new species and understanding the limits of life. These deep-sea ecosystems play a crucial role in the global carbon cycle, with trenches acting as significant carbon sinks that help regulate our planet's climate.

However, even these remote and seemingly pristine environments are not immune to human impacts. Researchers have found evidence of pollutants, including plastics, in the guts of hadal animals, a stark reminder of the far-reaching consequences of human activity.

As our ability to explore and exploit the deep sea grows, so too does the need for conservation. The hadal zone is a unique and fragile environment, and its inhabitants may hold the keys to new scientific discoveries and medical breakthroughs. Protecting this last great frontier is not just about preserving the strange and wonderful creatures of the abyss; it is about safeguarding the health of our entire planet. The thriving ecosystems of the hadal zone are a powerful symbol of life's resilience and a reminder that even in the most extreme corners of our world, there is still so much left to discover and protect.

Reference:

- https://www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/how-the-ocean-works/ocean-zones/hadal-zone/

- https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/okeanos/explorations/ex2102/features/hadalzone/hadalzone.html

- https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/79/4/1048/6576454

- https://ecomagazine.com/in-depth/extreme-adaptation-surviving-in-the-hadal-zone/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadal_zone

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/hadal-zone-conservation-guide

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.743663/full

- https://www.ysi.com/ysi-blog/water-blogged-blog/2024/05/exploring-the-deepest-region-of-the-oceans

- https://www.quora.com/How-do-animals-adapt-in-the-hadal-zone

- https://www.aanderaa.com/media/pdfs/mission-water-10-hadal-article.pdf

- https://en.as.com/latest_news/what-is-in-the-hadal-zone-the-deepest-part-of-the-ocean-n/

- https://evidencenetwork.ca/hadal-zone-what-is-flora-and-fauna/

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/hadal-zone/food-supply-to-the-trenches/CC8FEE5A5185115C5500F7F2B98B24C8

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8454626/

- https://library.fiveable.me/key-terms/college-bio/hadal-zone

- https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/deep-sea-wonders-marine-biology

- https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2020/10/02/food-webs-deep-ocean-trenches/